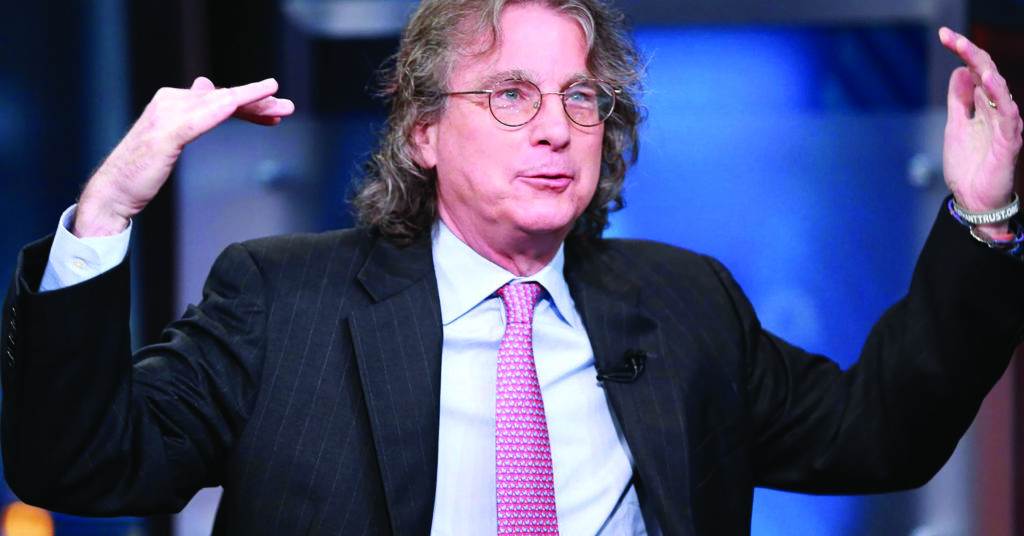

Roger McNamee, Tech Insider Turns Whistleblower

Roger McNamee was born in 1956 into a large family in Albany, NY. Severely ill as a child, he learned to be a quiet observer—a skill that proved helpful when he grew up to become a tech investor. Also a self-taught guitar layer (Moonalice, the Flying Other Brothers), he found that his musicianship gained him camaraderie in the nascent PC industry when he started as a T. Rowe Price analyst. He went on to co-found Integral Capital Partners, Silver Lake Partners, and Elevation Partners, the last with U2 singer Bono. With an uncanny prescience he succeeded as an early investor in many big companies including Google and Facebook, and became an early mentor to Mark Zuckerberg.

In early 2016 he formed a hunch that bad actors had been using Facebook and other platforms for dark purposes. He learned more about social media’s profitable dirty little secrets—including “brain hacking” and “filter bubbles”—designed to create unhealthy addictions. Though a longtime Silicon Valley insider, he admits to being caught off guard by technology’s potential dark side and has since been on a whistle-blowing crusade to do the right thing. After seeing McNamee on Fox News’s Tucker Carlson Show, we invited him to be our interviewee for the magazine’s Love issue, particularly as his revelations aim to protect defenseless children.

Since 1983 Roger has been married to music theorist Ann McNamee, who co-wrote “It’s 4:20 Somewhere,” which has smashed all records for independent downloads—nearly 5 million and counting. Together Roger and Ann support the Haight Arts Center, Wikimedia, and the Tembo elephant preserve, among other projects.

Common Ground: You succeeded as an early investor in some very successful disruptive companies such as Google and Facebook. Now you’re sounding the alarm, particularly as it relates to children. What’s your message?

Roger McNamee: Those of us who have lived in Silicon Valley over the last 30 or 40 years got accustomed to the notion that the technologies we were producing were making the world a better place. For decades that was actually true. Technology optimism made us blind. So many years of positive outcomes caused us to be complacent and not recognize that one day there would be a dark side.

My message today is simple: The combination of social media products, advertising business models, and smart phones has produced unacceptable risks for society, particularly for children. There’s nothing wrong with social media per se. The problem is that the advertising business models create incentives to addict users in the pursuit of attention, which is the fuel that drives profits.

The largest social media platforms are competing for attention on a scale that we have never seen in media before. The techniques used by firms like Facebook and Google and Snapchat and YouTube result in surveillance operations that would be the envy of any intelligence service. They know more about us than we know about ourselves and certainly more than the government. They track us everywhere we go on the Web. And in the case of Google and Facebook, they track us to some places we go off the Web. There would be no harm if they weren’t then using what they learn to maximize their profits by manipulating what we think to make the advertising more valuable.

Can you explain the term “brain hacking”?

Brain hacking has several elements. First, a media company appeals to low-level emotions such as anger and fear as a way to stimulate our lizard brain. This increases engagement. They combine this with a series of other techniques, techniques in many cases borrowed from the casino gambling industry that are designed to get you coming back. If you look at Facebook notifications they’re a perfect example. Notifications do not come to you uniformly. They’re what is known as a variable reward. Variable rewards are at the heart of the design of one-armed bandits and other casino gambling tools. Similarly every pixel on the screen is designed to engage your reaction and get you to come back with increased frequency to drive profitability.

The last element of brain hacking is filter bubbles. Facebook, Google, and others show you “what you like,” reinforcing pre-existing beliefs, making them more rigid, and ultimately preventing you from being able to accept ideas that are not consistent with those preexisting beliefs. In that state, it is really easy for the platform or third parties to plant ideas in your head that you think are your own, including ideas that are demonstrably false. My estimate is that one-third or more of Americans are victims of brain hacking . . . and almost no one knows it.

Can you tell the story of how you met Mark Zuckerberg and became an early mentor?

In March 2006 Chris Kelly, who was the chief privacy officer at Facebook, asked me to take a meeting with his boss but would not tell me why. Mark came to my office and we sat in a conference room, just the two of us. I said, “Mark, we haven’t met. Before we start I need to tell you a couple things so you know where I stand before you tell me anything.” I took two minutes to say, “If it hasn’t already happened, Yahoo or Microsoft is going to offer $1 billion for your company. Your family, your executive team, your board of directors, and your employees are all going to tell you to take the money. Your lead investor is going to tell you that he’s going to back your next startup and that you can change the world again. I’m here to tell you that I disagree. I believe Facebook is the most important company in Silicon Valley since Google.”

Keep in mind that at that time they had approximately $9 million in total sales and maybe 100 or 150 employees. I said, “If you believe in your vision you have to go for it. The real truth is that great startups require both an idea and perfect timing. You may have another great idea. Lots of people have a second great idea. The thing that you can’t control is perfect timing—it is very rare and I don’t think it’ll happen to you. I’ve never seen it happen to anyone.”

What followed was the most painful silence of my entire life. It lasted somewhere between three and five minutes, but it seemed like hours. My fingers were white knuckling. Imagine waiting while a guy runs through a series of “Thinker” poses with thought bubbles twirling above his head. Finally he relaxes and says, “You’re not going to believe this.” I said, “Try me.” He said, “I have a contract to buy the company for $1 billion from one of those two companies. And every single thing that you predicted is happening. How did you do that?” I said, “That is what happens in Silicon Valley.”

So cool.

He said, “What do I do about it?” I said, “Do you want to sell the company? He said, “No, but I don’t want to disappoint everybody.” I said, “You won’t disappoint them. This is a really great idea. If you go out and make it work, they’re going to be a lot happier than if you sold.” It took us less than five minutes to figure out how to stop the deal. It turns out he had a golden vote he could decide without anybody else’s approval. With that I became one of his mentors. For the next four years we interacted a lot. There were issues with a few executives because the team was so young. There was a magazine exposé related to the Winkelvoss brothers. In the early days of the smart phone I was convinced that mobile was going to take over everything and he needed a strategy for it. I was just one of many voices on that issue but we spent a lot of time on that.

Didn’t you introduce him to Sheryl Sandberg?

In late 2009 it was clear that the company needed to develop a business model but there were no direct analogs. I thought the closest was Google and I was very close to Sheryl, as she introduced me to my business partner, Bono, and her brother-in-law worked with me first at Silver Lake and then at Elevation. I played an indirect role in her going to Google so she was like extended family to me. Sheryl was suspicious of going to work for somebody that young but when I introduced the two of them they got along and one thing led to another. Sheryl joined the firm as the chief operating officer. At that point my role at Facebook was done.

Sheryl is one of the most capable business people I’ve ever encountered and that list includes people like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett. She had been a longtime advocate for women in executive and workplace situations. thought it was a really cool thing that she was going to become the creator of Facebook’s business model. I had no idea then that they were going to lose control and wind up where we are today. Their goal was to bring the world together, not tear it apart. They did not think of what they were doing as brain hacking. They did not ever contemplate that bad actors would take the tools they had created for legitimate advertisers and use them to harm the powerless.

How did you first become aware?

In February 2016 I saw memes coming from Facebook groups that were ostensibly connected to the Bernie Sanders campaign but they were deeply misogynistic and in some cases even worse than that. I was thinking to myself, “There’s no way Sanders’ campaign would do things like that.” Yet these memes were spreading virally with incredible intensity, which meant that somehow people I knew were being lured into these groups and they were sharing the memes. I didn’t know what it meant but I thought to myself, “This is a really bad thing.” Then in June came Brexit, and I finally realized that the Facebook platform carries these emotional appeals to fear and anger and xenophobia with so much potency in the algorithms that it created an asymmetry. Negative campaigns had a chilling advantage over neutral campaigns or positive campaigns when it came to the audience reach per dollar spent on Facebook.

I discovered later that it is possible to use Facebook to implant ideas in people’s heads. Fake news is not the actual problem. It’s a symptom of a bigger problem: “filter bubbles.” By showing only things you like, Facebook creates the illusion that everyone agrees with you. Over time, pre-existing beliefs are reinforced and become more extreme. Platforms like Facebook are designed to stimulate the lizard brain and trigger dopamine surges, which make people more susceptible to manipulation. Like brainwashing, brain hacking is the notion that if you have someone in a position where their defenses are down you can implant something. That essentially makes them into a different person than they would have been in the absence of this technology.

We saw this with things like the Pizzagate conspiracy theory and the false news story that the Pope endorsed Trump. We’ve see it on the left, too—it’s not like any particular group has a predisposition one way or the other; we all like having our biases confirmed. What people don’t realize is they didn’t originate those ideas. Those ideas were planted by somebody else and that somebody else planted them for their own profit. Again that somebody is not Facebook, that somebody is not Google. It’s people using the tools of Facebook and Google to implant ideas and profit from them. Facebook and Google are the arms merchants in that scenario.

Now you’re the whistleblower calling out the dirty little secret. Why this crusade?

I think it’s the right thing to do. As you can imagine, appealing to those low-level emotions is not necessarily consistent with the wellbeing of society and this is particularly dangerous for children, who have no defense against psychological manipulation. You see this most tellingly in products like YouTube Kids and Snapchat, where, in the case of YouTube Kids, there has been an epidemic of age-inappropriate content. In the cases of Snapchat and Instagram, there are psychological challenges created by the fear of missing out where kids see that all their friends are somewhere that they are not and it crushes their self-esteem. It becomes a form of bullying. The incredible thing is that the world got addicted to these products without being aware of the dark side.

This is not the first time that has happened. After World War II there was a massive change in Americans’ eating habits. Before the war people ate meals with ingredients they cooked at home. After the war convenience became a priority and we saw the rise of packaged foods and TV dinners. Convenience was compelling to people working hard to raise kids. What we did not realize until maybe 30 or 40 years later was that convenience had a cost. These foods were loaded with sugar, salt, and fat, which triggered an obesity epidemic that has now reached crisis levels.

With social media there is an analogous problem. We embraced convenience and we embraced it for free. We got huge value up front, the same way we did with prepared foods. But we were slow to recognize the cost. We were slow to recognize that convenience came with psychological penalties that in extreme cases includes loss of agency. Threequarters of Americans use Facebook, most of them every day. More than 62% of Americans get their news from Facebook, whose advertising model does not exist to make Americans happier, healthier, or more successful. In a world of brain hacking and filter bubbles it appears that everyone agrees with you and that’s obviously dangerous for democracy. In Facebook’s case this amounts to two billion individualized channels, one for every user on the first universal content delivery platform—the smart phone. It’s as if each user has his or her own Truman Show.

What happened when you spoke out?

In October 2016 I went to Mark and Sheryl with my concerns about the platform, including things relating to the election but also in other sectors. For example, people were scraping the names of Facebook users interested in Black Lives Matter and selling them to police departments in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Another example is that Facebook’s tools enabled discrimination against people based on race or religion in violation of the Fair Housing Act.

I put together a framework with seven examples and took it to them. I expected them to be reluctant to accept it. They were working like crazy and getting all this positive feedback from users and the stock market. When everyone says, “You’re the coolest thing that ever happened” and then some dude you used to know really well comes in and says, “Wait a minute, I think there’s a dark side and it’s a threat to civilization,” your first reaction will probably be “Hey, Roger’s lost it.”

From their point of view I must have looked crazy. I’m thinking, “Gosh, I’m Jimmy Stewart in an Alfred Hitchcock movie. Nobody believes me because nobody ever believes Cassandra.” The election happened 10 days later, at which point I went nuts. I went, “Okay, guys, quit fucking around, this is really a bad thing.” They were incredibly polite, saying that what I had seen were anomalies—that they were not systemic. They’re saying, “We are a platform, not a media company. We are so large, inevitably a few bad things are going to happen, but we’re not legally responsible for that.”

And I’m trying to point out to them, “Guys, you can assert this as much as you want but if your users disagree then the whole ballgame is going to be different. If they decide you’re wrong your brand is going to be destroyed. People are going to abandon the platform.” I thought it would be a better strategy to get ahead of it, to consider a different business model, a way to be less dependent on advertising, a way to be less dependent on brain hacking. Apparently that message remained inconceivable to them at the end of 2016 because it has been reported that when President Obama talked to Mark Zuckerberg in late November 2016, Mark’s reaction was to dismiss his concerns. In fact, the day after the election Mark was on a panel at a conference where he characterized the notion that they had influence the election as “crazy.”

I understand how they got there. It must have been really hard to internalize the bad news through the first part of 2017. By late summer of 2017 the evidence was incontrovertible, yet Facebook continued to treat this as a public relations problem, not as a systemic issue related to the business model. That was when we realized we had to build public awareness of the problem and encourage people to talk to their friends. We needed to help Congress understand that even if they answered the question of “Did the Trump campaign collude with the Russians at Trump Tower in June 2016?” we would still be faced with a persistent threat to elections from manipulation of social media. The Russians had been using platforms like Reddit and 4Chan to create conspiracy theories. Then using Twitter to get press exposure. And then blowing them out to the whole population over Facebook. It was incredibly clever. They used the tools in Facebook precisely as they were designed to be used, but for an objective that Facebook would never have approved had they known what was going on. But because everything at Facebook is automated, they didn’t know it was going on. And it never occurred to our intelligence agencies that a foreign power would use American technology to hack into the brains of our voters to affect democracy.

You’re cracking a major story. You have this gift of prescience and for understanding and predicting trends. Where does that come from?

To the extent that I’ve been able to see trends early, I haven’t always been able to get the full benefit because of the limitations of my ability to communicate. I read a lot of history and fiction. History helps you understand that most things have happened before, so you can learn from others’ experience. Fiction teaches a lot about how humans feel and how relationships work. You learn how to read people. I’m the second youngest child in a huge family. I had a lot of health issues as a kid. The result was that I was a quiet kid, speaking little, observing a lot. When I develop an insight about where the world is going, it often takes me longer to be able to articulate it in a way other people can understand. For example, when I first had the opportunity to invest in Facebook, I was unable to convince my partners that this was the game-changing company it would become.

I have an awful lot of limitations. In the early days of Facebook I knew there would come a time when Zuck would outgrow me and they would need a different kind of mentoring because I’m not an operations guy. I’ve been successful as an investor in spite of my personality. I’m not driven by money or wild ambition. I like the game. I like trying to understand the puzzle of how human beings adapt over time, how we evolve. I think of myself as a real-time anthropologist. I look at what’s been going on in society and then I spend a lot of time thinking about what the possibilities are for the near future, understanding the relative tradeoffs among them and then using Occam’s razor to arrive at what the likely path is. I’ve always thought out what the alternative paths could be. When I’m proven wrong, which I am often, I’ve already had time to think about what I would do instead. Graceful recoveries from errors have been the hallmark of my investing career.

Isn’t art—music—your first love? Tech investing has been your day job, no?

Tech investing is a day job. Let’s not be confused, I love the game. I loved the people of the personal computer industry, some of whom led the early days of the Internet. When I arrived in the personal computer industry I was so lucky. People assume I must be smart, but the reality is that I have been unbelievably lucky. I began my career on the first day of the bull market of 1982 and they assigned me to cover tech, a sector that essentially had a headwind for the first five or six years and has had a tailwind ever since. Good luck overwhelms everything else.

Because of music and the demographics of the PC business I had an easy entry. I’m approximately the same age as Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, and all those people. Basically the PC industry was created by people born in 1955 and 1956. These weren’t like old-fashioned industries where at trade shows people went to bars or strip clubs. In the evening all these nerds would get together and have jam sessions. The problem was, hardly anybody knew more than a few songs all the way through. Because I had been playing happy hours forever, I knew a couple hundred songs from beginning to end. I had some charts so everybody could sing along. The way the sociology of the PC industry worked was that if you knew enough music you were accepted. The fact that I wasn’t an engineer and wasn’t actually working at a tech company was irrelevant. They embraced me.

At T. Rowe Price, where I started my career, they let me develop a new model of being an analyst. I essentially traveled like a guitar-playing gypsy in a caravan called the personal computer industry. In the process I developed great relationships and learned about how products were created. I learned to tell the difference between a product that was likely to be successful and one that was not. It was a radical idea at the time but it worked. Everyone else focused on spreadsheets. I thought of myself as just a dude that was hanging around the PC industry doing the things everyone else was doing. Because we were all Deadheads it was a really fun time.

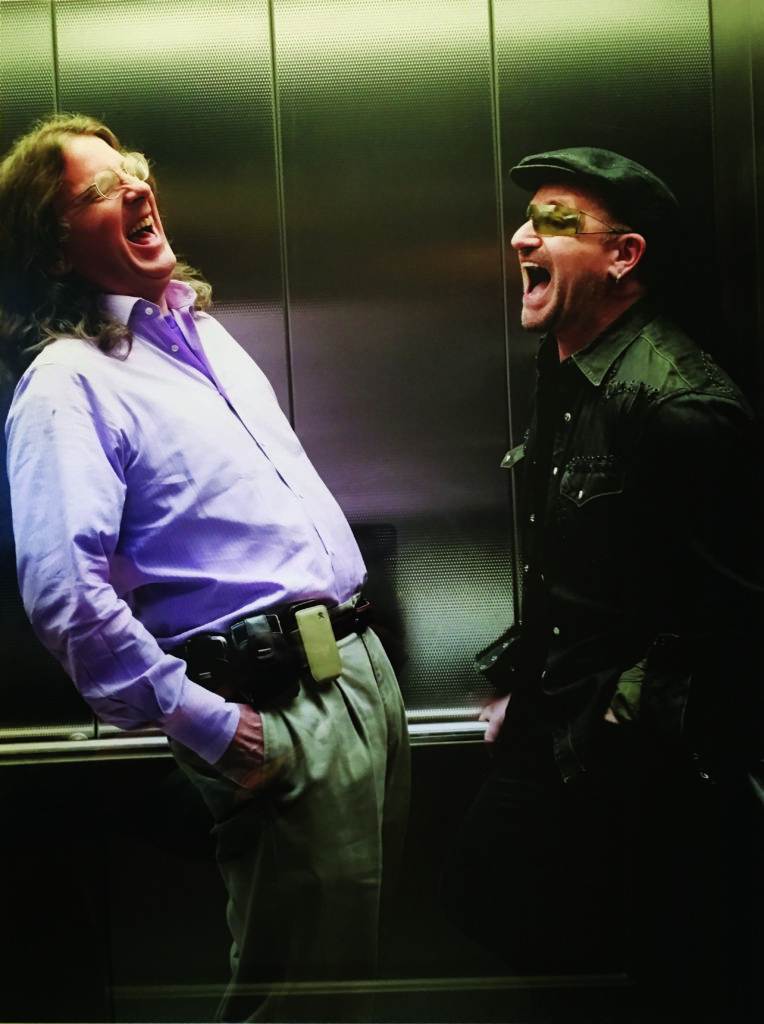

Why did you invite Bono to become a co-founder of Elevation Partners?

I didn’t invite Bono. Elevation was Bono’s idea. Here’s the background: In 1997 when I realized that the Internet was going to create a bubble that would eventually crash, I started a business plan for Silver Lake Partners, a different kind of fund that would be impervious to a bear market. It would allow our investors to not lose all their money. Silver Lake was launched in ‘99 and made its first investments just as the market rolled over. In 2001, I had a health crisis and lost a year, during which my partners realized this firm was going to be a big success and maybe they didn’t need me. When I came back in 2002 with an opportunity to make a giant investment in Apple just after they shipped the first iPod—my partners turned it down. I was stunned. I asked, “How can you turn this down?”

Then at about the same time Bono called because he wanted to buy Universal Music. So we took a look and I brought the opportunity to Silver Lake. My partners said, “We’d love to do that deal. But you can’t work on it. In fact we don’t want you here at all.” They had figured out that with the success of that first fund they could vote me out and just divide it all three ways instead of four. You can imagine that that was an ugly day and I was depressed. I happened to be in our New York office and said “Guys, I quit”—which shows you that I’m not a business guy, because I could’ve held them up for a big pile of money or threatened to go public and stopped them in their tracks. But that never occurred to me. Instead, I said to myself, “Screw this. I’m out of here.”

I called Bono and said, “I just quit.” He responded, “Well, screw them. We’re going to start our own business.” He said, “I want to be in the fund management business with you. I want to start a new fund and I want to do the thing you do, which is technology and media. We’re going to make something really great.” He added, “It’ll be really good for my Africa work.” He said, “I get all my money from people who are serious businesspeople and they view me as a rock star. If I were your partner and we had a successful fund they would take me more seriously and they’d give me more money to support my work in Africa.”

I spent the next four months putting together Elevation Partners, where Bono was going to be a real partner, not a hood ornament. He was going to be part of meetings, part of fundraising. He’s a strategic thinker and a great motivator. He was also an effective partner. He really understands the dynamics of a partnership because that’s what U2 is. They’re an equal partnership of four people. Bono is one of those guys—you look at him and go, “I wonder what he’s like at home?” And the answer is, “He’s even better at home than he is in public.” He married his high school sweetheart, he’s got four amazing kids, he’s the greatest father and he’s just a beautiful human being. Honest to God, when I first met him I couldn’t name one of his songs, but I am lucky and blessed to be his partner for over a dozen years and his friend forever.

Your wife is also a musician and part of your bands.

Ann has a PhD from Yale in music theory and spent 21 years in the music department at Swarthmore College, where she was chair of the department for at least a decade. Right before I had the strokes that resulted in my missing a year, she retired from Swarthmore. When I recovered we played music together, first in the Flying Other Brothers and then Moon alice. She stopped playing in the band to focus on musical theater and has a show in development called “Other World”—the goal is to take it to Broadway.

Ann and I met at Yale. She was a really young PhD candidate and I was an old undergraduate. Our first date? The Jerry Garcia Band at the University of New Haven gym on February 16, 1980. Ann joined me for the Dead’s spring tour. When we went to our first baseball game, she scored balls and strikes while I went to the bathroom. That is when I knew we were going to be happy for the rest of our lives. That was the best insight I ever had.

One piece of advice for men: marry up! Marry someone who brings out the best in you. Ann and I have shared an amazing adventure. There have been ups and downs in our professional lives but every day she is my perfect partner. I thank my lucky stars that Ann said “Yes.” She is the best person I know.

She co-wrote Moonalice’s biggest hit, “It’s 4:20 Somewhere.” Doesn’t that have the most independent downloads of all time?

Amazingly, 4.6 million downloads from our website in six years. The Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame couldn’t find any record of anyone making it even to 100,000 downloads off their own site. In three different years we got half a million downloads just in the month of April.

Why were you such a big proponent of Prop. 64?

For me Prop. 64 was a civil rights issue. If we enforced the drug laws uniformly it would’ve been a different animal but we used them as a form of Jim Crow. I saw a statistic that said people of color were incarcerated at three times their rate of usage. I once met a man who told me how he got busted along with 44 other people for conspiracy to distribute, which I think is 5+ years in the federal penitentiary. Forty-four people went to the federal penitentiary but he did not. You know what the difference was? Forty-four of them were black. That story absolutely convinced me that Prop. 64 was a moral imperative. My parents were very active in the civil rights movement in the ’60s. In my family the big three were Franklin Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, and Jackie Robinson. I met Jackie, which was pretty cool.

What was it like growing up?

I grew up in Albany in a very large family where I was the second youngest. I had a bunch of health issues growing up including a severe trauma at age 10 that almost killed me. As a result I had an unusual but very happy childhood. I was a very quiet, introverted kid because of a condition that prevented me from eating the same things as my classmates. No birthday cakes, no cookies, no nothing like that. I got comfortable being different and that turned out to be great preparation for my career.

My parents were beautiful, loving people and my older siblings helped raise me. I was a child of the ‘60s, super active politically. I joined my first political campaign at age 12, working every day during the New York primary for Gene McCarthy. I volunteered for McGovern in October 1971 and I worked 13 months right through the general election. I wasn’t particularly good academically, but I did these other things that colleges thought were interesting. When I applied to Yale the fact that I had been a deputy office manager in the first McGovern office in the country carried some weight.

Was music important in your family?

My sister was a professional musician. I got of to a slow start because my first piano teacher had, shall we say, inappropriate tendencies toward young boys. That soured me on formal lessons. Other than singing in the choir, I dropped out of music because of that bad experience. Then at 17, I decided to learn to play guitar. I’m self-taught for the most part.

What did your dad do?

He was trained as a lawyer and did the law for a while and then came to Albany because his father-in-law offered him the opportunity to take over a little brokerage business. By the time he got there the business had been dismantled so my father had to start his own entrepreneurial thing, which he did. It was never hugely successful but it had enough good years to put a lot of kids through college. He died at the same time I took a year off after my sophomore year. He died during a really bad time for the business, so my mother was left more or less penniless and had to sell the family house. There was no money to go to college so I stayed out another couple years to earn what I needed to finish. I was economically independent fairly young, which turned out to be tremendous preparation for adulthood.

So you knew the effect of pennilessness.

I’ve completely lived it. It was foundational to me—having my father die when I was out on my own. I had gone to California with $400 in my pocket, enough to last for one month. It worked out. If it hadn’t worked it would’ve been a shitty experience.

Is Silicon Valley purely cutthroat?

No. Silicon Valley is really different from when I started. I’m not a good fit for it anymore. It really is about money and power now. It didn’t used to be that way. I don’t interact with it the way I used to. I had two choices: I could either walk away gracefully or eventually be shown the door. I decided to walk away gracefully. If I am lucky this weirdness will pass and one day I will be able to go back.

Are you familiar with the book Brotopia, about Silicon Valley excess?

Absolutely. The author, Emily Chang, is a friend of mine and an exceptional journalist. She is doing an extraordinary service. Silicon Valley has an extreme form of a problem we have nationwide, which is that we fail to recognize that we harm our economy by not giving women a chance to lead it. We’ve run the experiment with men being in charge and look where it’s gotten us—wholesale corruption. I’ve been married to an amazing person for 34 years. My best friends have always been women. There’s nothing cooler than a really smart, capable woman. I’ve been blessed to have been surrounded by them—my mother, my sisters, my wife, my friends.

What was your mom into?

She was born in 1920, a week after women got the right to vote. She was a reporter until she had children and then she was really into Bryn Mawr, which is where she went to college. She was dedicated to women’s education and political activism and was just a great human being.

Did you have a spiritual or religious upbringing at all?

My parents had a mixed marriage. My father was Roman Catholic and my mother was Presbyterian. Her parents wouldn’t give her a wedding because she married an Irish Catholic. The Catholic Church insisted the children be raised Catholic. On many Sundays I would go to Catholic mass with my father and then the Presbyterian service with my mother, and then sing in the Episcopal choir. By the time I was 14 I was done with organized religion. That’s the end of that story.

I am a big believer in love. Love your neighbor. Love strangers. Try not to judge others. Let them live the life they choose. Help people in need. I try to treat everyone as an equal. I try to hold myself to the highest standards I can imagine.

Can you share a parting message for Common Ground readers?

My father always told me to be the best Roger I could be. That message of love has inspired me my whole life. Every day I ask myself, “Am I being the best Roger I can be?” I judge that by my own standards and by the standards my father gave me. It’s worked for me and it might work for you.

Rob Sidon is editor-in-chief and publisher of Common Ground.