Taking the Arrow From the Heart

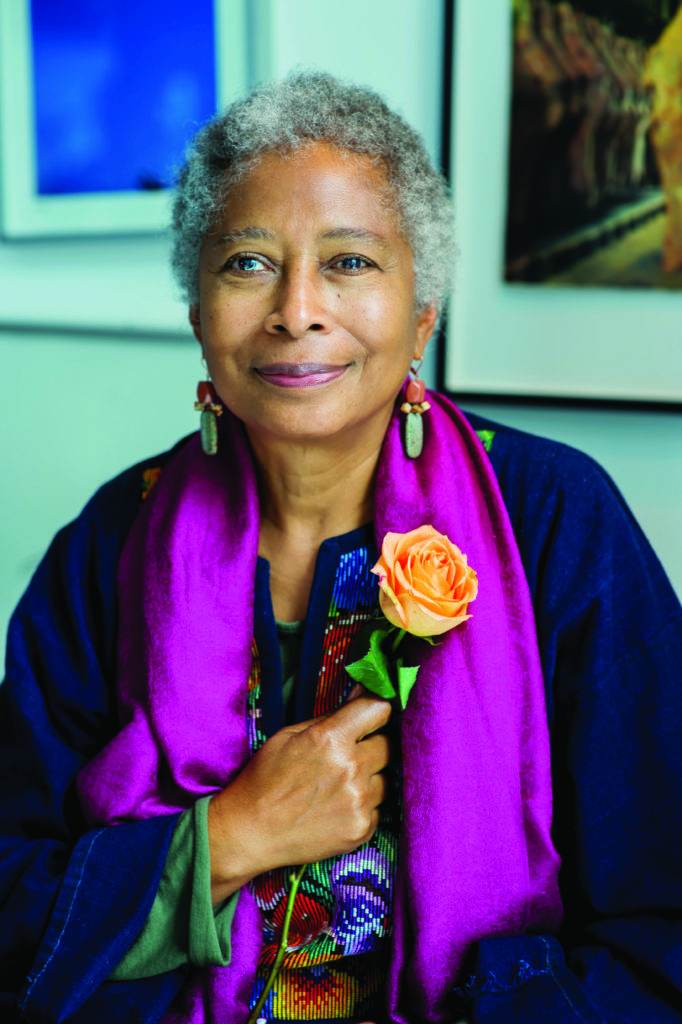

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker is a novelist, short story writer, poet, and activist born in 1944, the youngest of eight children of sharecropper parents in Eatonton, Georgia. As an 8-year-old she was blinded in one eye while playing cowboys and Indians, which prompted her interest in reading and writing. She was valedictorian of her high school class, earning a scholarship to Spelman College, where she met the likes of Martin Luther King and Howard Zinn. In 1963 she transferred to Sarah Lawrence College, where she became pregnant and had an abortion—an experience that led to a bout of suicidal thoughts that inspired Once, her first published collection of poetry.

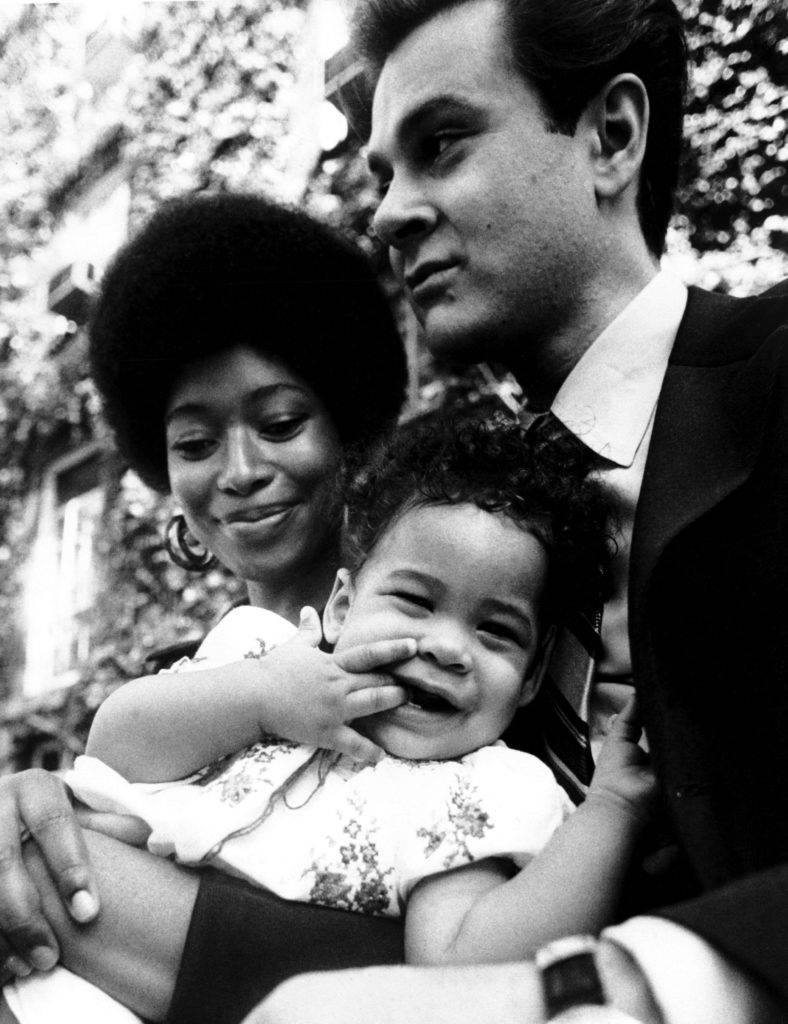

In 1967 she married Melvyn Leventhal, a Jewish civil rights lawyer. They settled in Jackson, Mississippi, where they were harassed and threatened by whites, including the Ku Klux Klan, despite becoming the first legally married interracial couple in the state. In 1969 Alice bore their daughter, Rebecca; the couple divorced amicably in 1976. Alice and Rebecca have long been estranged.

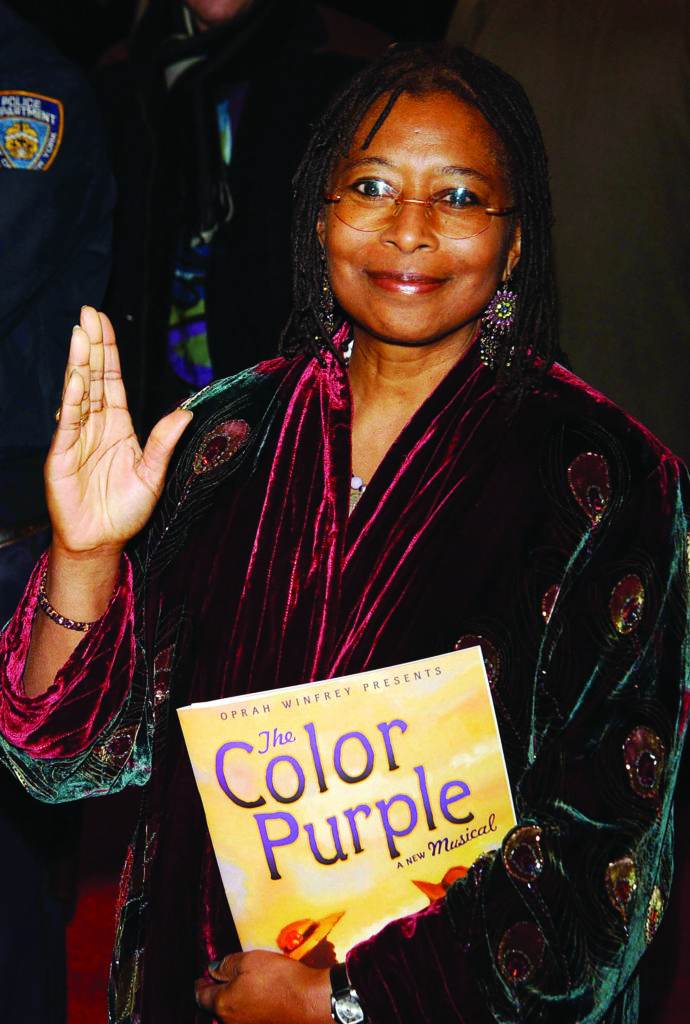

In 1982 Walker won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for her novel The Color Purple, which was made into a Steven Spielberg hit movie in 1985 featuring Whoopi Goldberg, Danny Glover, and Oprah Winfrey. The novel and film generated painful criticism from black groups who denounced the portrayal of blacks, but the controversy died down by the time the story was adapted into a Broadway musical in 2005.

An avowed feminist who early on taught college courses on black women writers and became editor of Ms. Magazine in 1973, Walker in 1983 coined the term “womanist”—to mean “a black feminist or feminist of color.” Walker claimed “womanism…a word of our own” to unite women of color with the feminist movement.

A leading figure in liberal politics who participated in the early Civil Rights and anti-war movements, Walker was also part of the female activist group Code Pink, which traveled to Gaza in 2009 in response to the Gaza War. In 2012, she refused to authorize a Hebrew translation of her book The Color Purple, criticizing Israel as an “apartheid state.”

The author of numerous novels and poetry collections including Hard Times Require Furious Dancing and Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart, Alice, a longtime Bay Area resident, is the subject of film director Pratibha Parbar’s Beauty in Truth.

Common Ground: The world is transfixed by the Supreme Court nomination hearings, which feel like the Civil War since they represent a challenge to Roe v. Wade. What’s your sentiment, especially since you personally experienced having an abortion in college?

I think that it’s every woman’s right to control her body. If you’re not ready to have a baby, you should not have one. I have had two abortions in my life and they were done because I realized I could not afford to keep anybody’s children, mine or anybody else’s. My mother had eight children but never wanted to have eight. She wanted to have six. I was the eighth child. One of the things I learned was how it feels to really know that your parents do love you but that they really wish you hadn’t been born.

I think that people should realize that half of the people who are born on the planet are accidents—unplanned. It’s cruel to make people suffer for something that was an accident, in that they didn’t plan to have a baby. They thought they were just having a wonderful experience. So I don’t think there’s a place for the judges or anyone to insert themselves. Grownups pretty much know what they need and want. If they don’t want to have another child, they shouldn’t be forced to have one.

How would you convey this sentiment if you were trying to sway an audience of female conservatives?

I have no idea. All I can do is talk out of my own experience.

You’ve spoken about this universal wisdom of women, as I understand it, in the context of tempering the male impulse to destroy. Can you elaborate?

I think you’re referring to a talk I gave about indigenous people in the Southern Hemisphere and I am forgetting the name [of the culture] but they understood men’s and women’s different tendencies in the role of creation. They had the idea that women’s role was to create and men’s role to destroy—but women had the power to say when to stop. The men in the culture were supposed to heed the warning from the women as to when to stop their destructiveness.

We don’t have that. And this is one of the things that indigenous people, especially the ones from deep indigenous-rooted cultures, find so strange about our culture: The men just destroy and waste and pollute and the women never say “Stop.” Now if the women try to say stop, nobody pays much attention. Our lack of balance is really obvious to people who have lived in cultures where things are more balanced and where there’s a deeper understanding that you cannot just continue to trash the planet without limits.

Going back to the Supreme Court—it’s been a very cruel court for most of its existence. I can’t claim high reverence for it as it has made us grovel to get even tiny freedoms. Then it has delighted in snatching those away whenever somebody with a lot of money or power could force somebody on the Supreme Court to basically make us feel like idiots for believing that we could have a country where everybody could more or less be free if they left other people in peace.

You were very active in both the Civil Rights movement and the women’s movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s. What difference did you see between those movements?

The Civil Rights movement started in the South but it’s heavily African American. The leaders were African American people, mostly men but a lot of women leaders behind the scenes. The women’s movement in this country was mostly white, especially in the beginning, but in other parts of the world of course it wasn’t—which is what people tend to forget. We tend to think that it started here but all over the world women have been struggling to be free—being pro-abortion and opposed to brutality from the husbands and men. The women’s struggle is not so new. It’s just that it found a voice in the ‘60s and ‘70s and a coalescence. In the West we have a greater ability to project the happenings.

You knew Martin Luther King. What was the effect of meeting him?

We met when I was a student and he came back to Morehouse College where he went as a student. I went to Spelman for a couple years, which is a women’s college right across the street from Morehouse. He was a fully grown person in his full fierceness as a warrior—a compassionate warrior. I must’ve been a sophomore, or even a freshman, fresh-person. Anyhow he had an incredible impact on me because he seemed to be fearless. Now I don’t think that was true. We all have fear—it’s a natural thing. He had decided that his love outweighed his fear and he really loved us. He inspired us out of that love.

This is our Women’s issue so let’s talk about Mother Earth. I’ve heard you lament that the earth has been muted, that the landscape is silent, leaving an inert terrain for the likes of Monsanto to plunder.

Monsanto is just one in a long line of plunderers. I come from Georgia, in the South, where hundreds of years ago they pretty much destroyed that land. They started destroying it by cutting down all the trees and then burning all the stumps and planting cotton. That wiped out that whole ecosystem. What you see now is nothing like it was before white European people moved to this continent. That silencing of nature is the legacy—they just couldn’t stand any kind of noise.

One of the problems with our short attention span and our educational system, which is so terribly faulty, is that people have a hard time understanding that Monsanto is just the head of the beast that we’ve been dealing with for 500 years. It’s just that we’re seeing it now because it’s so stark. Not long ago we couldn’t even imagine that Western and postmodern

technology would actually start killing the immense ocean. We thought, “My God, the ocean is so huge—how could you do that?” Well, they’re doing it. It’s the murder of the planet. It’s tragic for many of us who have been trying to draw attention to the fact that it’s being stolen and killed. It’s hard for people to see it because these connections are not made. The ahistorical sense is strong. We cannot move forward in full understanding if we don’t know where we’ve been.

Long before it was in vogue you were experiencing shamanic plant medicines like Mama Ayahuasca. How did those journeys inform your Earth wisdom?

When I encountered Grandmother Ayahuasca and the teachings it was astonishing, confirming that the earth is alive. It’s conscious. I say Earth but it’s whatever else there is here—wherever it is we are—and that it’s wonderful, and right! It taught that we were living in such a magical realm that people didn’t understand.

Honestly there’s not a person you could ask the question, “Where are you?” Because who would know? Or “How did we get here?” Nobody would know. What Ayahuasca does for the person who is a real seeker is teach that this is just one realm among many endless other realms and maybe you can get a peek into some other realm if you have a guide.

But then without a guide you get lost, like Timothy Leary and those people who went down to Oaxaca. Do you know the story of how they met up with Maria Sabina?

Not really.

She was this shaman who was healing people with mushrooms. And they came with their Western way—basically just to get high and have a hallucinatory adventure, whereas she was working at the level of curing the soul and connecting it to the planet, to the earth, and to whatever other realm. There was a lot of confusion and distance from each other and inability to fully connect and feel trustful with each other—because of all the past—the disasters of missteps and of their trying to make some kind of American fun out of another culture’s deep wisdom. People have not wanted to do the hard work of actually being taught to understand another way of relating to our life support. And we’re paying the price.

Your mother raised you Christian. What was the effect on you, as a way to speak about your background?

I ran away from church when I was eleven because my parents were too tired to make me go anymore. First of all, I couldn’t understand what the preacher was saying and I don’t think he understood what he was saying. I loved the music. People were kind to me and loved me but I didn’t believe. I sat there looking out the window pretty much the whole time because to me, the church is everything — the planet, Nature. That’s where I felt at home.

So I stayed home and had a wonderful time with the elements, the wind and rain and the sky and trees. I grew up absolutely loving Nature. Now that doesn’t mean that I didn’t also love some of the really good people that were talked about in church. I really liked Jesus, a lot. I resented the idea that I had to look at somebody being tortured on the cross. I thought it was just so wrong, especially for my culture because we had enough lynched people being tortured. We didn’t need to have another. It was hard on the spirit.

Did you gravitate to Eastern spiritual philosophies? What has been the general arc of your spiritual quest?

Nature, Native American, Taoism. I feel closer probably to Taoist thought. Basically to just be quiet in Nature and to be respectful of its ways and to try to model myself more on how Nature does instead of how some out-of-balance human with too much money is doing. That has been a great saving of my life—to have these teachers.

Also Buddhist thought. Nature first. Taoism second. Buddhism third. And then there’s just my mother’s incredible radiance as a being who connected with the earth and who truly loved what it could produce by working together in Nature. That was my model for how humans — if they worked respectfully with Nature — could create incredible beauty and sustenance for humanity.

You grew up poor and became very successful. Was material success a motivator for you? Has it been satisfying?

I grew up very, very poor but I never felt incapable of securing a decent life for myself and my children, if I had children. My ambition was to have a decent life in community, not a well-to-do life. It’s true that I have done very well because I work hard and my books have sold a lot of copies and all that stuff. But I still live very simply. I still have a garden. I still have chickens and a very simple life.

I’ve heard you say that even women who do achieve a lot are still often managed by men. How was that your experience?

I’m not.

I heard you say that growing up in the South you came to expect that every white man was just like Donald Trump—that this is just how they are.

Yeah, I mean there was no way I could ever assume that they were any better than Donald Trump. I mean, how would that have happened? I didn’t know another kind existed. I didn’t know that there were decent white men until I was seventeen. The first one was Howard Zinn, and I’m so thankful. I tell you, it’s just amazing.

The irony is that you fell in love and married a white man who became the father of your daughter.

Oh, no, no, no. I didn’t even like that he was white. How dare he? I was annoyed that he was white. I fell in love with his soul and it’s not like I’m marrying a Donald Trump from Georgia. I’m marrying somebody who’s risking his life to help me have a life. There’s a big difference. At that level of being color is ridiculous. I mean color is always pretty ridiculous but really, when you’re in Mississippi and the Klan is leaving its calling card at your door and people are firebombing houses and killing people, you don’t really think that much that the somebody you like is white. You think about them as somebody that you’re really hoping will be safe.

Suffering is the great teacher. I’ve heard you speak about the glowing preciousness of life and I’ve heard you also speak about deep suffering. How do you reconcile those seemingly opposite narratives?

I reconcile them because they have to be if you expect to stay alive. A lot of people are committing suicide but I don’t plan to do that because I feel that life gives pretty much what you put into it. In my case I put all my gratitude for what I have, as life can be sometimes up and sometimes down, bountiful and whimsical. Life is both, but on balance it’s a wonderful life, even with all the suffering.

I have suffered a lot and I’ll probably suffer more but I have seen some incredible sunsets and amazing rivers. I’ve been swimming in some. I’ve met some incredible people. Endless the joy that exists here when you can clear away your own cobwebs.

Is there a fundamental message within these titles like Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart and Hard Times Require Furious Dancing?

They are their own message. Hard Times Require Furious Dancing—that’s pretty much where we are. The earth has had about as much as she can stand of us as humans who just destroy things, and so she’s sending up hurricanes and typhoons and earthquakes and whatever she can come up with. She’s sending them right in on us. And I don’t blame her, she’s put up with us for a very long time and I feel like I’ve done my part not to be damaging but I think she’s pretty sick of us.

So what can you do when times are so incredibly hard? You do all your political work, you do all your philosophical work, you do all your poetry and your novel writing. Then there’s nothing much left but to meditate and dance. The thing about hard times is that they’re so fraught with the energy of disaster that it’s a furious dance — but it is a dance.

Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart comes from a Buddhist concept that I learned from Pema Chödrön about how we are shot in the heart. Constantly now. I mean there’s always something that just gets you. And the trap would be to just keep trying to yell at the person who is doing it, like yelling at Trump, just as an example. So while you’re screaming at the archer you’re dying because you haven’t tended your own heart and learned how to take out the arrow. You could actually try to learn to do that—to take it out. Then when you have your heart open and healthy again you’ll have more energy to deal with all the incredible horror that we are all faced with now. But you can’t do it if you’re screaming at the person or situation that caused it.

I’ve heard that The Color Purple came through you like a divine download.

No, no, no, no, no, no, no. Rob, I never use that term—download. But let me just tell you. This is the brief version: I lived with my grandparents when I was 8 years old and I loved them very much. They were extraordinarily kind to me—my grandfather especially. Yet as younger people when my father was growing up my grandfather was a terrible person—and also my mother’s father. They were batterers—just terrible people. I did not understand how that was possible—that they could transform. This grandfather whom I knew as an 8-year-old, who died in the course of time, was someone I wanted to spend more time with consciously. He was a gentle, kind, thoughtful old man. So I felt like I’d been with them but I was so little and life was so tough that I didn’t understand hardly anything.

So basically that story [The Color Purple] comes out of a little 8-year-old who wanted to understand her grandparents, and her parents and her community, but who didn’t have the time. So when I had an opportunity I moved my house from New York to California and I wrote it in a year.

The Color Purple attracted so much criticism from the black community back in the day. How did that criticism affect you?

The criticism was very painful. It was undeserved. It was ignorant because most of the people had not read the book. Then they criticized the movie. But by the time it was turned into a musical there was no more criticism left, which was very interesting. A lot of those people had died, and then some of the others had children who started teaching them about sexism and wife beating and incest and all those things that now everybody knows and talks about. So it just died away.

After The Color Purple I started a publishing company [Wild Tree Press in 1984] and went to the country and published other people and went swimming in the river and kept on admiring this great creation we live in. That’s the other part of that kind of trial. You see how ridiculous it is. It hurts, and yet when you’re sitting under a redwood tree that’s 500 or 700 years old by a river that just seems really far away.

As an artist do you ever look back at novels such as The Color Purple with the decades of intervening wisdom and think, “Oh, I might re-tweak this or that”?

No, there’s no point. I don’t have time. I keep writing. I’m going forward. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen my blog but I write and publish something several times a month. I don’t feel the need to go back. I did it the best I could then. It’s true to what was, in my ability and my heart, I don’t re-tweet. [giggles] Re-tweak.

You’re coming out with a new book, sharing your personal journals. I’m curious what those will be about and why you’re moved to share them.

Well, we can talk about that when I get to that, but I’m not there yet.

What pains you most?

Abuse of the earth and of people pains me the most. I can hardly stand what is being done to children—almost everywhere. I mean poor little things. If I were a child spirit being incarnated somewhere I would go back. I wouldn’t need an abortion. I would just say “Nope, I’m not coming here.” I really would say that to almost any child spirit because we don’t deserve the children we have. We treat them badly. Even the ones who are quote “well-todo”—the rich ones—I find that they don’t have much of a life either. Maybe because they are kept separate from the reality that so much of the planet is being destroyed and that children almost everywhere have very little say in what happens to them. I mean they are really just treated abominably. That is the hardest thing.

Something that pains me is the thought of young girls undergoing female circumcision. It’s something that Eve Ensler taught me about.

That’s another whole front—the abuse of children. Children just don’t get to have a say in what is happening. It’s hard to bear.

What makes you happiest?

I’ve had a good life. With all the struggles, all the suffering, it’s been amazing. I’m so grateful. Even though the ocean is so badly polluted and the whales are dying it’s still an incredible thing. I’m glad that I lived at a time when I didn’t realize what was happening to the earth. I feel like those of us who are around this age should be very grateful that we lived here at a time when it was still solid. It was still firm under our feet. That’s a gift of huge magnitude.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.