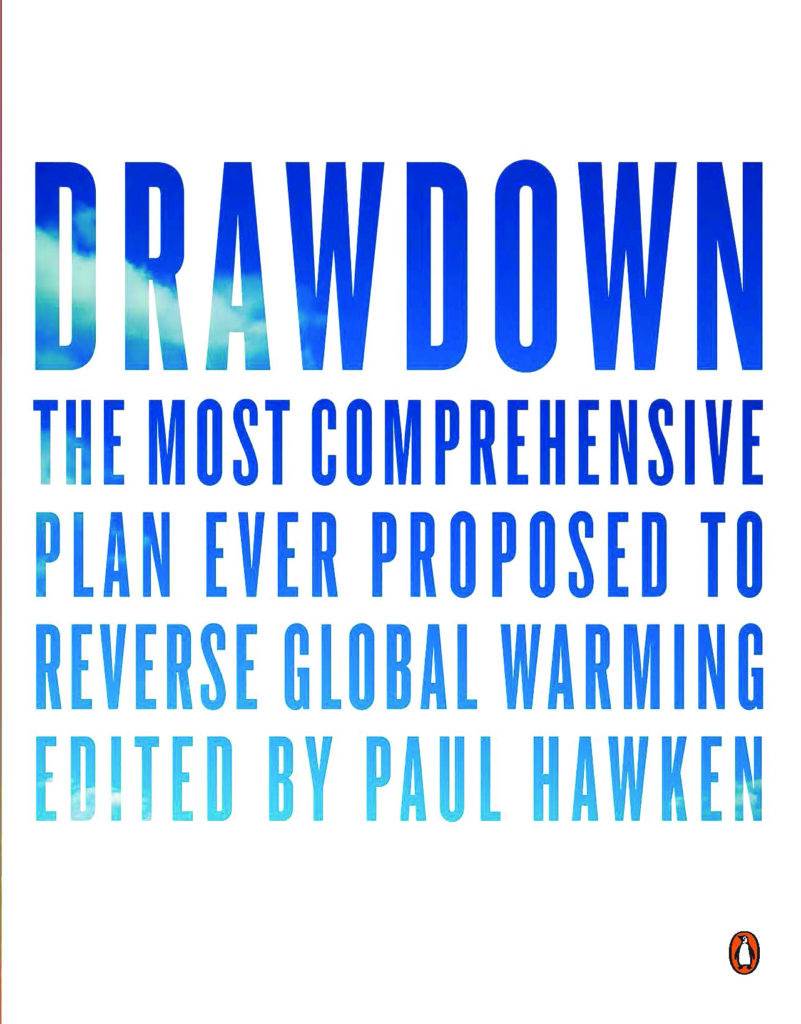

THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE PLAN TO REVERSE GLOBAL WARMING

Paul Hawken is a longstanding environmentalist, entrepreneur, and activist whose nonprofit Project Drawdown is dedicated to reversing global warming within the next 30 years. Born in 1946 in San Mateo to what he says were “pretty bad” parents, he found solace in the complex mysteries of the outdoors. His father worked at the University of California (Berkeley), where Paul enrolled for a short period before realizing he needed to leave to pursue his lifelong purpose—learning. He never resumed his formal education but went to Alabama to volunteer in the press corps with Martin Luther King, Jr. at the beginning of the historic march from Selma to Montgomery. As a photo journalist he narrowly averted being kidnapped by the same murderous Ku Klux Klansmen he was trailing in Meridian, Mississippi.

His prescience led him to form many socially responsible businesses (a concept he helped pioneer) starting in 1966 with the Erewhon Trading Company, one of the first organic food wholesalers. In 1979 he co-founded Smith & Hawken, an upscale garden supply company, and in 2009 launched One Sun, an energy company focused on ultra-low-cost solar based on green chemistry and biomimicry.

He is the author of numerous books, including four national bestsellers, The Next Economy (1983), Growing a Business (1987), The Ecology of Commerce (1993), and Blessed Unrest (2007). Drawing from the expertise of a broad coalition of researchers, scientists, graduate students, PhDs, post-docs, policy makers, business leaders, and activists, he initiated and edited Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Proposed to Reverse Global Warming, given a triumphant reception when released in April 2017. A landmark book that is solutionsbased and optimistic, it became a bestseller within a week. We caught up with Paul to learn why he believes global warming is the concern that subsumes all others—“the one true common ground we share”—a goal so essential it raises the question “Why are we here?”

Common Ground: You have an interesting background as an environmentalist and entrepreneur and spiritual seeker. How would you describe Paul Hawken to someone who’s never heard of Paul Hawken?

Paul Hawken: I wouldn’t even dare to except with one word—learner. My whole life is about learning, and the rest, whether it’s on the business side or the writing side or the activist side, or understanding my mind—these are just manifestations of learning. I was frustrated with the public school system. High school was four years of hell. My father taught at the University of California so I went there as a freshman with 500 people in the class for the prerequisites and it was just so impersonal and unsatisfying that I left and decided to spend the rest of my life learning.

Could you talk about growing up in the Bay Area with all these different perspectives? Was there a turning point when you began to heed the call about environmentalism?

Our family belonged to the Sierra Club at a time when that was more about being outdoors. And I did meet David Brower when I was 10 or 11 years old and he made a big impression on me. I remember another incident then that had a big effect on me. That would’ve been in 1959. We were going to camp at Porcupine Flat in Yosemite when we passed this RV in the middle of the woods and it was opened up like a little house with chairs and a patio veranda. I think it had a TV plugged into a generator. I was so startled and remember saying to my dad, “How can this get in here? Isn’t that against the law?” I thought of Yosemite as a place where you disappeared into nature with everything on your back, not where you stayed by the car for food, warmth, comfort. It was the invasion of technology—civilization was encroaching.

Did you have a happy childhood?

I didn’t have very good parents. I would say they were pretty bad, actually. My house—I wish I could call it a home—wasn’t safe inside. So I spent as much time as possible outside, where I did feel safe. When you’re inside there’s a light switch, there’s a wall, there’s a bathroom, there’s a refrigerator. You can master the inside of a house quickly, no matter how old you are. But outside it’s so diverse and complex. The bugs and the birds and the sounds and the trees and the leaves and the things that crawl around. There’s so much going on and you don’t have names for it. Trees don’t have switches and nature isn’t mechanical so what developed was an intense curiosity: “What’s that sound? What’s this doing? I don’t understand that. Is this edible?” Curiosity is actually the admission of not knowing—which is nice. Writing and journalism are about not knowing, then asking questions and examining. It stems from curiosity—from that comfort of not knowing.

Was there anything in your family’s religious or spiritual background that inspired curiosity?

Nothing. I was an altar boy but that had the opposite effect. The Catholic Church was about didacticism, hard and fixed beliefs, and victims—“Thou shalt, thou shalt not.” It was cut and dried and hierarchical and the opposite of Nature. Spiritual curiosity got developed by being outside in a very complex, intricate and interconnected, and mysterious environment.

Is climate change—you say global warming—the most pressing environmental concern you’ve seen in your lifetime?

Yes, because all other environmental issues are subsumed by it. And yes, I don’t call it climate change—I call it global warming. Climate change is not a problem. Climate changes every nanosecond. If it didn’t we wouldn’t have food and evolution and all the beauty and blossoms right now. Global warming—that we have to be concerned about. The hotter it gets on earth and in the atmosphere the more volatile the climate becomes in terms of its rate of change.

You’ve been working on Project Drawdown for a long time. Could you describe it?

For the last 2 million years our genus, Homo sapiens, has not lived on Earth when there’s been over 300 ppm (parts per million) of CO2 in the atmosphere. In the last 10,000 years of the Holocene Era the ppm has hovered around 220-250. In about 1939 it exceeded 300 ppm. Right now we are at 490 ppm when you take into consideration all greenhouse gases including CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, and HFCs. So we are nearing twice the levels of greenhouse gases from the time our species evolved. We haven’t seen anything like this for 20 million years and of course we didn’t see it because we weren’t here. So we are way out of bounds. Drawdown in this context means the first time when greenhouse gases peak and go down on a year-to-year basis.

Yikes!

We don’t really know where we are—this is terra nova. And there is a lag time between an increase of greenhouse gases and its impact on climate, weather, the hydrologic cycle, ocean levels, heat and drought, and turbulence in terms of extreme weather and storms. It’s not a one-to-one ratio. The earth’s atmosphere is an extremely complex and resilient system but we can mistakenly associate the buffer created by that resiliency with the idea that everything is okay. It is not okay. So the important thing about Drawdown is that we named the goal—not to mitigate climate change, but to stop and go the other way—to reverse global warming.

Different activists state different goals.

I thought we should name the goal because if we don’t name it how are we going to achieve it? And it wasn’t being said. What’s being spoken, as if the Paris Agreement were being adhered to (which it’s not, by the way), is this idea that if somehow we could achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 then somehow we get a hall pass into the 22nd century. Right now we’re heading off the cliff with greenhouse gas levels at 490 ppm in CO2 equivalents. Stabilizing emissions means we’re only slowing down the rate of warming. We’re not really changing anything; we are not reversing emissions. Essentially we just go over the cliff a little more slowly.

By 2050, which is the Paris timeframe, we’ll be somewhere around 550, not 450. It’s a mistake to assume that the Paris Agreement would lead to climatic stability. What we hear is that if we slow down, accelerate the use of renewable energy, solar and wind, and listen to Elon Musk, then everything is going to be great. That is scientifically untrue. Of course, replacing carbon-based fuels—coal, gas, and oil—with clean energy is crucial. Electric vehicles are crucial. However, there is this idea that if we get those things done in time everything is going to be okay. It’s not.

Drawdown’s model comprises 100 solutions?

Project Drawdown is a research collation that mapped, measured, and modeled the 100 most substantive solutions to reducing global warming. The solutions modeled are extant, already in place. There is abundant scientific data on their impact. There is extensive economic data on how much they cost and the net savings. The solutions we modeled are scaling right now. The question from a research point of view was, “If these solutions continue to scale at a rigorous but reasonable rate, could we achieve drawdown by 2050?” By the way, that’s not the end of global warming. After drawdown there’s a 20+ year lag at least before you start to see cooling. But you can’t see cooling until you start reversing emissions, which means returning carbon back home to Earth where it came from.

It’s a give-and-take thing, no?

There are two things you can do about the atmosphere. You can stop putting greenhouse gases up there whether CO2 or methane or nitrous oxide or refrigerants, HFCs. This is called avoided emissions. The other thing you can do, which has not really been talked about much until the last couple of years, is bring carbon back home. That’s called biosequestration. That’s done on land by photosynthesis by trees, grasses, and plants and in the ocean by kelp and algae.

I’ve been poring over the 100 solutions. They’re fascinating and unexpected. For example, the importance of educating girls, and family planning—those are super high on the list.

The number six solution is educating girls and number seven is family planning. You put the two together and you basically have the number one solution to reversing global warming. Educating girls has innumerable benefits starting with the fact that a girl who has been supported in her education becomes a woman more on her terms. Millions of girls are pulled out of school when they’re at puberty (or before) for a variety of reasons. If the family is poor it could be that the girl goes to work to put her brothers through school. Another cause is early marriage. Whether it’s cultural, traditional, religious, or pragmatic, girls who do not receive a full education have an average of 5+ children and they don’t earn as much money because of that lack of education. Her children are impoverished and they too don’t get the education they deserve. This creates a vicious cycle. A young girl that is supported to matriculate through what we would call high school makes very different choices. On average she has of 2+ instead of 5+ children.

Thus, education is a form of family planning. When you combine that with the traditional sense of family planning, which is having clinics available everywhere in the world to support women’s reproductive health and services, that will make the difference between the high and median UN population projections for 2050. That would mean 9.7 billion people instead of 10.8. The UN is clear that the difference is almost entirely due to family planning.

Another example I discovered is silvopasture, which is number 12 on the list. Can you describe that?

Silvopasture is just like it sounds, “silvo” being trees and “pasture” being grassland—it’s the interconnection or interspersing of trees and grasses, which produces a much better environment for the animals raised there. It produces more water in the soil and sequesters a lot of carbon. Silvopasture has been practiced for 2,000 or 3,000 years.

An oldie but goodie.

A lot of these solutions have been around a long time—like solar. The first solar panel went up in 1884 in New York City. The first coalfired plant went up in 1882. At the time there were dueling op-eds about which would prevail, solar or coal? I quite humorously say solar won—it just took a while!

LEDs go back to diodes in 1874 when they were invented. The fact that diodes emitted a light won a Nobel Prize in 1960. Going forward virtually every light fixture will be LED by 2030. Many of these solutions have deep roots, which is different from the idea that there’s some silver bullet somewhere that is going to solve our problem. We’re saying that we already have a vast array of effective solutions, have great mastery over them, and they’re becoming less expensive and more effective.

It’s been said that the most significant thing any one person can do to reduce global warming is transition to a plant-based diet.

The number one thing that an individual can do is reduce food waste, especially in the United States where we waste 40 to 45% of all our food—133 billion pounds a year. It’s the number three solution but the number one individual solution. And that’s not counting the methane emissions when food is landfilled. Methane is 28-36 times more powerful than CO2 for warming.

We are all a bit unconscious about wasting food. We cook too much and don’t eat it the next day. It gets put it in the refrigerator, where food goes to die. It gets scraped into the garbage disposal. We do it so unconsciously. People don’t finish their sandwich. Look at a restaurant and watch what’s being cleared from plates. Watch the busboy. Watch the table next to you. Supermarkets buy too much produce and as soon as any doesn’t look good in any way, shape, manner, or form they toss it. Food waste is extraordinary in the United States. It is dishonoring at many levels, certainly to the farmers and people who make it for us, and to the atmosphere.

How did you narrow to 100 solutions?

We had a big basket and put names in it—very low-tech. We had lots of lists of solutions in the basket, maybe 300, not sure. Then we selected them by sector and then we would do back-of-the-napkin calculations followed by more in-depth calculations—still not modeling it but more in depth. And then we whittled that down to 100. And then to 80. We include 20 more solutions we call Coming Attractions that are scientifically valid but for which there is not sufficient data as yet.

Then we spent three years modeling, not knowing what the outcome would be until about two months before the book was published. It’s fair to say we were very surprised at the numbers. So much so that in several instances we would look back at the model and say, “Are we sure? Is this true? It’s not what we expected.” I don’t think anybody in the world expected the top 10-20 solutions because we’ve been told repeatedly by Al Gore and others that it’s pretty much all about clean energy.

Those solutions are critically important but we’ve been spoonfed oversimplified versions of what it takes to address global warming. I think that’s where Drawdown has made an original and hopefully significant contribution, which is to give people a sense of possibility with all the different ways that we can reduce and reverse global warming.

A serious group effort!

Project Drawdown consists of young research scientists from 22 countries, 20+ advisors, and some 40 outside expert reviewers of the model. My original ask of my publisher was to put the 200+ people on the cover who collaborated to create Drawdown. The publisher preferred a single known name so I put “Editor” after my name. Drawdown is about working together; it is about feeding, not leading. It’s about giving, not taking. It’s about generosity. It’s about learning and not knowing. I want to emphasize that. I had a role but so did many other people. I don’t want to take away from Katharine Wilkinson, Chad Frischmann, Janet Mumford, Crystal Chissell, Eric Toensmeier, Mamta Mehra, Kevin Bayuk, Marianna Leuschel, Ryan Allard, João Pedro Gouveia—all these amazing people who worked together to create this. I don’t want this to be about Paul Hawken because that’s inaccurate and not helpful.

The book is successful.

It’s interesting because although my editor has successfully been with me for more than 25 years with four New York Times bestsellers, Penguin Random House told us in a nice respectful way that they were reluctant to publish the book. Why? It’s just a given—climate books don’t sell. But anyway they did. And it became a New York Times bestseller in the first week.

Do you attribute that to the fact that you differentiate yourself by not having all this catastrophic doom and gloom language?

I think the reason is because it doesn’t blame, shame, demonize, and threaten with doom scenarios. It’s not trying to divide the world between good and bad. It’s speaking entirely to possibilities. Most of what we hear is about the probability of what’s going to go wrong, when, how, and how much. We think climate science is some of the most kickass science ever. Drawdown is very much about honoring the science but not about the repetition of what’s going to go wrong. Ninety-seven of our 100 solutions are what we call “no-regrets solutions,” which means we would want to do them if there were not a climate scientist alive and we were clueless as to what was causing extreme weather. Why? Because they have so many benefits for women, children, the water, health, the air, jobs, prosperity, education.

Could spend a minute talking about your scientific methodology?

We started out with a handful of people but we didn’t have money, which turned out to be a blessing. So we put the word out to top-level universities around the world for Drawdown research fellows and offered to pay them $1,000 (which eventually became $2,000) to basically do a master’s thesis on a single solution. On top of that we created an advisory board that included botanists, biologists, architects, technologists, activists, writers, faith-based people, religious teachers, indigenous people to be our content advisors. It was as diverse as possible in terms of interests and range of expertise. On top of that we got outside scientific reviewers who reviewed the model itself.

Every data point, whether impact, rates, costs, savings, is conservative. We didn’t want anybody at the end of the day claiming we exaggerated, or as they say in England, that we “egged the pudding.” We knew we would get criticism and we had to decide which one we wanted. We wanted the criticism to be, “You’re too conservative” and that’s mostly what we got. The opposite is everybody saying, “If this thing is exaggerated then maybe the whole thing is exaggerated.” Then your methodology comes under suspicion. The data is consistent, conservative, and transparent and we source every data point.

I think people feel helpless about global warming unless big government is on board.

It’s the other way around. Not one single solution depends on big government except maybe nuclear power, which I do not support personally. One of the mistakes we constantly make is to think that if big government gets it then everything is going to be okay. Big government doesn’t really figure out solutions. Reversing global warming is not going to happen from the top down or the bottom up. It is a middle-out phenomenon. There’s almost nothing government can do except be intelligent and support the solutions of individual companies, organizations, farmers. And obviously make changes to our tax policy. Stop subsidizing what we don’t want and subsidize what we do want, which is what taxes are supposed to do. Right now subsidies are upside down and backwards.

You are one of the people who put the notion of socially responsible business on the map. The implication is that business is part of the solution.

We can’t achieve drawdown if some people get it and other people don’t care. This has to be pretty much a universal goal and understanding. It has to be ubiquitous. So of course businesses have to do it. Small, medium-sized, supersized—virtually every company has to commit. Suppliers, farmers, cities, buildings and maintenance, and schools—you name it. This idea that somehow someone else is going to get it done while we lead our lives isn’t true. And consumers need to do it too. Beyond changing one’s diet, an individual can leverage and influence something to accelerate most of the solutions in Drawdown—buying from vendors that employ regenerative agriculture, for example.

You started your business career with a little natural products distribution company called Erewhon. Can you trace the arc of your ventures?

Erewhon started in 1966. I took over a little food co-op in Boston that was doing $25 a day. Seven years later we had about 35,000 acres of organic food under contract, three stores, 3,000 wholesale accounts and a railcar and a five-story warehouse. It was the beginning of the natural food movement in the United States back when little was going on. Erewhon is now in LA and I think people would agree that it’s the best whole foods store in the world. That DNA of Erewhon has been carried forth rather beautifully by its owners.

Then there was Smith & Hawken, which started out as an Ecology Action center in Palo Alto that had been selling gardening tools for intensive gardening. At one point the tool supplier in Ohio had a flood and went belly up so I paid for a container of new tools and that’s how Smith & Hawken got started. It grew to be fairly large.

Then I started OneSun Solar, which is now in India and Italy and which makes lightweight solar panels for people who can’t afford a $300 or $400 panel. It’s thinner than a yoga mat and costs only $30, designed so that you can nail it to your cottage wall—different from the big, rigid, crystalline glass silicone-based panels that most people see. There’s a few others I got involved with but that’s my entrepreneurial experience.

You’ve been amazingly prescient with all these trends, whether in business or your social and environmental activism. To what do you attribute your ability to tap into the zeitgeist of important changes?

For some reason every once in a while I feel like I can see around the corner and get a glimpse of where things are going and how people will change. I think many people do that, by the way. That’s really what an entrepreneur does—looks at things and creates a product or service that converges with people’s needs and interests in the future. That’s EntrpreneurialismIf it converges and grows it’s successful. If not it fails. For me it was more like, “How am I changing? What are my legitimate needs that aren’t being met or addressed by society or the business world?” It was obvious in 1966 in terms of food quality and supermarkets and processed food. I mean it was ridiculous what “food” had become in the United States.

It‘s wonderful to see how your environmental reflexes and your entrepreneurial reflexes have interwoven. Was making money a strong motivation?

No, it never has been. I know people who have done very well financially and accomplished their dreams. But as I said at the outset I was much more interested in learning than financial accumulation. Right now big commercial companies are snapping up brands in the natural products industry because their own brands are failing. Had I stayed in the industry I might be wealthy but I didn’t. We’re only here for a short time so accumulating capital never seemed satisfying. I wanted to do as much as I could for others in a way that is not about accumulation. I am not in any way criticizing that. I’m just describing who I am.

What was it like working with Martin Luther King, Jr.?

At 17 I was just a gawker. I worked with his staff as the press coordinator for the March on Montgomery. We all did our work then, but later it turns out to be the historic march from Selma to Montgomery. Never did I think it was going to be as historic as it turned out to be. It was extraordinary. I’m the luckiest guy in the world to have been near to people like MLK and David Brower. Oh my gosh.

Who were other influences?

My dad was a photographer so I was around people like Minor White, Brett Weston, and Imogene Cunningham. He was photographing other people’s art for their portfolios, so I was around Peter Voulkos, and many other artists and folksingers. I worked at CORE as a photographer so I met James Farmer. I don’t want to lionize myself because I was the fly on the wall. As a photographer I was in Meridian, Mississippi, after the three civil rights workers were tortured and murdered. I was assaulted and almost kidnapped by the Ku Klux Klan. Thus I got to experience the world in a way that was pretty amazing. I’m grateful for the civil rights part because I was able to see human ignorance manifest as hate in a vivid and awful way. It helps me understand conflicts, like what happened in Ireland and Rwanda, and what we now see in the Middle East, the sectarian insanity of the Shia-Sunni conflict where they’re blowing each other up. It gave me an understanding of how human beings can devolve. People come to look at some group as other and so therefore you can do what you want to them—rape the women and kill the children. I went to Kosovo as a journalist and interviewed hundreds of survivors of the Serb atrocities.

So for me having been around artists and seeing the world in all its glory and awfulness was really helpful. I think art in general is much more open to the span and breadth of the human dilemma—as is science. We tend to think of science as objective data and facts, but no—you can’t understand science without imagination. It’s our spirituality, too. It creates a sense of interconnectedness, which is what spiritual life or spiritual practice does. How does life work? I don’t think we know but not knowing means you take very good care of it because you don’t know what you’re helping or harming. It brings so much humility.

From this metaphysical perspective it raises the question, is climate change happening to us or for us?

That inquiry comes from The Work of Byron Katie and reminds us that how we look at challenges determines who we are and how we live our lives. If something is happening to us we act as the unfair victims of something. Then we point fingers and and blame. It’s harsh on ourselves actually. When we change the preposition from to to for then you realize it’s actually a gift. By taking 100% responsibility you move to innovation, creativity, and imagination and a different way of being in the world.

It’s the nature of systems to give feedback. If you break out in a rash and have a fever, that’s your body giving feedback. If you listen and respond to your body’s feedback then it leads to better health. Global warming is a blessing, not a curse. Global warming is feedback from a very complex system called the atmosphere. If responded to properly that feedback will lead to a far better transformed world than the one we live in now. Any system or organization that denies and ignores feedback perishes and dies. So we should be grateful for the feedback as opposed to cursing it or blaming it or wishing it didn’t happen.

Don’t you ever succumb to fear? Are you afraid?

Once I gave a talk in Phoenix to a big business audience. The person interviewing me asked, “Are you hopeful?” And I said, “No, not at all,” and the whole audience broke into this nervous laughter. After talking about all the possibilities for reversing global warming, then to say, “I’m not interested in hope. At all … ” As I see it, hope is the pretty mask of fear. There is no such thing as hope unless you have a fear.

I’m interested in fearlessness, not hopefulness. But am I fearless? Actually, no. I’m just a human being. Fear is basically the past projected onto the future. If the past is about regrets and depression and sadness, then the future is about fear and apprehension. They’re manifestations of each other. I think we have to stop using fear to motivate people about global warming. It turns people off and makes them numb.

26,000 acres of virgin forest, possibly containing the most diverse biome in the world.

What delights you in life?

Serving it. I mean from my little nuthatches in the garden to this work at Drawdown which is so fascinating.

What ticks you off?

Me. [long pause] I’m just hard on myself. I’m not recommending it to anyone but that’s just where I am.

Can you give a final message to Common Ground readers who have followed you and are fundamentally interested?

Yes. If ever in our life there was a common ground this is it. Global warming and climate subsumes food, water, security, energy, habitat, housing, human rights. Everything we do, touch, and know is impacted, affected, determined, and modified by climatic stability or instability. This is the common ground we share. There is only one atmosphere and only one Earth and they are interactive. They create each other. We are the ones who need to get in alignment with how life works. In that alignment there’s being, transcendence, good work, meaning, and the understanding of why we’re here at all. Some people think the most important question is “What will you remember and hold dear when you die?” I think the most important question to ask is “Why are you alive?” Because to answer that question you have to reflect on what life is and that is where beauty, love, poetry, science, reverence, and compassion all arise. Why did we come here?

Rob Sidon is editor in chief and publisher of Common Ground.