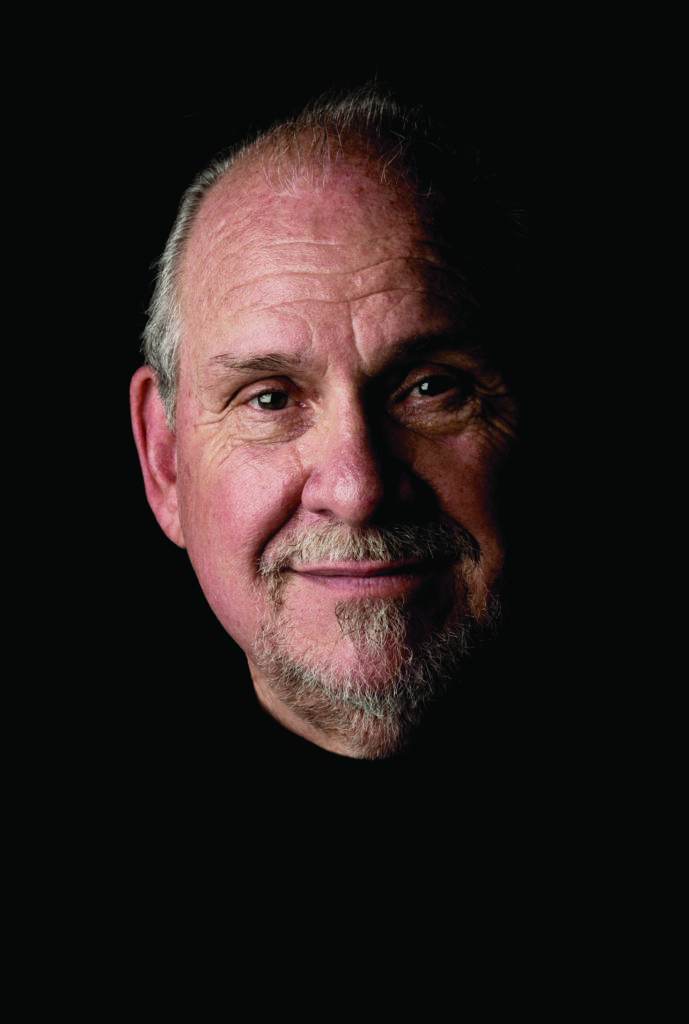

The Spiritual Odyssey of Do-Good Hippie Doctor Larry Brilliant

Larry Brilliant was born in 1944 in Detroit—where he met and eventually married his high school sweetheart, Girija. The grandson of an immigrant Jewish bricklayer, he was the first in his family to go to college. He studied science and medicine on a scholarship after his father testified against the Mafia and suffered a retaliatory hit that sent the family reeling into poverty. In the course of his first San Francisco visit during the psychedelic Summer of Love he forged his identity as a do-good hippie who enjoyed countless “on the bus” excursions such as being cast as the doctor on the Medicine Ball Caravan, a sequel to the Woodstock movie.

A chance encounter with Be Here Now author Ram Dass in New Delhi in 1971 steered the couple toward meeting their lifelong guru, Neem Karoli Baba (also known as Maharaji), who mysteriously and accurately predicted Larry’s becoming a World Health Organization doctor who would participate in the eradication of smallpox, a painful disease estimated to have killed hundreds of millions, if not billions.

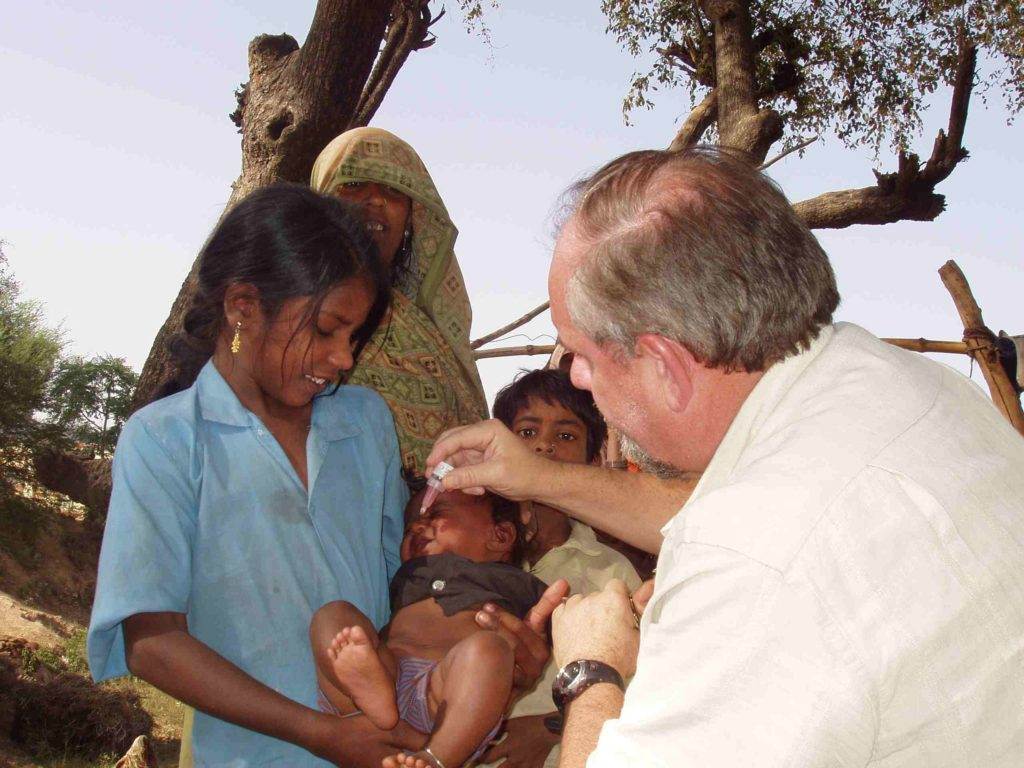

As an experienced epidemiologist drawn to Karma Yoga (the path of selfless service) as inspired by Maharaji, in 1978 he co-founded the Seva Foundation, a non-profit that has thus far restored vision to more than 5 million underserved blind people in more than 20 countries.

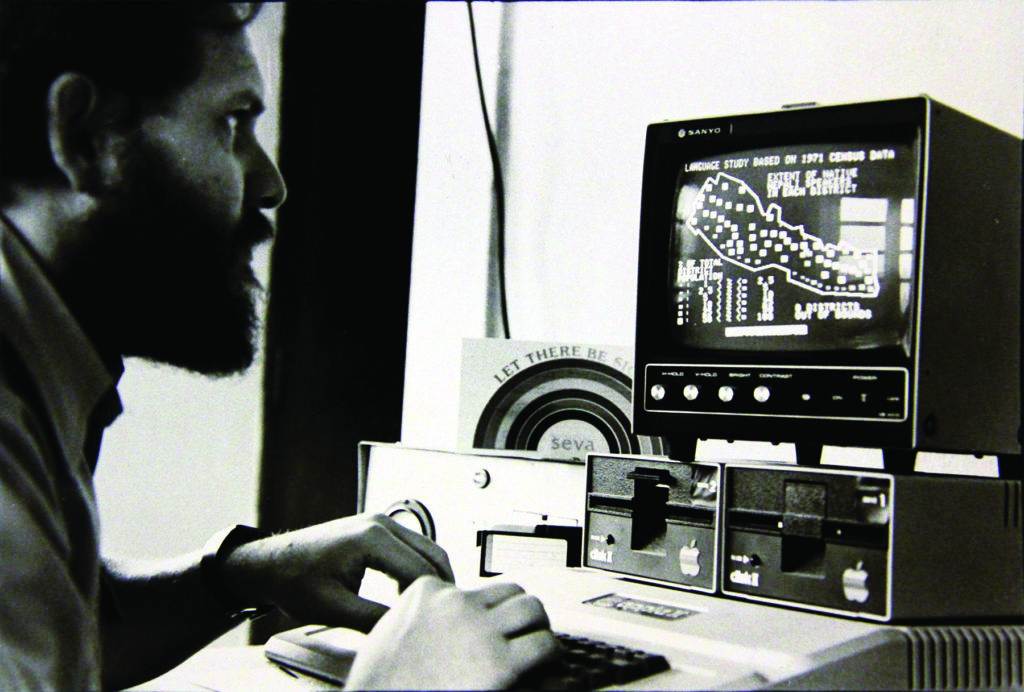

As a technologist whose early friendships with Steve Jobs and Stewart Brand led to co-founding the Well, a prototypic online community, he later became the inaugural executive director of Google.org, and the board director of the Skoll Foundation and Salesforce.org.

Defying the notion that “hippie relationships don’t last,” he has been with Girija for more than 50 years, through life’s ups and downs including the loss of their then 26-year-old son Jon to cancer in 2010.

One of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People and winner of the TED Prize, Larry humorously shares his adventures as a madcap spiritual seeker in his aptly titled autobiography, Sometimes Brilliant. We caught up with Larry in Marin County, where he lives.

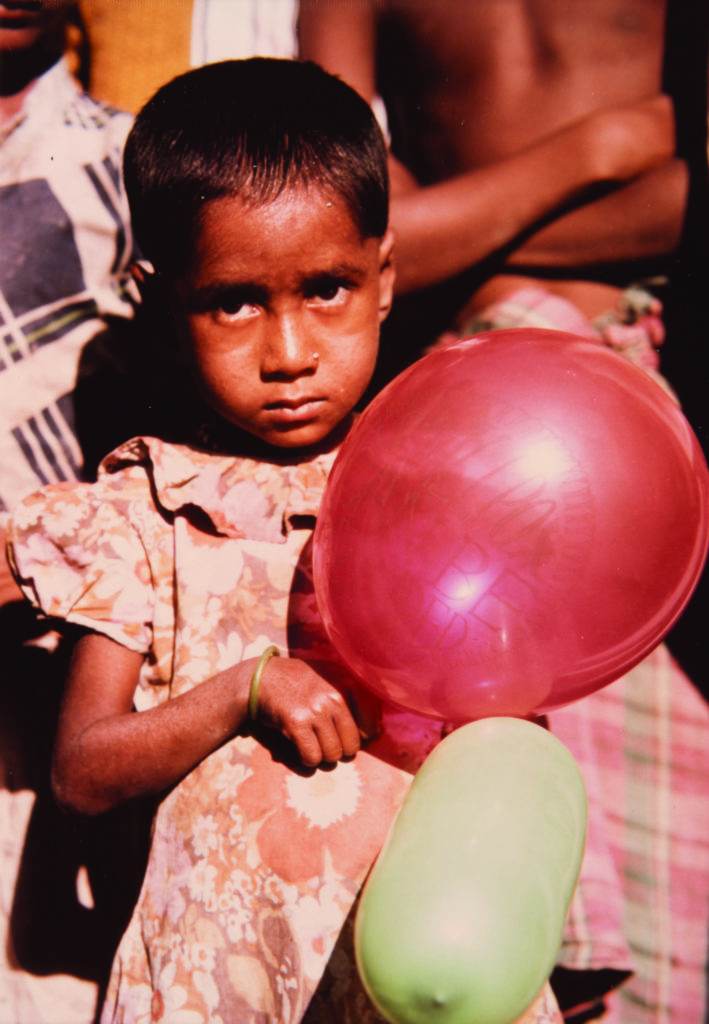

Common Ground: You helped witness and certify the eradication of killer smallpox. Would you tell the story of Rahima Banu?

Larry Brilliant: Rahima Banu was a girl on Bhola Island in Bangladesh. She contracted smallpox in 1975 and unlike many she survived. Five years later, on Christmas Day 1980, when Rahima coughed and her scabs fell off, a disease with a long unbroken chain of transmission—going back to the pharaohs—was finally eradicated. Good on us as humans! Because it took more than a village. It took hundreds and thousands from all religions and countries, Muslims, Jews, Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Shinto, Jain, and tribalists—that’s what it took to get to that place. I was but one of the epidemiologists for the World Health Organization to stand witness and certify that last case. It was an honor.

Most people have no idea about smallpox. Can you describe it?

Some people think what Job endured in the Old Testament was smallpox. Others think it was one of the ten plagues of Exodus. Imagine having one of the most painful furuncles or boils but on every single inch of your skin and inside your mouth and your nose, inside of your trachea, your respiratory system, inside of your penis, your vagina, anus—the most painful disease you could imagine. It killed hundreds of millions, maybe billions. In the 20th century alone smallpox killed between 300 and 500 million.

Your guru, Neem Karoli Baba, foresaw your role in the eradication of smallpox. Can you tell the story?

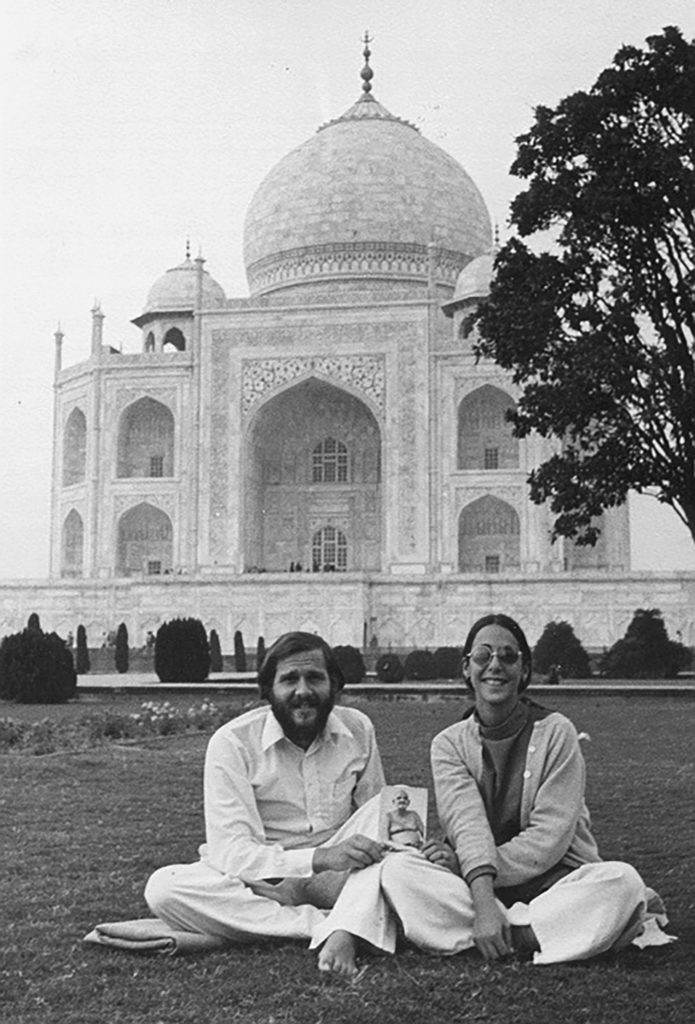

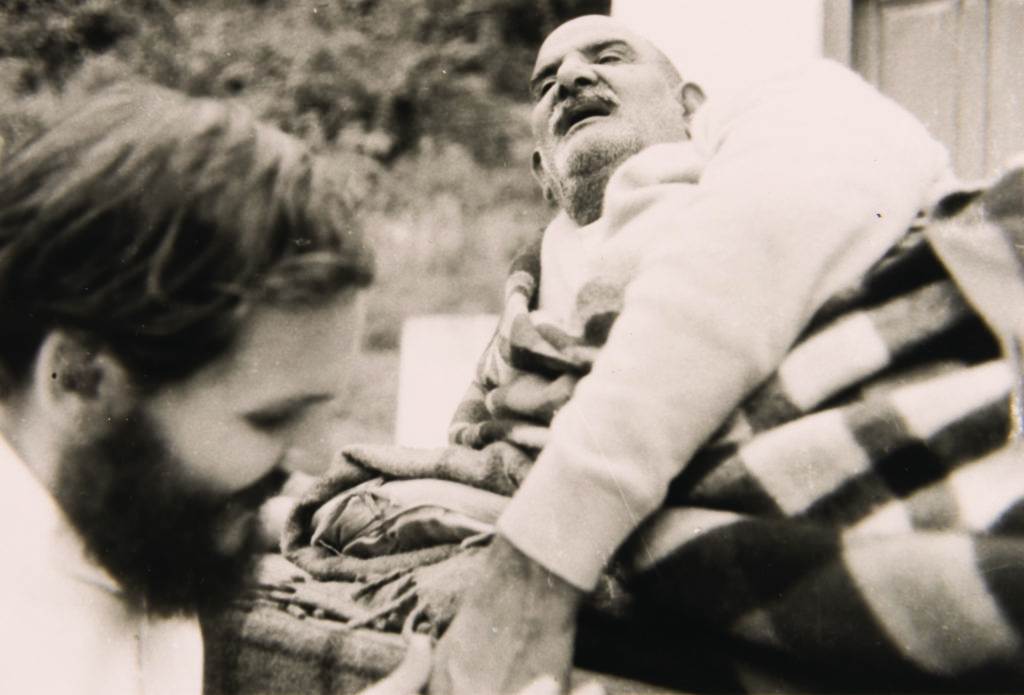

Neem Karoli Baba, who was known as Maharaji, was Ram Dass’s guru. My wife Girija and I first went to India in 1971 and bumped into Ram Dass in New Delhi at the American Express office. He happened to be picking up the first copies of Be Here Now. We didn’t really know him yet, but he recommended we visit his guru’s ashram, which we did. Maharaji was famous for always saying sub-ek, All-One. He taught that all religions, all people, everything are one. We studied a wide variety of texts from many religions and gradually became lifelong students. Maharaji nicknamed me “Dr. America.”

One day, after we had been living in his ashram for six months, out of the blue Maharaji says to me, “Dr. America! How much money do you have?” Girija and I sat there a little flummoxed. I answered, “I’ve got 500 dollars.” He said “No, no, I don’t mean here. How much do you have back in America?” I responded that I had about 500 dollars in America. He started laughing and said, “Five hundred dollars here, 500 dollars there, 500 dollars here, 500 dollars there. You are no doctor.” Now this got to me because that is exactly what my own mother had said to me: “You only have 500 dollars? You’re not making any money? You can’t be a real doctor. Why did I send you to medical school?”

Then Maharaji laughed and laughed and giggled and did this thing where his eyes kind of moved up in his head pretending to be the swami, repeating, “Five hundred dollars here, 500 dollars there. You are no doctor.” Then he got absorbed repeating, “You are no doctor, you are no doctor.” I was lost in the meaning, thinking like my mother—that I had to be a materialistic success to prove I was a physician. Then he looked at me shaking his finger as he started shifting from saying “You are no doctor” to “U-N-O doctor, U-N-O doctor.” Let me explain that while in America we say UN to mean United Nations, in India and much of the world UNO means United Nations Organization, which is what it is technically called. Then he started giggling and laughing and clapping and took my arm and pretended to jab a vaccination, saying, “Dr. America is going to be United Nations Organization doctor. You’re going to go to villages and give vaccinations against smallpox. They are going to eradicate smallpox. This is God’s gift to humanity. This one kind of suffering is going to be lifted off the backs of humanity. This is God’s gift because of the hard work of dedicated health workers.” Well, needless to say I didn’t understand. I was in a state.

His prediction was correct but not immediate, right? It took a long time.

Right, because I was just, like, “What do you mean?” He said, “Go, go to the job at the UN at WHO” [World Health Organization]. The Indian devotee who translated was emphatic: “He wants you to go to New Delhi now.” Girija and I looked at each other, not understanding, but he kept saying, “Go, go, get a taxi, go, take a bus, go, go.” So we did. We took a seventeen-hour overnight bus to New Delhi. It was daytime when we arrived and we were looking disheveled when we found the WHO office. The receptionist, Mrs. Edna Boyer, who was Anglo-Indian, greeted us. “Hello, how can I help you?” I responded, “I’m here to work for the smallpox program.” She said, “Well, we don’t really have a smallpox program. We have one person here who’s sort of looking after that.” But it was obvious when she saw me that I was not fit for working in the smallpox program or any UN program and they escorted us out.

We returned to the ashram, another seventeen-hour bus ride back, whereupon Maharaji asked, “Did you get your job?” I said, “No, no, there’s no job.” I couldn’t even get the words out of my mouth before he said, “Go back. Go now!” We thought, “Okay, we’ll stay a week this time,” but nothing materialized. Over the next two months I made over a dozen trips to Delhi and no job for me. Gradually I began to realize that wearing a white ashram gown with a beard down to my chest and hair down to my back was not the best interview suit. So I gradually trimmed my beard and traded my ashram clothes for a suit and tie. Then, through a whole set of what seemed like magical circumstances I was offered a secretarial job. Although I had graduated from medical school and finished my internship I had no training in epidemiology, no training in public health, no training in how the UN worked, and I was twenty years younger than most WHO doctors. And I was the only one ever to be hired directly in India. The only thing I had of value was that I could type and spoke both English and Hindi. They had to create a job low enough for me. I was hired as the puppy, the mascot on the team. But over time I worked my way into the field.

And the rest is history, as they say.

[laughs] That is how it started.

When you first met Maharaji, weren’t you skeptical that it was a bogus cult?

Having been brought up in a monotheistic world, the polytheistic world of bowing down to stone idols and touching the guru’s feet and the kind of worship and obeisance that’s paid is very difficult for a Westerner. I didn’t feel right about that, yet everybody else there seemed to feel perfectly fine about it. I felt like I just didn’t belong. Then a bunch of stuff happened like the story I just told, where Maharaji clearly saw into the future. Girija was the reason I stuck it out, and I learned that if you were around long enough you would see this happen time after time. That made me realize that if this was a cult I was very lucky to be there.

How was religion important growing up in Detroit?

Sadly religion only gave me something to rebel against. In Judaism you’re bar mitzvah’d at 13 and confirmed at around 16. In confirmation class the rabbi gave us a writing assignment asking students to pick between God and science. I wrote, “I pick both” [pause]. Because I couldn’t imagine a world not being more in awe of God—as a scientist [pause]. The other part of my answer was I couldn’t imagine loving God and not appreciating science as one of the methods God used to create the world.

And those were wrong answers?

He didn’t like those at all. He called me in front of the class to defend them, which I did. Then he asked that I recant. I said, “No, this is what I feel.” He said, “Well, if you feel that way you can’t be confirmed,” and kicked me out of class.

Years later I was invited to be the keynote at the American Conference of Rabbis—a huge thing at the Fairmont Hotel with more rabbis than you can imagine. I began my keynote by saying, “I’m really surprised you invited me here. I was kicked out of my confirmation class.” And they all started laughing. I interrupted my own talk and turned to my host asking, “Why are hey laughing?” He got up and said, “Because you’re the third speaker in a row who got kicked out of their confirmation class. This seems to be the career path” [laughs]. So that’s the part that religion played for me, though I love Jewish culture and the concept of tikkun olam.

Let me read you a poem from the Talmud: “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now. Love mercy now. Walk humbly now. You are not obligated to complete the work but neither are you free to abandon it.” That is my kind of Judaism.

Can you talk about your father and the example he provided? I know he stood up to the mob in Detroit.

It’s timely now to talk about immigration. Immigrants come here and take the toughest jobs and live hardscrabble in tough areas. My grandfather came here and was a bricklayer in Detroit. My father never graduated from high school, was a welterweight boxer, and earned a living running numbers on the streets. He gravitated toward the fringes but was the most gentle, kind, loving, reliable person you could ever meet. Eventually he owned a business, Brilliant Music Company, running coin-operated vending machines, nickelodeons, jukeboxes. This was an all-cash business in bars that interested the serious Mafia, which pressured him to take over his business. But he said no. The mob even murdered one of my dad’s employees, in the office.

One day, Bobby Kennedy, who was a senator at the time, came to our house. He was running the McClellan Committee, investigating organized crime. I wasn’t home but according to my brother and my mother he asked my dad if he would come to Washington and testify against the Mafia. My dad said, “Look, what they’re doing is the wrong thing, and how could I say no to a Kennedy?” Then my dad said to the family, “This may be difficult for us as a family but it’s the right thing to do.”

He went to Washington and testified. I saw him on television and on the front page of the Detroit News. But when he came back, just as he expected, the Mafia firebombed his company. They actually ran a truck into the front glass and left a fire explosive device behind. Fearing for my brother and me my dad had us evacuated on a plane to hide with my grandparents in Cleveland. Through it all my dad was impeccable. He was kind and gentle and thoughtful and thorough, but he did carry a gun. If a gun at home is supposed to make you feel comfortable, this gun made me feel exactly the opposite.

I am sorry. Didn’t your father and grandfather die within a week of each other? How did that affect you and your poor mother?

My dad died of cancer, and five days later when we were sitting shiva [the Jewish period of mourning], my grandfather died—all the men in my mother’s world. For me and my brother it was devastating but for her—I don’t think she ever recovered. And we didn’t have any money. My dad didn’t leave any insurance. I was lucky to get a scholarship to go to Michigan or I would not have been able to go. I started working, also doing vending machines because I had watched my dad do them. I had my own vending machine route. I sold papers, I sold sparklers. I didn’t know what an entrepreneur was but I became one.

When did you first come to San Francisco?

Before finishing medical school I came to San Francisco in the middle of the Summer of Love for a summer job as a civil rights specialist, working for the federal government trying to make sure that hospitals did not discriminate against African Americans. And like every young person who came from the Midwest, I had no protection against the seductive power of the ’60s. I willingly succumbed, but it was very light experience with psychedelics.

It is said of the ’60s, “You were either on the bus or off the bus,” and you were clearly on. How did you get on the bus?

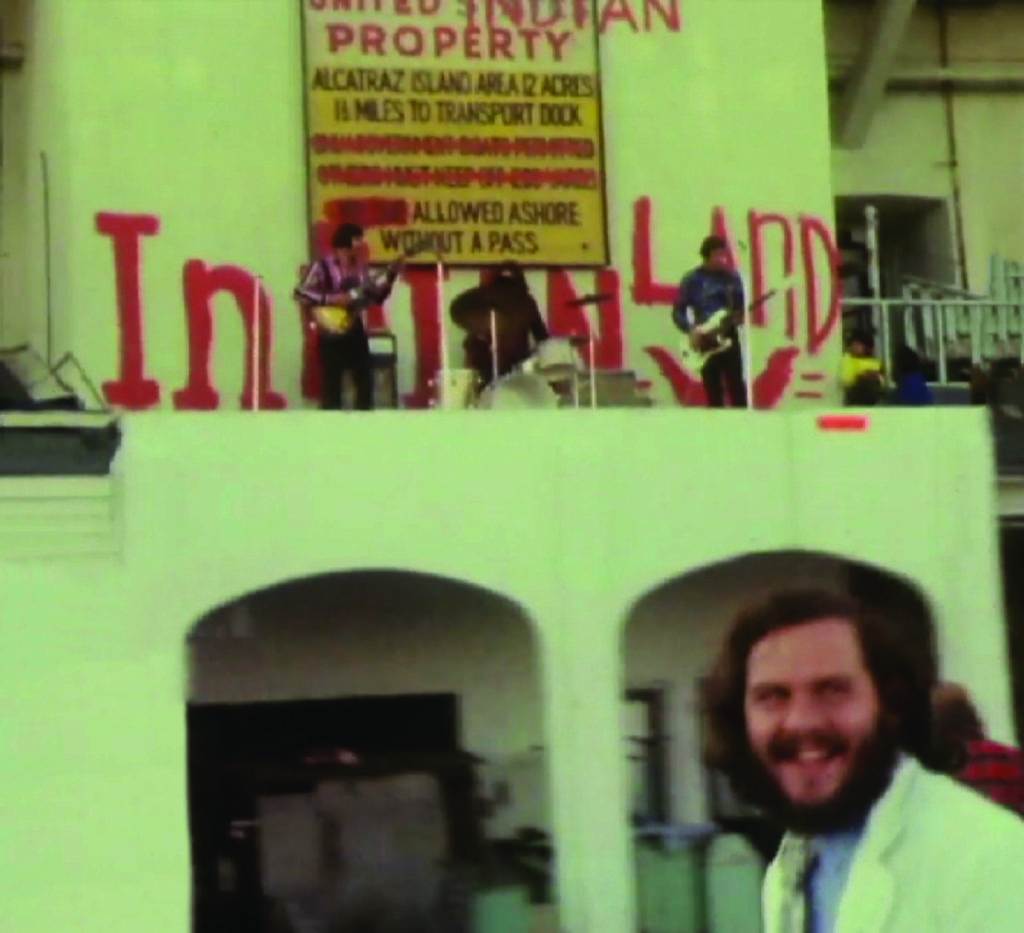

After finishing medical school in Michigan I came to Presbyterian Hospital in San Francisco to complete my internship. This is a crazy story but at one point I found myself helping amid an encampment of Native Americans who had occupied Alcatraz in protest at the time. I even delivered a baby on Alcatraz. Then at the same time there was another incident where a young Indian brave cut his arm open with a big knife [to commit suicide] in protest. I was there sewing him up, trying to keep him alive, but he kept removing the stitches. He was bleeding everywhere. Eventually a Coast Guard cutter brought us both from Alcatraz to the San Francisco docks to get him to SF General. I was covered with his blood. When we arrived at the docks there were lots of newspaper reporters and TV cameras who had come to report the story. They all asked me about my experience with the Indians on Alcatraz and this was televised quite a bit. Apparently somebody from Warner Brothers saw me on television and I was offered a job to be a young doctor in a movie called The Medicine Ball Caravan.

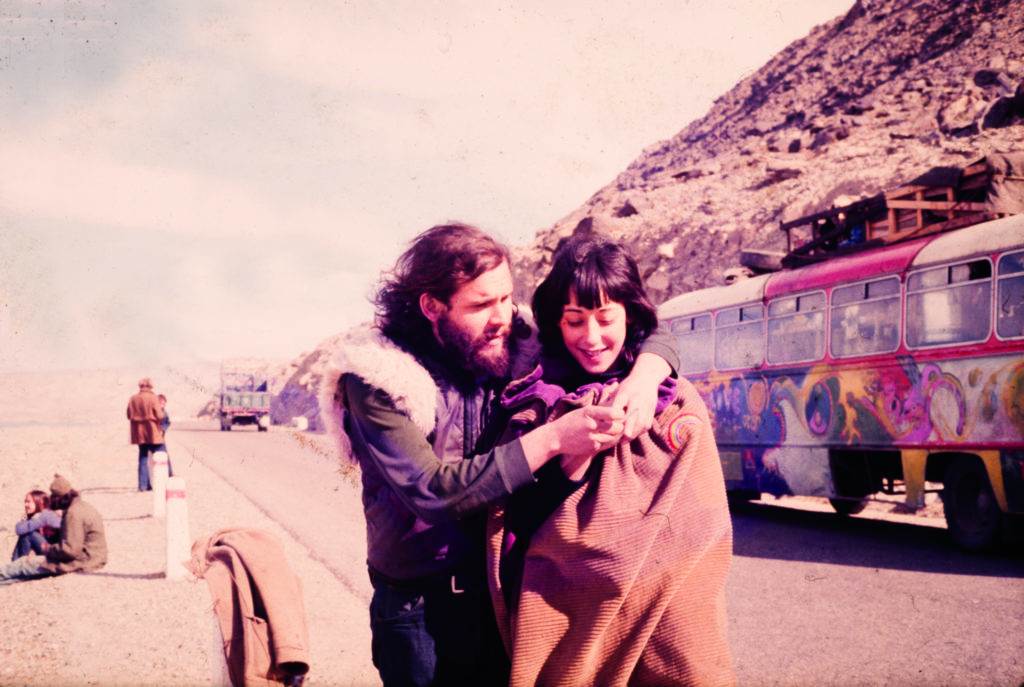

This was originally going to be about the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane and traveling with psychedelic bands—the idea being that hippies looked a lot like Indians and we were going to put up teepees and live like Indians for six weeks following these rock ‘n roll concerts. The concept was unclear but it seemed like fun, so my wife Girija and I agreed to go.

And that’s when I met Wavy Gravy, who was just so different from anybody I’d ever met—so kind, and passionate, thoughtful, truthful, funny, with rainbow-colored false teeth and a duck bill hat with a real duck’s bill! He had read everything and studied all the religions. And of course he had famously been the MC at Woodstock and had been on the Merry Prankster bus. The film had a dozen big Greyhound buses filled with actors and actresses and one was the Hog Farm bus, which was basically a spinoff of the Prankster bus. We rode with them and I found myself getting closer and closer to Wavy and happier every time.

The bus tour ended in Washington D.C. and then we were flown to London for the finale, which was a Pink Floyd concert. After The Medicine Ball Caravan journey was finished in London, Wavy suggested we keep the party going by getting our own buses to go through Europe, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and India to get to East Pakistan, which is now called Bangladesh. There had been a huge cyclone there and the idea was to do good by bringing medical supplies and food and having fun. Helping and having fun—that’s what we wanted, so Girija and I again joined.

There was civil war between East and West Pakistan so we never made it all the way to East Pakistan, but instead took a left turn into Nepal where we had all sorts of hippie adventures. Wavy has been my best friend for more than 45 years. That’s a long way of saying I’ve always been on the bus and we’re still part of the Hog Farm.

For someone who came of age in the era of hippie free love, you’re something of a conservative, having been married for more than 50 years. What’s the secret sauce?

[laughs] They said “Hippie relationships will never last” but Wavy and his wife Jahanara have been married for 52 years. Every relationship has its own secret sauce. Girija, who was Elaine before changing her name in India, was fifteen when we dated in high school. I was sixteen. During college we were apart and I missed her and called her once a year to say “How you doing?” She thought it was weird.

In my last year of medical school I happened to go on a date to a play at The Living Theater, and sitting right in front of me was Elaine. I just couldn’t believe it. I was so happy to see her. I kept talking to her. Her date wasn’t happy that she was talking to me and my date wasn’t happy I was talking to her. That night I just happened to have a pomegranate with me. It’s not like I carried a pomegranate wherever I went but I must’ve been shopping and bought one. I just reached over and handed it to her. The pomegranate symbolized something for us, maybe craziness. The next day we started dating again and never stopped.

You had three children together and shared the same guru. I know that in 2010 your then 26-year-old son Jon died of cancer, which led you both to lose faith, at least provisionally. Can you tell that story?

Jon was our middle child and the life of our family. When he died we were very broken, as if none of our spiritual training nor seeing all those dying children in India had prepared us for this, and we were mad at God. We were mad at Maharaji.

A guru is a lot of things. Guru means “dispeller of darkness.” It means “teacher,” like a rabbi or priest, but in Hinduism there’s this idea that your guru is someone who knows you throughout many incarnations and is like your soul doctor. In that sense some people think your guru is kind of an insurance policy. Certainly many people around him would think of Maharaji that way. Like if your car broke down Maharaji will find the tow truck to come. And if your child was sick you would call Maharaji and in some way hope that the child would become better. When my child became sick he didn’t become better, he died. And it seemed so unfair.

Perhaps it’s a silly superficial way to think about your teacher but we sort of thought he was covered by the United Insurance of Maharaji policy. And of course he wasn’t. And despite all the wonderful things that had happened to me, all the wonderful blessings and people I had met and the work at WHO, he died. And because my training program included seeing thousands of little babies die, so many in my arms from smallpox, I thought I was prepared for anything. Of course I wasn’t.

We know of a couple of other families, who when somebody died they took the guru’s picture off the wall. I think the closest we came was we took his picture and turned it with his face to the wall for a few months as we were unable to talk about it or to seek solace or consolation in any of the great teachings or prayer. Then as the acute pain began to diminish we realized that there had been so many joyful days. We did not want to lose the wonderful things about how bright and lively and smart and funny and full of love Jon was—to not let him die twice. That helped us. We started thinking our spiritual job was to make the days of joy of his memory exceed those of pain. Sometimes that works, other times it doesn’t.

How do you think about Maharaji now, who left his body more than 45 years ago?

It’s extremely inconvenient. I’d love to talk to him right now. But I do in a way. There’s a conversation always going on in the background.

Going back to the hippie days, how did psychedelics play a role in opening you up to Eastern spirituality or Maharaji?

I’m a scientist trained in medicine and before that I trained in nuclear physics. I don’t think that I would have been able to see Maharaji (in the sense that Castaneda uses the word see) if I had not taken psychedelics. My mind would not have permitted the kind of logical conundrum of someone like Maharaji who clearly lived in a different dimension.

As a hippie doctor with the advantage of retrospect, how can you advise young people who may be tempted by the lure of psychedelics?

I’m really torn by that question because it’s a fraught subject. It’s an individual thing and not generalizable. If it were my kids it’s not going to be a one-word answer but a looong conversation. I am grateful for psychedelics but we also didn’t have the widespread yoga, meditation, and all the other alternative ways of getting to the same answers. Those safer alternatives are more accessible now. I’ve seen people who turned out wonderfully and I’ve seen people dead in elevator shafts with needles in their arms. I saw a kid at a Rainbow Gathering filled with LSD thinking he was God and could fly. He leaped off a cliff and died. I pronounced him dead. Widespread irresponsible use of psychedelics as a party drug is so dangerous and sacrilegious and de-values the magic. Gnōthi seauton—that is the Greek inscription written above the famous Oracle of Delphi. It means “Know thyself.” That is always going to be the real answer.

Guru devotion is so misunderstood, particularly in the West. Were you ever cagey about showing your devotion, especially within scientific circles?

No. I learned from Ram Dass early on that if you have a secret then go public with it. For a long time he felt it diminished him that he would talk about everything in public but not that he was gay. He tells the story about how he and his boyfriend were standing in line to see a pornographic movie when this elderly woman says, “Ram Dass, oh my God. My life is complete. I’ve been reading Be Here Now and [pause] what are you standing in this line for?” And Ram Dass said of all the conversations he’s had that’s the one he thinks about so often because he was leading a double life. The next day in a speech he said, “I am a gay man.” And it was so liberating. First he realized that nobody cared at the level they did in the ‘50s and everybody was thrilled that he was that open with them. So I learned to do the same thing about your love for your guru. Hey, I’m an old antiwar hippie spiritual guy who lived in a monastery—who likes to play golf. That’s my dirty little secret. [laughs]

You co-founded Seva Foundation. Can you explain the background and ideology of Seva?

This is the path of Karma Yoga. There are many yogic paths but the idea that Maharaji taught me most is Karma Yoga—of merging with God through acts in the world. The key is to have no attachment to those acts, no holding on, no taking credit. Seva Foundation started 40 years ago because I felt like I got too much credit for the smallpox eradication. I felt like an imposter since I was the mascot. Later I became a professor of epidemiology and learned so much more that I felt like I wanted to do it again. And so did the other people who had been in the smallpox program.

Girija and I wrote an article called “Death of a Killer Disease” that was published in Quest, which is a Christian magazine that was widely read. For some reason a lot of people started sending notes in the mail that basically said, “Keep doing what you’re doing.” And money. We got envelopes filled with checks and cash—more than $20,000 worth. So we had to figure out what to do with it. Girija said, “Let’s call together a meeting with all the people we wrote about in the article and ask them what to do with the money.” So that led to a meeting of the most improbable people you could imagine. Lots of United Nations diplomats, lots of CDC epidemiologists, Dr. Nicole Grasset, Michigan professors, Ram Dass, Wavy Gravy with his propeller beanie. There was a Catholic nun, Lama Surya Das, Hog Farm friends, Neem Karoli Baba devotees—we were a funny-looking group.

At the meeting we asked, “What should we do with the $20,000?” We thought we would use the money to pay the expenses for everybody’s coming to the meeting but Nicole Grasset was most adamant that we should work on eradicating needless blindness. And instead of spending $20,000 for the meeting the attendees kicked in another $20,000 and that’s how Seva started—to help provide critical eye care to underserved communities. Steve Jobs kicked in another $5,000 and joined the board and became one of our secret Santas. Seva has helped 5 million blind people regain their sight in more than 20 countries.

And you throw great parties! Can you talk about your friendship with Steve Jobs and how he was spiritually motivated?

In some ways Steve was one of the most profound spiritual seekers I’ve met because he was so intense and determined to find the answers to questions that everybody looks for. He read about Neem Karoli Baba and after dropping out of Reed College flew to India to meet Maharaji, but by the time he got there our guru had died and been cremated. Steve felt like all of us, lost. We’d all felt we lost a parent. Steve stayed in the ashram for six months, shaved his head, became vegetarian, walked barefoot, and ate only living foods, which is difficult to do in India. He hadn’t started Apple yet. He was one of the young hippies just like I was one of the young hippies.

Back in America he wrote me about how impressed he was with the idea that you could have a global impact eradicating a disease. He visited me a couple times in Ann Arbor while we were thinking about starting Seva. We’d go for walks talking about the meaning of life. He was always on fire when he talked about that. He was a wonderful man. I’ve heard these stories about what a mercurial manager he was but when he was running Apple when it had 17,000 employees there were 17,000 people who would laid down in front of a train for him. That’s who he was. He was that kind of a leader.

You were a co-founder of the Well and the first executive director of Google’s foundation as well as a director of the Skoll Foundation and Salesforce.org and have lots of experience with the tech elite. There is an unprecedented wave of mindfulness infiltrating Silicon Valley and I wonder how you gauge the spiritual consciousness of that trend?

Meng Tan, who was one Google’s first employees, and Mirabai Bush created a program called “Silly” for Search Inside Yourself. They began teaching meditation at Google. The techies loved it. And it went to so many other places. Salesforce founder Marc Benioff is a meditator and the company has meditation rooms on all the floors. We had an event at Salesforce called Dreamforce, where I was one of the speakers talking about mindfulness, reminding that one should never talk about mindfulness without also talking about compassion. Because mindfulness alone—if it is to give you a tactic to be better at your work, or more alert—if it isn’t for the purpose of being more compassionate, then it’s not the real mindfulness.

Comes back to that funny rift between do-ers and be-ers. Is it more important to do—or to be? Do? Be? Doobie do be doo. [laughs]

That schism became our inner joke at Seva. Ram Dass represented the be-ers and always wanted Seva to slow down and smell the flowers, work on ourselves and interpersonal relationships. Meanwhile Dr. Nicole Grasset and Dr. V (Govindappa Venkataswamy) wanted us to do more and more eye surgeries.

Once there was a huge fight between Ram Dass and Nicole in our garage in Chelsea, Michigan, at the second or third Seva meeting. Ram Dass was essentially saying, “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?” Or what do you gain if you give sight back to 100,000 blind people but lose your way? And Nicole said, “Who gives a damn about my soul? I don’t matter! I could roast in hell as long as I know that there’s no more suffering in the world! I will be content.” It was like watching Mother Theresa argue with the Dalai Lama—a wonderful moment. They’re obviously both right. Do-be-do-be-do! [laughs]

Pranksters like Ken Kesey and Wavy Gravy clearly had their own brand of altruism, though not necessarily with the spiritual overlay.

Kesey was an incredibly spiritual person, larger than life. I once heard Stewart Brand say that Kesey was one of the most Christ-like people he’d ever met. Wavy is really one of the deepest and most profound mystics but that’s a part people don’t know unless they watch his movie Saint Misbehavin’.

What are your concerns for future generations and the planet?

I wonder what Mother Earth thinks about us calling this the Anthropocene era! [laughs]

I’m conscious that after World War II we watched the gut-wrenching horror show of skeletons emerging from the concentration camps and the mushroom clouds, the tens of millions of dead soldiers. We saw what human beings could do to each other. We peered over the abyss and looked into hell and collectively said, “Never again.”

Every country agreed, without even talking about it, to give up a little bit of its sovereignty believing we were all in it together. A torrent of new organizations was created such as the UN and WHO, the Security Council, and so many more. We witnessed a rush of centripetal forces bringing us to the notion of one global village. Today it’s the opposite. We have centrifugal forces fleeing the center, splintering us apart, trying to divide us by religion, by gender, by race, by geography. Nationalism. Provincialism. Dutarte. Ertegun. Putin. Brexit. Trump. Xi. Just keep naming ’em.

I think it’s logical that we should be concerned about global threats such as pandemics because who’s going to stop it? Who will respond if everybody goes back to their nation state trying to stop the virus at the border without caring about any other place? What about climate change? It is not something that can be fixed by nationalism. What about water? The melting of the Himalayas? Nuclear weapons? Cyber weapons? If nationalists abrogate all of our treaties the world becomes much more dangerous. Global issues are solved at a global level and provincialism is the opposite.

How would you grade your generation’s report card?

We would get an Incomplete [laughs]. The story is not in yet. It was quite an eye-opener when I listened to Newt Gingrich as he created his Contract for America that led to the Republican takeover of Congress. When asked what was his motivation he said he was so offended by the counterculture that he wanted to do the exact opposite of everything we did in the ’60s. At that moment I realized the great law of physics, that for every action there is an equal but opposite reaction. It is also true for social movements.

In that light I look at the rise of the Tea Party and right-wing evangelical Christian communities and I think of the kind of freedom, experimentation, alternative living arrangements, alternative sexual and marriage arrangements, communal living, disdain for materialism, and kind of nascent hedonism that fueled the hippie movement. And while I loved it and still think it was one of the greatest moments in American or world consciousness, I would be disingenuous not to not remind myself of the kids who died in elevator shafts with needles in their arms or the one on LSD who leaped off a cliff. So you can’t look at the hippie movement, the drugs, without recognizing that there were externalities—both great ones and sad ones. It was great for some. It wasn’t good for everybody.

How might you compare the enthusiasm and zeitgeist of the ’60s to today?

Millennials are much like we were in the ’60s. Yes, there are jokes about Millennials being unable to get anything done because of their endless narcissism but that’s not my experience. I see a generation much like ours, pushing the boundaries of inquiry, trying to break down barriers. Look at the rapidity with which gay marriage is accepted within the Evangelical youth community! In Silicon Valley, Millennials won’t work for a company that violates their values. They vote with their feet and walk out. I see a generation inheriting the best of all that history has provided including the kinds of mindfulness practices we talked about earlier.

You’ve been at this a long time. Do you ever feel jaded?

I’m not jaded at all. I still believe in God and Maharaji and as bad as it is—we’ll get through this. It’s been much worse. We forget that they called them World Wars because they were world wars! Far fewer people are dying in uniform. In the last 50 years the life expectancy has increased by more than 25 years. The percentage of people living below poverty has dropped by 50 percent. When I was working in India and Bangladesh 50 percent of children died before the age of five. Yes, the world could drift toward fascism. We’re certainly flirting with it in many countries but I see so many good things.

A final message to Common Ground readers?

Stick with it. Don’t give up. The journey of self-discovery, the journey to creating a fairer and more equitable world, of combating racism and sexism and all the isms—hatred—these are lifelong battles. Nobody said it was going to be easy. Martin Luther King quoted a Unitarian minister who said, “The moral arc of the universe bends toward justice.” But he did not say that gravity alone made it bend. He said, “If you want that arc to bend toward justice it needs your help.” You’ve got to jump up and grab that arc and bend it down. It doesn’t bend toward justice on its own.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.