Peter Coyote’s Summer of Love

By ROB SIDON

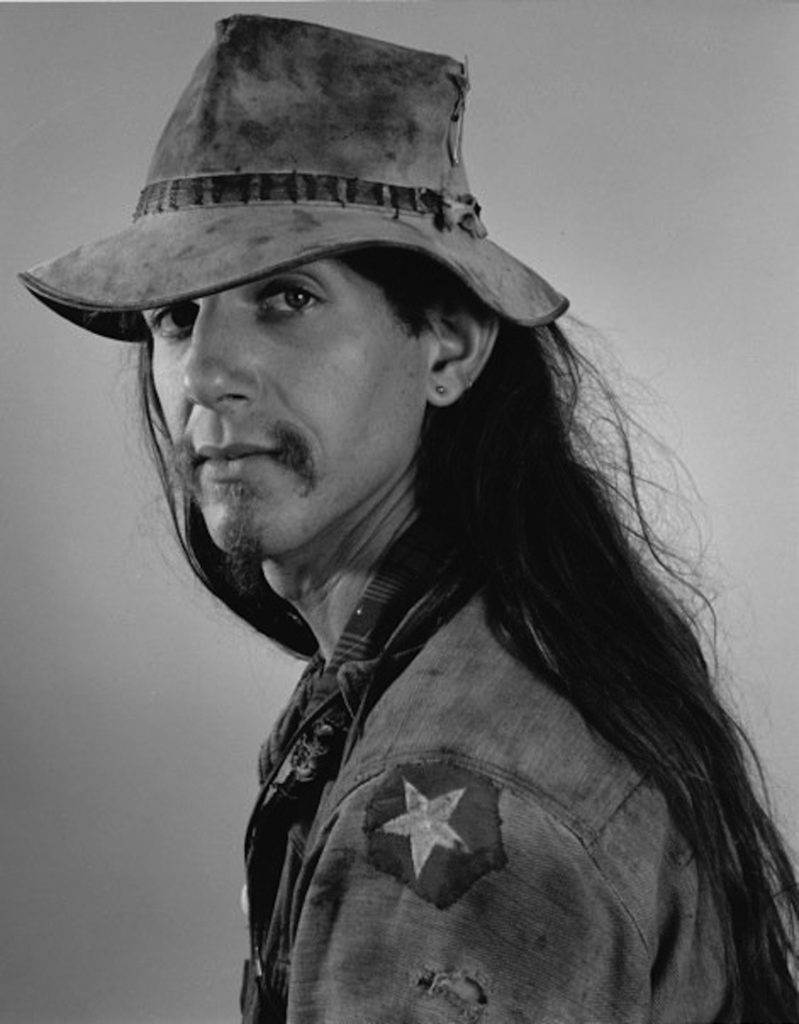

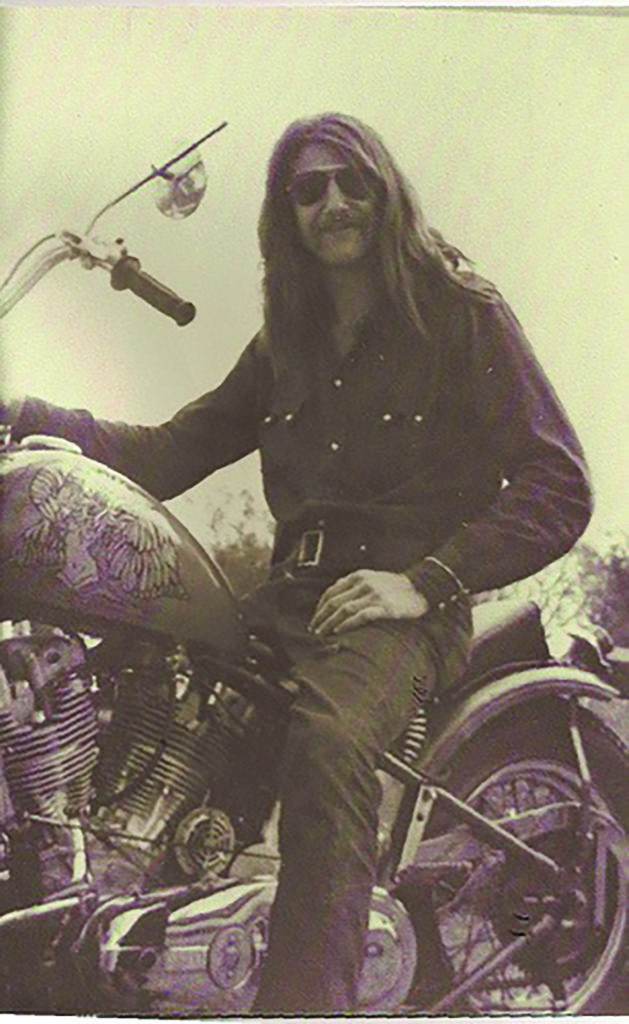

Peter Coyote was born Robert Peter Cohon in New York City in 1941 but later changed his name in response to his first peyote experience at Grinnell College in Iowa. In 1961 he received front-page coverage in the New York Times and a White House invitation for having helped stage one of the first student demonstrations in DC. With a knack for being at the right place at the right time, he quickly found himself after college at the epicenter of the nascent Haight-Ashbury scene as one of the founding members of the Diggers, an ultra-active communal anarchist improv group. Those in the know regard Peter Coyote as one of the utmost authorities on San Francisco’s 1960s counterculture because he was there making it happen.

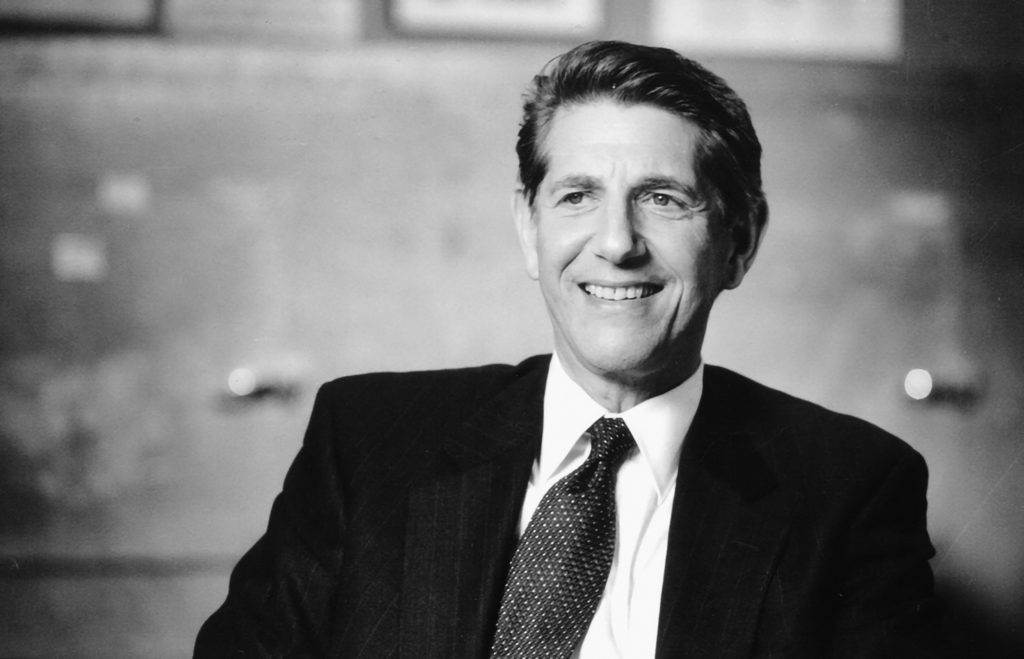

In the mid-seventies he discovered what would become a lifelong passion for Zen Buddhism, which in turn helped him kick a 12-year heroin addiction. During Governor Jerry Brown’s first term, Peter served as head of the California Commission of the Arts, where he raised the budget from $1 million to $16 million. Despite his deep-seated Digger attitudes of favoring anonymity and shunning notoriety, he enjoyed a late-in-life movie career, now having acted in over 120 films including E.T. the Extraterrestrial. His ambivalence toward Hollywood is reflected in his refusal to move to LA or even hire a publicist. By contrast, in Europe his indie authenticity has made him an A-lister who has graced the covers of many popular magazines.

Peter has been married and divorced twice and has two grown children. We spoke with him at his Sebastopol home on the summer solstice marking the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love.

Common Ground: The pretext for this interview is your 50-year perspective on the Summer of Love, but I wonder if you would try to condense your 75 years into an elevator speech?

Peter Coyote: Trying to be authentic. Trying to follow my honest curiosity and interests, which I consider to be more important than wealth or status.

We have the distinction of both being Grinnell College alumni. As you know, it’s a tiny, progressive school in the Iowa cornfields. It was there you received the inspiration to change your name.

We had sent to Texas for a box of peyote, and when it arrived we didn’t know what to do with it. We found out that there were Tameika Indians 30 miles away from Grinnell who used it, so we traded half the peyote for them to teach us how to take it. My friend Terry Bisson and I got very high, and at one point I said, “Hey, Terry, this is really strange but I feel like some kind of little wild dog. I don’t know what this is. I’ll see you later.” I spent the night dog-trotting through the cornfields, and in the morning as I was coming to, I was standing with all these little paw prints around me. I was so high I didn’t know if I had made them or if something else had made them.

A few years later, around 1966, I was living in Haight-Ashbury with a guy named Rolling Thunder, a powerful Shoshone Paiute Indian, and I told him that story. He said, “What are you going to do about it?” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “The universe opened its mind to you. You can consider it a hallucination and just remain a white man having an ordinary life, or you could plumb the significance and become a human being.” I took the name Peter Coyote as the first step to figuring out what this meant. The unintended immediate consequence was that nobody knew who Peter Coyote was. This left a wide field to redefine myself exempt from my family history, my school history—everything but my habits.

You had a challenging boyhood. Your dad was intense, while mom was submissive. What’s the story of your mom telling you “We have to be losers”?

My dad was a brilliant guy, a polymath who got into MIT at 15. He ran his own brokerage house and was president of the Hudson/Manhattan Railroad and the Phoenix Campbell Oil Company. Because of him I grew up in a wealthy household, but he was savagely angry and impatient. He was angry about the violence he received as a child and about the drowning of his twin brother when he was 12. He was angry about anti-Semitism. He’d break all the furniture.

Because I was a right-brained artistic thinker, he was afraid I was stupid and that the world would just eat me up. He felt it was his job to toughen me. I was 6 during my first boxing lesson when he knocked me out. He taught me wrestling by twisting and hurting me—excruciating—all the while giving me lectures about how to do this to other people. On some deep place he was threatening me and instituting his position as alpha dog.

One day after hurting me very badly, I went to Mom and said, “I hate Dad. I’m never going to wrestle again and I’m going to tell him.” She grabbed me and hissed, “You must never tell him that. If you hurt your dad’s feelings he will die.” She said, “Your dad has to win. You and I don’t have to. We are losers. We can lose.” Immediately, I felt the paralyzing double-bind: I was either going to lose my self-respect and do what my mother wanted, or I was going to lose my father, according to her scheme. It fucked me up. My pursuits became solitary, and I missed out on much that can be gained from athletics and being in the company of men and winning and losing and learning how to pick yourself up.

How did religion factor into your upbringing?

It didn’t. I was raised as a secular cultural Jew. I was bar-mitzvahed by my grandparents—my mother’s parents, who were orthodox—but religion didn’t factor into my upbringing. But I was always a spiritual person. My earliest memories are of seeing a robin so vividly that it seemed it was outlined in black ink to separate it from the rest of the environment. I worshiped nature and just knew that everything was alive and aware.

Perhaps one way to look at you is via the amalgam of your distinct Jewish ancestries. Your dad was Sephardic and your mom Ashkenazi.

Yeah, I think so. My father’s father was a Kazak, from Kazakhstan—tough people, eagle hunters, descendants of Genghis Khan. My dad’s side were warriors—colder, motivated, ambitious, more status conscious and “me first,” whereas my mother’s side was more open, warmhearted, familial, gregarious, purely intellectual, Leftist. For example, my mom’s cousin, Irving Adler, was the first man fired from the New York City School system for being a communist. Later he sued and won 28 years’ back pay.

In college you got national media attention as part of the “Grinnell 14” by protesting nukes in DC and getting invited to the White House. Can you tell the story?

Kennedy was considering resuming nuclear testing. You need to know that in the late fifties and early sixties, America was obsessed with atom bombs and Armageddon. We young people were afraid we’d die before becoming adults. In protest we quit going to classes and caucused and raised money to put together this platform supporting Kennedy’s peace race to resist atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. We bought two old cars to go to Washington, where we marched and fasted outside the White House. Meanwhile, these John Birchers just stood there eating fried chicken in front of us, being jerks.

Kennedy read about us on the front page of the New York Times and decided he liked us and invited us into the White House even though he was flying to Phoenix. He set up a meeting with McGeorge Bundy, who was his national security advisor. I was the designated spokesperson. When I first looked at Bundy I realized this guy didn’t give a shit about us or our cause or anything. We thought we were coming with information from the hinterland to help politicians make wiser decisions. We all had taken civics classes but I quickly realized those didn’t count for shit. I had one of my epiphanies—this was about raw power. The only way I was going to ever get this guy’s attention was to come back with an army. And a couple of years later I thought that the counterculture would be that army.

But anyway, back in 1961 we wrote letters and mimeographed those to every college in the United States and kept up this vigil outside the White House for about a year. Then in February 1963 came the first student demonstration in Washington, where 25,000 people showed up as a result of this inception. Tom Hayden called the Grinnell 14 the beginning of the student peace movement.

Right on.

Just being authentic, right? Just doing what we felt was right and saying “fuck the consequences.” We didn’t know anything—about where it was going or where it was going to be, but we know that we did something and moved the game a little bit—14 kids.

You still in touch with any of them?

Most of them. You can’t forget something like that.

After college you were admitted to the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop but did San Francisco beckon like Mecca? When did you come and what was it like?

No, I wish it was more principled but I was done with Iowa winters. I was also admitted to the SF State Writers Workshop, where Robert Duncan, one of my hero poets, was teaching. I came in the summer of 1964 and lived in a cheap apartment in a blue-collar neighborhood at Haight and Clayton. The Psychedelic Shop hadn’t started yet. Who knew?

One of your first activities was being part of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, right?

My first activity was going to school but that was disappointing. I got the acting bug at Grinnell and joined the San Francisco Actors Workshop for about a year before realizing I was in the wrong place, especially after I had discovered this little vibrant company called the San Francisco Mime Troupe run by Ronnie Davis, who was a fellow Marshall McLuhan fan. That was my introduction to radical politics and radical theater.

Let’s bore in about the Diggers, who were central to the whole scene. Can you explain the etymology of the Diggers and what that organization did?

In 17th century England, King Charles was building wool mills and needed the grass for his sheep so he stole the public commons, but the people resisted in civil war. A guy named Gerrard Winstanley was basically the first person to come out against private property, saying “property is theft” and along with Oliver Cromwell fought the king’s soldiers. They were called “the Diggers” because every morning they were seen burying their dead. That’s the origin.

The Diggers were created as an outgrowth of the Mime Troupe, with friends Emmett Grogan, Billy Landout, and Peter Berg. Emmett had come to the troupe from New York and was a great actor and a great rogue who challenged us by saying, “This is too easy—we’re onstage and in control. Why don’t we take our improvisatory skills to create events that really open people’s minds so they won’t know they’re in a theatrical event?”

We liked this idea of raising the mark. We decided we wanted to imagine a world where we could live authentically and make it real by acting it out. The first thing we did was imagine a world with free food. So we sent a bunch of our people to the farmers market, where they gave us food and we cooked it in people’s apartments. We put out a street flier that said, “Today, free food, 6 o’clock, Golden Gate Park, bring a bowl.”

It wasn’t about charity and feeding the poor. We wanted people to envision a world with free food, so we constructed a big yellow frame six feet by six feet called the Free Frame of Reference. To get the free food all you had to do was step through the frame. Then at the other end along with the food, we’d give a smaller frame of reference, about an inch by an inch, hanging on a shoelace that invited you to ask “What would the world be like if what you looked at was free?”

Didn’t you also run the Free Store? Where was it?

The early one was a hovel of shit piled up on Page Street but then we got a place on Cole and Carl—a beautiful space with glass windows. We made it into a real store where everything worked, such as furniture, bicycles, TVs, radios. Our thesis was “Why become an employee to make the money to become a consumer if we’ll give you the shit for free?” Also, the roles in the store were free. So if you came in and said, “Who’s the boss?” we’d say, “You are, what should we do?” So if you just dropped your jaw and looked stupid there was no sense blaming the pigs, or the system, or “the Man” because you’d just been offered a gig and dropped the ball. But if you said, “Well, I hate the way these shirts are laid out—let’s do this,” then we’d all do it. The free store was amazing theater.

One of my favorite stories was when I was managing and this older, heavyset black woman was stealing, or at least she thought she was. She was looking around, poking stuff so I went to her and whispered, “You can’t steal here.” She said, “I’m not stealing!” I said, “I know, but you think you’re stealing—but you can’t steal here because it’s a free store. You just take what you want.” She said, “It’s free?” I said yes. And she said, “Then get out of my face.” So I went away. Two days later she came back with a flat of day-old donuts.

She got it.

Laid them on the counter. She got it just like that.

What motivated you? What made you tick in that Digger era?

I always hated bullies and was raised without an ounce of racism and to believe in civil liberty, fairness, equity, racial justice, harmony—that’s what I was about. I wanted to call America on its markers. I had been embarrassed about what my country had done. So in my naiveté I felt fully empowered—that our time had come to take over. What we didn’t know was that America would kill its children before giving up power—at Kent State, at Jackson State. It would beat them bloody at the Chicago Democratic Convention. That was part of our maturity.

Weren’t you afraid of the draft?

No, because I had applied to be a conscientious objector when I was 18 in a thesis I would have written today about my honest beliefs. I said I could be a medic but wouldn’t carry a gun. They turned me down but I went to graduate school. After I quit graduate school they immediately called up, and I thought, “Fuck, I told the truth the first time and that didn’t work.” So I went to see the psychiatrist. I told him, “I’ll go but I keep what I catch.” He said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “War is rape, looting, pillaging, and I keep what I catch. [Long pause] And I’m homosexual.” I wasn’t homosexual but they still considered me psychologically unfit for service, which is true.

My favorite anti-draft activity was by a group called The Cockettes. They were a drag queen revue of hairy chested big motherfuckers in tutus and crinolines and beards who made no attempt to look like women. They would bring their van to the Oakland draft station and take kids into the van and give them a blowjob and take a Polaroid for them to give to the army psychiatrist. That was their draft resistance. They were my heroes.

[Laughs] That’s a terrific story. What was your relationship to the music at the time? The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin?

I knew them and they were okay, but I wasn’t particularly impressed. I grew up on jazz, blues, gospel, and folk music and appreciated skill over attitude. A lot of the rock-and-roll just seemed stupid but I kept my mouth shut. I went out with Janis. The Dead struck me as prep school kids but were a family much like the Diggers, so I respected them for a long time, but at the end of the day they wound up firing all their people and hiring a big merchandising company.

Didn’t you cross-pollinate with the Grateful Dead family?

We did but it was always a bit competitive. The Grateful Dead could come to our house and sit in on these really cutting-edge conversations and then the next day I might read about it in one of Jerry’s interviews. But when we went to them to try to get money for some of our events, they were sometimes a little snooty, like “What’s the matter, man, can’t you get your money trip together?” Well, no, we can’t because we don’t have anyone giving us $100,000 and $200,000 advances, thank you very much. They were like the rich kids and we were like hard scrabble dirt farmers but remember, all of those big parties with the Grateful Dead in the Panhandle were thrown by the Diggers. But that was before the record companies created two classes of people. You had one class with a lot of money and everybody else working for them.

What was it like dating Janis?

Janis and I were both dope users, so we had that. I felt bad for Janis because underneath everything, she was this little fucked-up girl from Port Arthur [Texas]. She was mesmerized and confused by all the publicity. I remember walking with her through New York and showing her a poster at the Fillmore East. I said, “What do you think about Mavis Staples?” She went on and on and on about how Mavis was her hero. I just said to her, “You got top billing.” So I’d take her around New York to see Jimmy Witherspoon and other great fucking singers who had been out there forever—just to try to keep her grounded. But it’s hard to resist when people are throwing dollars at you, saying you’re great. Black people are singing to make themselves feel better, or they’re singing to transform themselves. When you watch great black performers, they’re like a horse that’s holding power in reserve. White people are usually singing to show how bad they feel or how sensitive they are. Janis was always skinning herself alive in front of a crowd. Anyway, she was a friend of mine. We took a lot of dope together. I had a key to her house until she died but I wasn’t in awe of her music.

You were into weed in the fifties. Can you trace the arc of your drug use?

In 1958 when I was 17 I got turned on in Mexico and got busted at the border bringing back a lot of shit, but being a well-to-do white kid they paroled me to go to college and keep my nose clean. I smoked weed in college and had a friend who was snorting heroin once in a while there.

When did you first shoot it?

1966 or 1967. Emmett Grogan shot me up in Dennis Hopper’s house. Emmett’s wife walked in and turned right around and left him that day. We felt that drugs might put us into really free turf, but we didn’t understand the health cost.

You were addicted and contracted hepatitis. When did you quit?

I was addicted off and on for 12 years and had hep B and hep C. I only got rid of hep C two years ago. What got me to finally stop was after I’d gone to get my daughter, who was about 4 or 5 at the time and was being raised at the commune. That night I got high with a guy—only to wake up to find him dead across the table. I thought that if it had been me who died, my daughter would have become a ward of the state. That was intolerable.

You’ve been clean since 1974? What about psychedelics and stuff like that?

I did peyote for a long time in the sixties and for a while into the seventies. But I don’t do anything now. I don’t smoke weed or hash.

Do you have cautionary words—especially to young people who are experimenting with drugs?

Drugs are like flying to the Grand Canyon in a helicopter. It can be awesome but whatever drug trip you’re on, it ends. Because you flew out there in a helicopter that’s the only method you know. By meditating you can always just walk there. Eventually I got interested in a trip that wouldn’t end and didn’t require a helicopter.

Meeting Gary Snyder was a turning point?

It was. Gary was the first man I had ever met who was not unevenly developed. He did everything as well as he did anything. He took as much care of his family as he did with his poker tournaments and his garden and his health and his heart. I gradually came to understand that it had something to do with Buddhism. While I consider him a primary teacher, even to be on my rakusu, my ordination documentation, he is just my friend. My admiration for him is immense, but he always refused to be on any different status plane than I. He showed that while I may have been an idiot, I didn’t have to stay an idiot.

What’s your connection to Zen Buddhism and the SF Zen Center?

I first read about Zen in my early teens reading about Beat poets but had no idea what it was about. In 1974 I started keeping company with a woman that I later married who was a serious student at the San Francisco Zen Center. About 15 years ago I started studying with Lew Richmond, who was Suzuki Roshi’s assistant, and worked with Lew all the way through my priest ordination to what’s called transmission. This is where he transmits his authority to me and frees me from his authority. I could ordain my own line of priests if I wanted to. It’s just something that kept deepening and standing up to every rigorous examination, so I’m still there.

You had gigs at both the SF Commission of the Arts and the California Council of the Arts, where you increased the arts budget from $1 million to $16 million.

The city job was paid under CETA, the Comprehensive Education and Training Act, but in 1975 I was plucked by Governor Jerry Brown’s commission, where I dedicated every waking minute. It was an unpaid gig; I survived on $600 a month from CETA. I had started out being a nasty loudmouth taking no prisoners and little by little learned how Sacramento politics worked and became good at it, and the commission was a huge success. The National Endowment of the Arts copied some of our programs, as did The New York State Arts Council. But the day Jerry Brown was out of power, the new governor [George Deukmejian] cut the budget from 16 million back to 1 million dollars, and I thought, “I don’t have another decade to spend working on something that can be countermanded by fiat.” I threw myself deeper into Zen.

Was the arts commission a springboard to becoming a movie actor?

It was. I realized I had learned how to talk to conservatives, democrats, and won everybody’s respect. At our last finance committee hearing in Sacramento, three members, who were like the Mount Rushmore of Republicans, all put on hippie headbands to say goodbye to me. It was very touching. I realized I didn’t have to stay on the fringe of the counterculture and that I had to make a living. How was I going to get my daughter through college and buy a house for my wife? So I decided to give myself five years to try movie acting. I went back to the Magic Theater for two years and did nothing but back-to-back plays to shake out the rust. Then I got lucky, as I was at the right age when the current crop of leading ladies were approaching those margins where they began to look like day-old fruit and decided their best strategy was to appear with older men. So I got a lot of work.

You worked on over 120 movies, including with big directors like Spielberg and Polanski. Did you love it?

I liked acting and hated Hollywood. I hated how the business corrupted. I hated the preoccupation with status and how it affected friendships, but I had kids and an ex-wife to support, so I did it. As soon as I didn’t have to do it anymore, I stopped.

Seems you did it on your terms.

Nobody does it on their terms. I was ambivalent about being famous; it was contrary to all my Digger feelings so I didn’t do the things to be a star. I didn’t move to LA. I didn’t have a publicist. I didn’t go to screenings and openings. I tried to have a normal life for my kids but you pay a price for that. I have a number of A-list friends, and I might be at their house twice a week for dinner but that didn’t mean we would run around together in Hollywood or at film events.

I had a friend who was president of the jury at Cannes when I was flogging a film [The Lena Baker Story] about the first woman, a black woman, to be electrocuted in the State of Georgia by mistake. He insisted on having coffee together every morning because we were friends, and every morning he’d tell me a story about some great party he’d been to and the fantastic people he met and all the wonderful opportunities. And I just kept waiting for the shoe to drop, for him to say, “Wow, you ought to be there, Pete. Come with me tonight.” It just never happened. It’s hurtful.

I have five or six friends in this region who know Frances McDormand and her husband, Joel Coen of the Coen brothers. They tell me stories about lunches and dinners and how wonderful they are, and I am a huge fan of both of them but I’ve never been invited or introduced, so it’s hard to like Hollywood and the public world of status. If it had been me I would always be looking out for my friends, saying, “You got to be at that party—come on, we’re going together. I want you to meet these people. It’ll help you.”

As a kid I looked up in awe at Flower Power and the Summer of Love altruism and remember being disappointed when it all cratered in the seventies and eighties as people like Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman cashed out.

The reason I don’t care about the Summer of Love is that it was a marketing campaign of the Haight Independent Proprietors to create a nationwide brand for the Haight-Ashbury to sell hash pipes and Indian clothing and incense and all that crap. There was nothing radical except they were changing the content of the 18 inches of counter space in front of the cash register in the stores that their dads had. Now they sold paisley and psychedelic posters. The Diggers were consciously resisting that and trying to push the envelope further and deeper to make people think about what was really what.

I used to get indignant by contradictions when I was young. Now I’m not surprised. I just follow the money. Remember, the Diggers taught Abbie and Jerry everything. And they knew it. And they violated it. We taught them about anonymity, but Abbie went home and wrote Steal This Book and signed his name on it. Abbie and Jerry wanted to be leaders of the counterculture just like all those guys at the Democratic Convention. The Diggers didn’t have identifiable leaders and therefore couldn’t be infiltrated. We saw what happened to leaders from Robert Kennedy to Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcom X to Fred Hampton—the nail that sticks up gets pounded down. Jerry Rubin wanted to be a leader and he couldn’t because he was an idiot who went to Wall Street and then sold linoleum.

I don’t want to sound like those old communists I grew up around where the Marxists fought the Leninists, who fought the Trotskyists. Abbie had a huge ego that wanted to be recognized as the spokesman for our generation, and I disagreed with him but I also loved him. We were on the same side—not on Nixon’s side.

You’ve been around the block now and have a perspective on human nature. You’ve seen how young people—liberal or conservative—are mostly trying to find themselves, have a good life, and maybe get laid.

The big dividing point is what your idea of having a “good life” is. The Digger’s idea was to take everyone with us. When I went to New York in the sixties, I met Lou Reed and Leonard Cohen and Andy Warhol and that family. I looked at them and felt they’re all brilliant guys, but they’re just ambitious for themselves—they ain’t us. My idea of a good life is when everybody’s sharing the goodness. The Republicans in power now—they have a quite different idea of the good life. They just want to die with all their toys.

The Reagan administration decided they did not want another generation of educated, energetic, entitled students so they systematically began to define the counterculture as losers—dopers in bell-bottomed pants with clunky peace symbols who just fucked and stayed high. There was plenty of fucking and staying high but we worked our asses off and were serious. They defined us to the next generation as losers and sent that generation to get wealthy in the stock market and to buy BMWs.

But if you look at the changes that we brought in the United States culturally—the women’s moment, the environmental movement, alternative health practices, alternative spiritual practices, organic food. We didn’t win all our political battles, but we changed the culture.

It’s true. You don’t like the word activist. Why?

No, I hate it. It’s a word invented by my enemies. If you want to separate someone from the mass of humanity you put an -ist after the label: Communist. Socialist. Environmentalist. Artist. Activist. The word implies that most people don’t act on their beliefs—just a small, radical subset of people.

You’ve seen plenty of political cycles. What’s your take about now?

You wonder why Trump? Everything that happens occurs because of something that happened before, but nobody wants to go back to 1973 when Jimmy Carter and his Federal Reserve head, Paul Volker, raised interest rates five points in a single day and bankrupted 22 million family farmers. There are some Trump voters for you! The Treaty of Detroit, which established that wages went up along with corporate profits. That too ended in 1973.

It was all over when Bill Clinton steered the Democratic Party away from its traditional constituency by removing Glass-Steagall to chase the same big money as the political sector. Angry voters have been sitting for years watching the same smiling men and women on the news with good hair laughing and talking. But nothing changes for the voters. They just get more angry. Unfortunately, getting angry doesn’t make you smarter. So when this orange-haired vulgarian thug stands up and sticks his finger up Washington’s ass, they say, “I don’t know, maybe he’ll do something for us.” But he’s already betraying them. Meanwhile, the Democrats are spending their time on “What kind of image can we project?” [Pounds table] It’s not about image, it’s about essence!

Nobody is addressing the core problem with our democracy, which is that we don’t live in a democracy anymore. We live in a corporatocracy. Since Citizens United and the flood of dark, invisible money that nobody knows who is giving to whom, you and I are done as citizens. We’re blaming Pinocchio for the crimes of Geppetto. Congress is Pinocchio. Geppetto is the company we buy our 500-horsepower car from or the hedge fund we give our money to.

Now you need a billion dollars to run for president. Who has a billion dollars? Even Obama, who got 40% of his budget from small donations, had to get 60% of it from Wall Street so not one person went to jail for the financial collusion scandal of 2008.

In many European countries each candidate is given the same amount of money. We watch what they do. They show up on every TV station in unstructured debates. They ask each other questions. It lasts six fucking weeks and then it’s over. In many cases corporations are prohibited from spending their treasure to influence public policy for the benefit of their stockholders.

I lived a lot in Europe, but I’m not sure we’re ready here for European-style socialism.

I’m not espousing socialism. I’m espousing an open, transparent electoral system that is paid for by the people to reinforce the fact that members of Congress work for us. And if we need to give them a raise then we should give them a raise. But they shouldn’t be able to take a fucking nickel, a free jet plane, hockey tickets, or whatever because their job is to work for us and represent us. I’m not describing their actual politics, I’m describing the way we elect politicians!

If I didn’t know better I’d say you were angry.

I am angry. I’ve struggled with anger my entire life and I’ve been watching myself in meditation for 44 years, so I’m aware when it comes up. I don’t pretend it’s not there but I don’t glom onto it. If you do something that gets me angry, I’m angry. But the next second it’s over. That’s just human.

Are you happy?

I’m very happy. My next breath fills me with joy. I’ve removed most of the stressors of my life and realize I’m walking around in this wonderful starlight and everything I see is a bloody miracle. There is no way to explain why the fundamental roiling, invisible energy of the universe produced a goldfinch, or you, or those flowers, or a shooting star. All you can do is experience the miracle of it.

Do you have any advice to readers, many of whom have a spiritual focus but find themselves struggling as spirits in the material world?

Because science has created an idea of objective facts, there’s a tendency to treat ourselves objectively as facts, but it’s a real fallacy. Nobody else on earth is having your experience of being alive. Anything you’re taking deadly seriously as important, like “I gotta have it, I gotta own it, I gotta get it,” is empty and ungraspable. It’ll never satisfy your thirst. So to the degree that you can understand and let go (or at least soften) those attachments and desires, you win freedom. The most effective tool that’s ever been devised for becoming intimate with yourself and your internal life is meditation.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.