Why Black Lives Matter

By ROB SIDON & CARRIE GROSSMAN

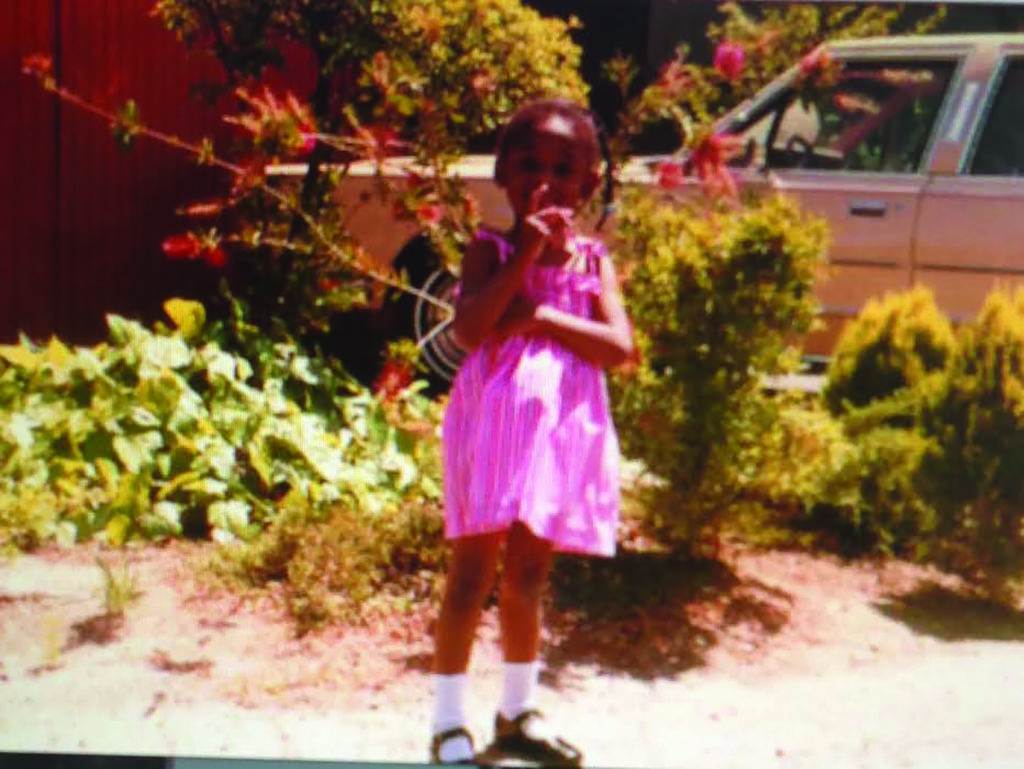

Alicia Garza was born in 1981 to a single mother in Carmel, California, and was raised in Marin County, where she identified as queer at an early age. After graduating from Redwood High School in 1998, she graduated from UC San Diego in 2002 and earlier this year earned her master’s in ethnic studies from SF State. Alicia, along with Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi, is best known as cofounder of Black Lives Matter, which emerged in response to the July 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, the year prior. Black Lives Matter has rapidly expanded to 40 chapters and is leading a phenomenon of global protests that according to Alicia have “only scratched the surface.”

Along with her responsibilities at Black Lives Matter, Alicia serves as Special Projects Director at the National Domestic Workers Alliance. During the 2016 presidential election, she was famously critical of Hillary Clinton, claiming “the Clintons use black people for votes but then don’t do anything for black communities after they’re elected. They use us for photo ops.” The recipient of numerous commendations, she lives in Oakland with her spouse, Malachi Larrabee-Garza, a trans male activist she met during a protest in San Francisco in 2003. They share a dream of getting people who believe that all lives matter to fight like hell to make sure black lives matter.

Common Ground: You’re best known as the cofounder of the Black Lives Matter movement, but how do you like to describe yourself?

Alicia Garza: I like to describe myself as the cocreator of the Black Lives Matter Network. Somewhere along the way, folks started describing Patrisse [Cullors] and myself and Opal [Tometi] as cofounders of a movement, which is an inaccurate portrayal. We created a vehicle for black people who were and are still searching for communities—political and spiritual—that value the need for blacks to be able to live dignified lives and rejoin dozens if not more other kinds of entities that also create spaces like that.

It is the relationship between all of us that makes a movement. This is important to say for a couple of reasons. One is that movements are not launched for things like hashtags. They are created by people who decide that they want to do something together and take risks together. Two, this movement has been going on for a very long time—before I was even a twinkle in my mother’s eye. Historically, it is important to understand the trajectory of movements. We are certainly blessed to be at the forefront of our generation’s iteration of this long movement, but when I describe myself I want to be really careful about not erasing other people’s contributions and not erasing how history brought us to this place.

So when I describe myself, it is as cofounder of a network that is global. We have more than 40 chapters around the world and dozens more groups that may not be formalized chapters but certainly are initiatives in solidarity and alignment with our vision and our principles. We are a part of a larger movement that has been dubbed the Black Lives Matter movement but it is really the black freedom movement, which has been in process ever since African people were enslaved and set foot on these shores.

On a personal note, can you share the story of your childhood and your upbringing?

I was born in Carmel and later moved to Marin County. My mom was a single mother who was not prepared to have me but decided to make a go of it. For my first four years she and her twin brother raised me. My mom worked during the day and my uncle at night, and they combined their incomes. It was hard for them to make ends meet—particularly for my mom as a single black woman. It’s not an easy feat to raise a child in Marin County. She faced varying levels of employment discrimination. She fought hard for me to get opportunities, such as when I taught myself to read at 3 and the schools wouldn’t take me. She convinced grade school officials to take a risk on me. Had she not known how to fight that hard, I don’t think I would’ve had the same opportunities I have had in my short life. I say short because I’m 36. I didn’t grow up sensing I lacked anything.

When I was 8 my mom married my stepdad, who is a fourth-generation San Franciscan, and they started an antiques business together, which they’ve run for 25 years. They are now getting ready to retire. When I was 8 they had my younger brother, Joey, whom I love to death. I live in Oakland; he still lives in Marin.

Was religion or spirituality important in your family?

I was raised culturally Jewish but never bat mitzvahed. My dad’s family is between culturally and religiously Jewish. We grew up observing High Holy Days but my folks were never really rigid or Orthodox. My mom comes from a religious Baptist family and converted to Judaism. My parents gave me a choice as to how deeply I wanted to engage in spiritual practices. I’m not a practicing Jew at this point in my life and consider myself a deeply spiritual person but not very religious.

What does that look like for you?

It means I believe there’s something bigger than myself and that it deserves to be acknowledged and given reverence. I think humanity can be incredibly selfish and self-centered, and it is important to acknowledge that there are forces bigger than me conspiring in my favor. If I could get out of my own way by both acknowledging their presence and giving thanks for the blessings I’ve received at every step, then my life would be even more rich. That is how I define being deeply spiritual but not religious.

You went to Redwood High School. What was your academic path thereafter?

I graduated from Redwood in 1998 and went to UC San Diego, where I double-majored in anthropology and sociology. I graduated in 2002 and moved back to the Bay Area to get more involved in organizing in my community. It’s taken me eight years but I just actually completed a master’s degree in ethnic studies. My graduation ceremony was this past May.

Do you remember first acknowledging being sexually attracted to other women, and how did coming out land with your family and in white-bread Marin County?

I had always known I was attracted to women but never knew the language for it. I feel lucky because my immediate family has always been supportive of me. Not everybody has that experience, so I feel blessed. My extended family had a much harder time. I think Marin is liberal around a lot of things and conservative around a few specific things. [Laughs] I felt more weird being the only black person in a place than being queer.

To what extent do you personally feel discriminated against and victimized?

I don’t ever feel like a victim. For those of us who are assigned those labels, we learn how to live and survive within them. I feel like a survivor of something I didn’t create and I just feel annoyed by that. [Laughs] My being a black queer woman means that those particular identities shaped my life’s chances. The work I do every day is to make sure that everybody gets a fair shot at the dreams and the future they want for themselves. The greatest consequence of racism or sexism or patriarchy or homophobia is that it limits people’s ability to live full and dignified lives. I see that as a crime against humanity.

These labels propelled you to become an activist?

What propels me is the desire for all people to be able to live full lives. I feel deeply distressed whenever I see or experience myself as a barrier to being able to achieve that. So that’s what drives me, literally, every day when I wake up in the morning. Every night when I go to sleep I think, How we can get a little bit more free?

I know you’ve done this a million times but would you mind explaining—yet again—how Black Lives Matter began?

[Laughs] I appreciate you acknowledging that I’ve told the story a million times.

Essentially, a child [Trayvon Martin] was killed in Sanford, Florida, and the adult [George Zimmerman] who murdered that child got away with it based on laws that allow people to kill other people based on their fears and those laws that are codified in our society. A short way of saying it is that Trayvon Martin was killed because he was black, and George Zimmerman got away with killing a black child because it was a black child. It’s not the first time a black person was killed in America. Black people continue to be killed in America, but that particular day when the verdict was announced that George Zimmerman was acquitted of all charges, I was enraged.

I wrote a love letter to black people on Facebook and I ended that love letter with the words “our lives matter” and “black lives matter.” My sister [Patrisse] put a hashtag in front of it and started to use the phrase on social media. Those actions catalyzed a lot of other people because it put words to what people were feeling and thinking about what it means to live in this country. My sister Opal [Tometi] helped create a social media platform that was designed to bring people together who were outraged and saddened and fearful about the fact that America—the land of the free and the home of the brave—allows this kind of thing to happen. Rather than just lament about it, we created space in the digital world for people to connect and then encouraged people to not just talk about what was happening online but to get together and do something about it in real life.

A year later Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, and was left in the streets for four and a half hours. The community of Ferguson erupted. They erupted not because it was the first time that a black person had been killed or abused by police in St. Louis or in Ferguson but because an entire community witnessed just how little their lives mattered. They began to use “black lives matter” independently of us. We put this phrase out in the world a year prior, and people were using it to describe racial relationships with a very simple statement that calls out the fact that black lives don’t actually matter in this country. The message describes what was wrong and could be right. It helped galvanize hundreds of thousands of people around the world to conflate Black Lives Matter with not just police killings but with racism in America. That is the beginning of the story, but I don’t think the full story of Black Lives Matter has been realized. The protests over black people not being valued has become a global phenomenon.

What do you consider the other accomplishments of Black Lives Matter?

Since 2015, within just a year, because of all of this attention, there were more than 40 laws passed around criminal justice reform in 2016. Black Lives Matter has certainly impacted the national debates as to who should lead this country. It has been successful electing candidates for local and state offices. It continues to galvanize the hearts and minds of people all over the world. As a movement, if we were to identify some accomplishments thus far, those would just be scratching the surface.

Is the trend of police violence up, down, or sideways over the past few years?

Police violence remains steady. What fluctuates is people’s attention and their relationship to it. In this moment there’s lots of attention being paid to the person running the country because of all the ways in which he performs, not only in terms of white supremacy, but his ideology for how he thinks the world should function. Unfortunately, in his vision many of us are problems. That’s not just about Black Lives Matter, that’s about poor people, women, queer people. He has launched a full-scale attack on the people who actually make this country great. That has changed the level of attention on police violence and police murders.

He’s even attacking professional football players. Are you in connection with Colin Kaepernick and the NFL Take a Knee movement?

We got in a relationship with Colin Kaepernick and Eric Reed as well as the other players on the 49ers who took a knee with Colin. We are also very much in conversation with some of the players who have decided to join and use their platform to raise awareness about racism and violence in the United States.

How important do you think it is that Black Lives Matter was founded by queer black women as opposed to cis male leaders like Colin?

I think it’s really important, since we offer a new perspective on what leadership should look like and include. It shakes to the core most people’s understanding of how social change happens. While we’ve made incredible progress on that, there is still a very concerted effort to find a male leader. That’s not shade at all to Colin Kaepernick, who should be applauded for the courageous stance he’s taking at the risk of his career and sometimes his safety. We should be mindful that it’s much easier for us as a country to celebrate the courage of men than it is to acknowledge the ongoing bravery of women, of queer folks, of people who are marginalized.

Hillary Clinton was a woman candidate for president. Can you explain why you weren’t on board with her?

I think that as a country we deserve more than empty promises and rhetoric and the status quo. The 2016 election was a series of miscalculations on the part of the Democratic Party about where the political pulse of the country was. The backlash to President Obama’s tenure and Black Lives Matter was very strong, so that is why we now have a president who sympathizes, empathizes, and celebrates white supremacists and white supremacy.

Another miscalculation was in generalizing the specific concerns of people of color, of women, of queer people, into a broad class agenda that doesn’t actually look at the differences in experiences of people who are closer to the bottom of the economy. We can’t just continue to talk about lifting up the middle class when the middle class is disappearing and becoming less of reality for more and more people. We can’t talk about getting Wall Street under control while those same leaders continue to capitulate to Wall Street. Those deep and obvious contradictions made it difficult to support the entire field of Democratic candidates—and I don’t think it was limited to Hillary. The entire field of Democratic candidates continued to be obtuse around racial injustice and racism. Whether you look at that from the position of being a woman or whether you look at that from the position of wanting to improve the economy, you cannot talk about either thing without talking about the impact of race on both. Both candidates were unsuccessful because the pulse of the country wanted to talk about the intersections of race and class and gender. The failure to do so allowed us to usher in a president who promises to deepen those cleavages.

Now that Trump is president, do you have any remorse? Do you think Clinton would have brought her own brand of kleptocracy?

I don’t have any remorse about the way that I acted. I voted for Bernie in the primaries and for Hillary in the general. The question of who should be remorseful should be placed squarely at the feet of both Hillary and Bernie, to be 100% honest. It is unconscionable in 2017 to continue to tell black people to put our concerns aside around racism so that other things can be addressed. We cannot continue to throw black people under the bus in favor of women’s liberation or in favor of getting closer to the middle class these things cannot be separated. The huge elephant in the room is race. I don’t have any regrets and I don’t think that Black Lives Matter has any regrets. We participated very actively in the political process and refused to give our endorsement to candidates that did not adequately acknowledge the traditions we’re living in.

Do I think Hillary would’ve been a klepto-crat? The Clinton way of leading has always been from the center. That got us welfare reform that devastated the lives of millions of Americans. It got us private prisons that lock up and contain more than two million people. To be fair, it has also gotten us different ideas around how we improve the lives of women and how to close the wage gap. The challenge of trying to lead from the center is that you give away a lot of things you don’t need to give away. So would Hillary have been like Trump? No, absolutely not. Trump is leading the decline of the United States in rapid form. We should all be terrified about his agenda and what it will do to all of us. Would Hillary have been a better president? Sure. Does that erase the concerns that I just raised? No, absolutely not.

Obama was the first black president. Why were you critical of him?

Just because you have a black person leading the country, it doesn’t necessarily translate to black people’s concerns being addressed directly. Similarly, just having a woman president doesn’t mean that the political power of women is increased. Representation is not power. What we saw under President Obama was a lot of good things and a lot of challenging things. One major challenge we saw was the rate of deportation. Under his leadership more people were deported than under any other president in history. We should take that very seriously. While being proud that a black person was elected to the highest office in the land, I would be silly to not be critical of that.

My major criticism of Obama is that he was not strong enough on addressing racial inequality and the impacts of structural racism. He did inherit a whole lot of challenges but his refusal to deal with this big elephant in the room created a whole series of other challenges that we are still grappling with. Some of his accomplishments included making sure that millions of Americans who would not have otherwise had healthcare had healthcare. A lot of people, including some Republicans, are waking up to both how challenging it is to figure out how to take care of everyone and the importance of what it means to take care of everyone. That is partially why they haven’t been able to dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

Another thing that Obama did that was important and significant was he presided over the release of more than 7,000 people from prisons and jails for nonviolent drug offenses. That was a very important step toward not just reforming the criminal justice system but literally reuniting people with their families who never should have been gone from them in the first place. Obama had a lot of accomplishments but his challenge was not being aggressive enough in addressing racial inequities.

Don’t you think Obama oversaw a radical shift on gay marriage?

It sounds like you think that, which is not a question but a statement of what you think I think. If you’re asking me what I think, I think Obama had to be pressured to oversee such a shift, and I’m glad that he ended up on the right side of history.

Harriet Tubman is said to be your patron saint. Can you remind readers what Harriet did in her life and say why you admire her so much?

Harriet Tubman was a suffragist, an abolitionist, and a community builder. She helped build the underground railroad, which essentially freed enslaved people from bondage. She also fought very hard for the rights of women—specifically black women—to participate in our society. What inspires me about her is her tenacity, her ferocity, and her clarity of vision and purpose.

What’s your opinion of Oprah Winfrey, a 21st-century kingmaker who is a black woman?

Oprah is great. She does a lot of great stuff and she’s an inspiration to a lot of people.

Has Oprah expressed affinity with Black Lives Matter?

Yes and no. She’s compared Black Lives Matter with the activism of her generation and has asked us where the leaders are, to which we’ve replied, “All around you.” There is not one leader of a movement. Dr. King was a great leader but he was not the only leader of his time. There were hundreds that made that period of civil rights what it was. So my sense is that Oprah is supportive of Black Lives Matter, and it’s possible that she may not totally understand the power of this movement and its adaptations of old forms for new circumstances.

Angela Davis is another one of your heroes, right?

She absolutely is.

Your critics attack you for being a Marxist. Do you identify that way? What’s been the effect of that?

I think what is fascinating about our country is that we assign and attach labels to ideas that are threatening to the status quo. What I say is that I identify as someone who believes very deeply that every person should be able to live a full and dignified life. Throughout history, people who believe that way have been called witches or subversives. They’ve been burned at the stake. There’s a ton of labels that have been attached to people like me who believe that everyone’s life is valuable. You’re always going to have critics, but what’s more important to me is that we are able to build the biggest team possible that can help us achieve those goals of ensuring that every single person has the right to live a full and dignified life.

It’s ironic that conservatives align so adamantly with Christianity yet Jesus’ words and actions, if studied, would earn him the Commie label. What does real democracy look like to you?

It looks like full participation in the decisions that impact our lives. Democracy, if it is to work, requires that everyone participate but it doesn’t mean that everyone has to participate in the same way. Everyone must have the opportunity to shape their own circumstances and life outcomes with a commitment to ensuring that what works for one person doesn’t negatively impact another.

What’s your vision for true “allyship”? Do you really think the privileged can operate in solidarity with those who are marginalized?

Again, this is somewhat of a leading question. I don’t have a vision for allyship because I don’t believe in allies. Allies are people who say they agree with you but don’t make a commitment to tearing down the barriers that keep you from living a dignified life. That’s why I don’t have a use for allies. I don’t want to be agreed with. I want to be supported in tearing down the barriers that prevent me and millions of other people from living full and dignified lives. That means I need co-conspirators—people with whom there is a commitment and a practice that conspires against the systems of white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism, and the like. The choice to operate in solidarity with those who are marginalized has always been in the hands of the privileged. Whether or not that becomes realized is up to those who are privileged and powerful at the expense of others.

The yoga community is well intentioned but predominantly upscale and white. How do you recommend such privileged communities reach across the aisle?

I don’t recommend that the yoga community reach across the aisle. I recommend that the yoga community eliminate the aisle.

In an interview you said “protest has become a commodity.” What do you mean by that? Is this akin to what occurred in the sixties, where capitalists cashed in on the counterculture?

When I say that protest has become a commodity, what I mean is that activism has become trendy, but the outcomes of activism are still contested. Protest has become a brand when in fact protest is a tactic that is used to interrupt bad things from happening. Protest is popular now as long as it’s not inconvenient and as long as it doesn’t challenge the structures that operate a divided and unequal society. I wasn’t alive during the sixties, but I know there was a lot more happening than the counterculture. People were fighting for their lives and fighting for the right to live dignified lives and make decisions over their lives. “Tuning in and dropping out” at its best was resistance to a set of cultural norms, but it was not in and of itself a fight for people’s lives. At its worst it was a way for a largely white audience to participate without participating in being a part of the changes that were necessary to realize a new way of life.

What is the poem written on your chest?

It is a poem by June Jordan, “A Poem About My Rights.”

What brings you joy?

What brings me joy is knowing that there are infinite possibilities for freedom. My community brings me joy. My work brings me joy as well.

How do you combat fear?

Fear is a natural part of taking risks. If you’re not afraid, you’re not doing it right. Rather than combat fear, I acknowledge its existence and then I keep going. One foot in front of the other, focused on my purpose and what I am called to do.

Do you think that Black Lives Matter has been co-opted by similar movements such as Brown Lives Matter or All Lives Matter? What’s at stake?

I wrote about this in my piece called “A Herstory of the Black Lives Matter Movement” in the Feminist Wire, so I won’t spend a lot of time reviewing this. It’s not helpful to replace “black” with something else. Of course all lives matter—in theory. But in practice, black lives in particular are facing deplorable conditions at every level. If you believe all lives matter, then you’ll fight like hell to make sure that black lives matter.

What final message do you want to share with Common Ground readers?

It’s so important that all of us roll up our sleeves and do the work needed to make this country, our communities, and our world, more equitable. We cannot do that if we don’t do the hard work to eliminate structural racism. I hope that all of Common Ground’s readers will join the movement to do just that.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground and Carrie Grossman is its senior editor.