Chuck and Sue Kesey’s 60-Year (Probiotic) Partnership

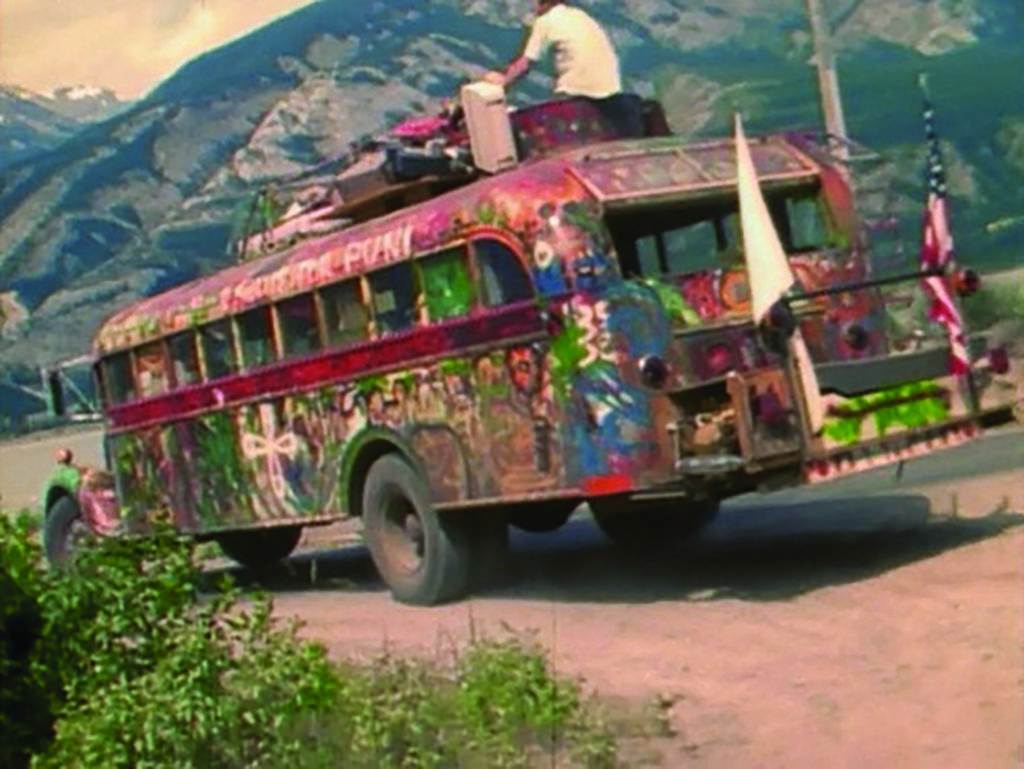

Chuck and Sue Kesey met on a blind date as freshmen at Oregon State in 1956. Thereafter inseparable, they married and started Springfield Creamery after graduation in 1960. Chuck’s novelist brother, Ken Kesey, who wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion, famously led the Merry Pranksters on the virgin Further bus ride to New York in 1964. Chuck was on board. Sue, who was pregnant with their son Kit, stayed home with toddler Sheryl but later flew to join the freewheeling Pranksters—notably Neal Cassady—as they beset Gotham’s literary elite and set the groundwork for the ensuing hippie movement. The brothers remained very close until Ken’s death in 2001. In his younger days, Ken is said to have worked at the Creamery when he needed money.

At Oregon State, Chuck was fortunate to study with some of the leading minds in the nascent field of probiotics. Intent on introducing Lactobacillus acidophilus into the human food supply chain, Chuck finally got his chance while tinkering with recipes with company bookkeeper Nancy Hamren as the creamery transitioned to making a newfound hippie food, yogurt—Nancy’s Yogurt, to be precise. Acidophilus soon became a mainstream ingredient in the U.S. yogurt making process, and Nancy and the Keseys have long actively championed probiotics as a health boon.

In 1972 financial challenges befell the Creamery and the Grateful Dead were summoned to perform an emergency bail-out concert that not only saved the company but also cemented the connection between the Dead and the fabled Oregon Country Fair, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. The musical connection between the Keseys and the Bay Area continued as the then unknown Huey Lewis distributed Nancy’s Yogurt as a day job before becoming a star. Lewis allegedly wrote “Working for Living” while making yogurt deliveries.

As early natural products pioneers, Chuck and Sue have long been in the vanguard of market trends and humorously helped sustain the industry’s founding artisanal spirit. They have steadfastly resisted the trend of corporate consolidation—keepin’ it real and all in the family.

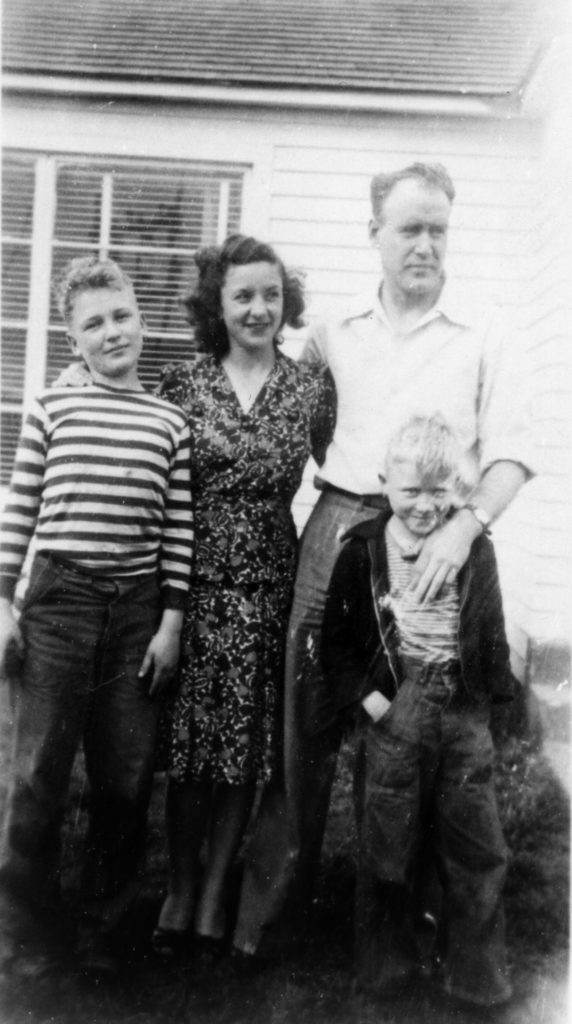

Common Ground: So 60 years ago, you two not only got married but also started Springfield Creamery. Whole lotta love! How did you meet?

Sue Kesey: [laughs] It was a blind date. We were freshmen in college and there was a spring dance coming up. One of the ladies in my dorm had met Chuck and knew he was looking for a date. She said I’d be perfect for him. He showed up at my door in this big boat of a car in his ROTC uniform.

Chuck Kesey: Yeah, had to take ROTC back then. It was a 1952 DeSoto convertible.

SK: It was kinda jaw-dropping. The car, the handsome young man with a lot more hair than he has now [laughs]—the ROTC uniform. He was funny and he was fun to talk to. Then we went out again and never looked back. Just kind of hung out with each other. When I met his family it felt like I’d known them forever.

CK: My dad put her to the test and took us on a hike to the bottom of Steens Mountain at the Little Blitzen River Gorge. Nobody goes there. It’s got great fishing but it’s a trek. I remember it took us eight hours to walk out.

SK: Not many people do it but they’d done it before. I think Ken and Faye were with us too. I can’t remember, but it was a test to see if I could walk down and back and be tough enough to join the family.

Ken was your only sibling. What was it like growing up together?

CK: Every weekend my dad planned an adventure. No matter what grade we were in, we fished every creek and every river and clumb very mountain in Oregon. And we hit it over and over and over again. We walked to the end of the world.

Were you also a wrestler?

CK: Yeah, I’ve done a lot of wrestling. My son was a wrestler. My son-in-law was a wrestler and a coach. My grandkids were wrestlers. We’ve got state champion credentials.

What is it about wrestling and the Kesey family?

CK: Wrestling is a family sport. It is a funny sport—very inherited. If you don’t have a family backing you up, you will have a hard time making it. When I go to a wrestling match I see the kids and the fathers and the grandfathers and the uncles. It’s a tough sport. Making weight was a big deal and that means that you’re dieting. That means you’re very conscious of what you’re eating. This throws wrestlers into health food immediately. You don’t waste any food and you’re constantly worried about eating the right thing.

Were you ever drawn to literature like your brother or are your temperaments so different?

CK: I’m more in the world of science and he’s the more in the world of literature. He didn’t believe in science as much as I did, but we understood each other’s viewpoint rather well. When he ran out of money he would work at the creamery [laughs]. He was that close.

Your brother was at the bleeding edge of the hippie scene with all the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Tests. How did you relate to that?

CK: Before hippies was the Beat generation. Ken immediately went to San Francisco and looked at the champions of the Beat generation and went right through that. We knew a lot of those guys and that was an evolution into the hippie generation. I watched it happen. I watched Ken in it. Both Beat and hippie—these are negative words put out by the media to make it not look very good. Hippie actually comes from the Chinese heroin dopesters who would drop to their hip—they couldn’t get off their hip. That is where the word comes from.

I never heard that.

CK: I had a hard time keeping up with Ken, I can tell you that. He pushed us into that other world of social change. You could see the change with Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and the bus. I was on the virgin ride traversing America to New York, which was risky scary business. Nothing like that had ever been done. And this was right when the cops had learned that they could arrest hippies rather easily—and out comes the bus. They just didn’t know what to do with it. They would stop it every time they got a chance. We were way ahead of the psychedelic movement, which didn’t have much to do with ours, going across America on the bus. The psychedelic hippie movement attempted to imitate the bus movement but it’s hard to imitate something.

Sue, were you together on the bus?

SK: This was 1964. Sheryl was two and I was pregnant with Kit so I didn’t ride across the country. I did fly over and join them in New York and meet Viking Press and Jack Kerouac and Ginsberg and all of the superstars and look at their world. We went to the World’s Fair, which was great.

What’s story of coming off the bus into New York?

CK: We went to a meeting at Viking with Sterling Ward, who was Ken’s agent. And there were all of the literary superstars in this apartment overlooking New York. It looked they owned New York. They were drinking wine and listening to classic music and in came the bus with fifteen people who had been riding across America. We wanted to play. We wanted to jump up and down and run around. They wanted to listen to classic music and talk philosophically. And I just saw that—whoops—just like that I saw literature change right there as Neal Cassady blew in like a wind-up energy ball. They just didn’t know what to think. This was a very off-scale literary happening.

From what I’ve heard Neal Cassady always left an unforgettable impression.

CK: Neal Cassady was the bus driver, who changed the tires, the chains. He was an unbelievable phenomenon. He was perfectly capable of talking at 100 miles an hour and not stopping. One time he drove across America in an old 1950 car in 60 hours, by himself, nonstop. He never stopped, never slept all the way across. That’s who Neal Cassady was.

Was there a family religion growing up?

CK: When you’re a little kid it was every day—“I pledge allegiance to the flag”—you had to do that every morning. My folks were Southern so that meant getting into the Southern Baptist world, and how this carries through into the world of relationship. This is why Ken takes LSD. It’s about “What’s going on in there? Let me see the truth. Let’s get down to it.”

Where in the South?

CK: Arkansas Ozarks. From the distance of things I got to see clearly into the reality of America. From the distance of things I got to see clearly into the reality of America through the eyes of my Grandma Smith. When I was little she’d go into long detail about her childhood and I’d grill her on it mercilessly. My dad migrated from Texas to Colorado and walked with the covered wagons. He met my mom in La Junta, Colorado, in a creamery and that’s where Ken and I were born. We lived in Colorado until the war broke out. Dad was in the service and we were moved to California when I was in first grade. After the war, instead of going back to La Junta, Daddy took jobs in Oregon bouncing through the creamery business as a cheese maker, butter maker, ice cream maker. My grandfather had already come to Oregon. He was a farmer who worked as a sharecropper. He never owned a house, never owned any land, never owned anything.

You’re the originators of the probiotic movement. How did you come to be the first to put acidophilus in yogurt?

SK: At Oregon State University in his core studies in dairy science and microbiology Chuck was fortunate enough to be there with professors who were bringing this to the forefront. They understood acidophilus from the veterinary side of things because it had been used for treating calves for scours [livestock diarrhea] for ages.

Yogurt was relatively unknown in the ’60s. Why do you think it was adopted as a hippie food?

CK: Food trends come and go but it was inevitable because the probiotics are really important genetically in how to make a good, healthy human being. You couldn’t keep it down and it’s still getting bigger. The good bacteria produced by lactobacillus are more than you can produce yourself.

SK: You can call it hippie food, I call it the Food Revolution. It was people looking to change the world. Part of that change happened with changing what they were eating. We were in the right place at the right time with the right product and the right connections to make this move to introducing yogurt. Chuck said, “We’re gonna put acidophilus in it because it is what people want.”

Now it’s mainstream.

CK: I knew that if you ate lactobacillus acidophilus, that you didn’t have so many diseases, that your inflammation was lower, and you could live considerably longer. It was pretty rare to understand the world of probiotics back then and it’s still rather mystifying in the medical world right now.

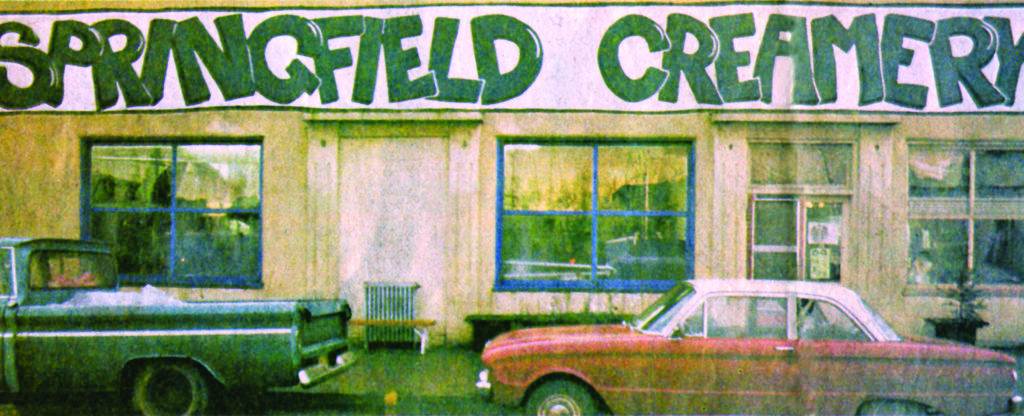

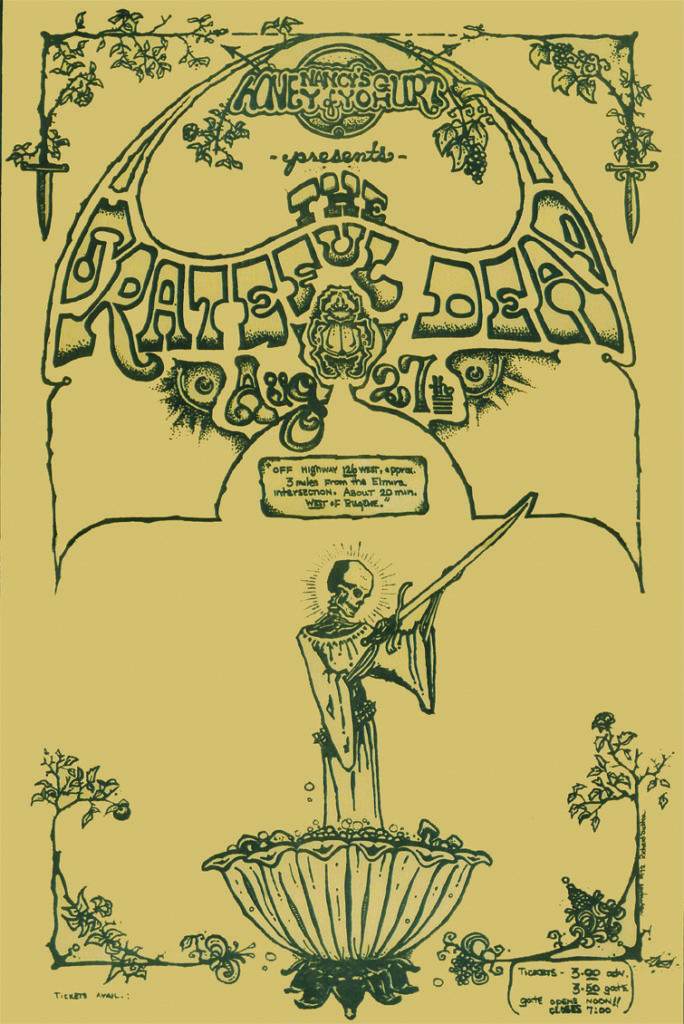

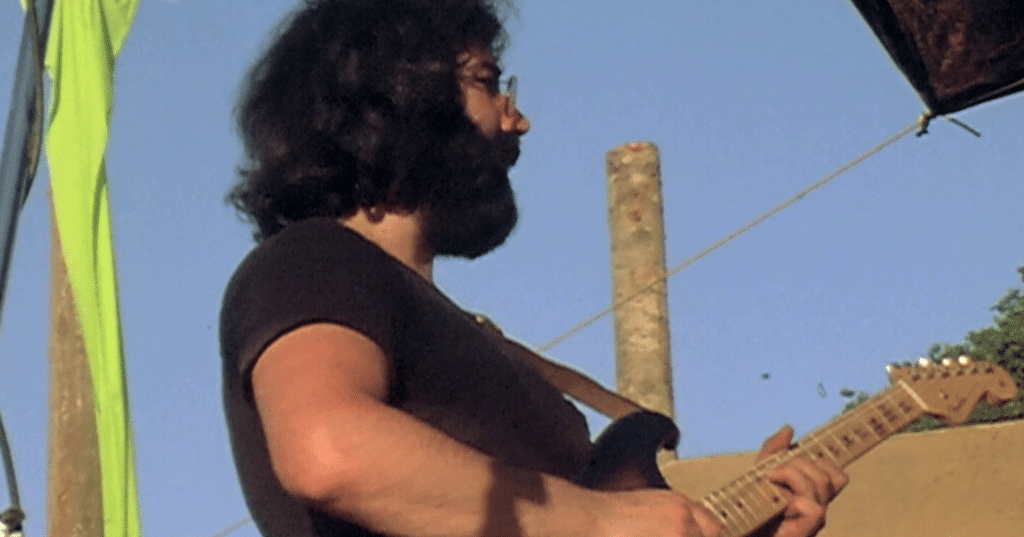

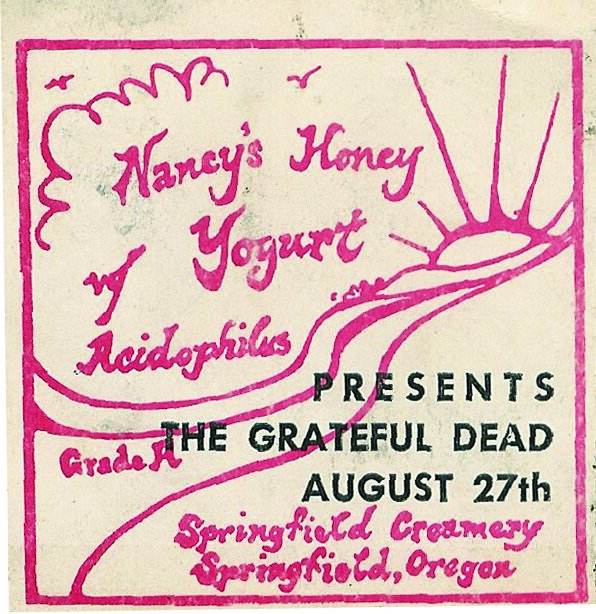

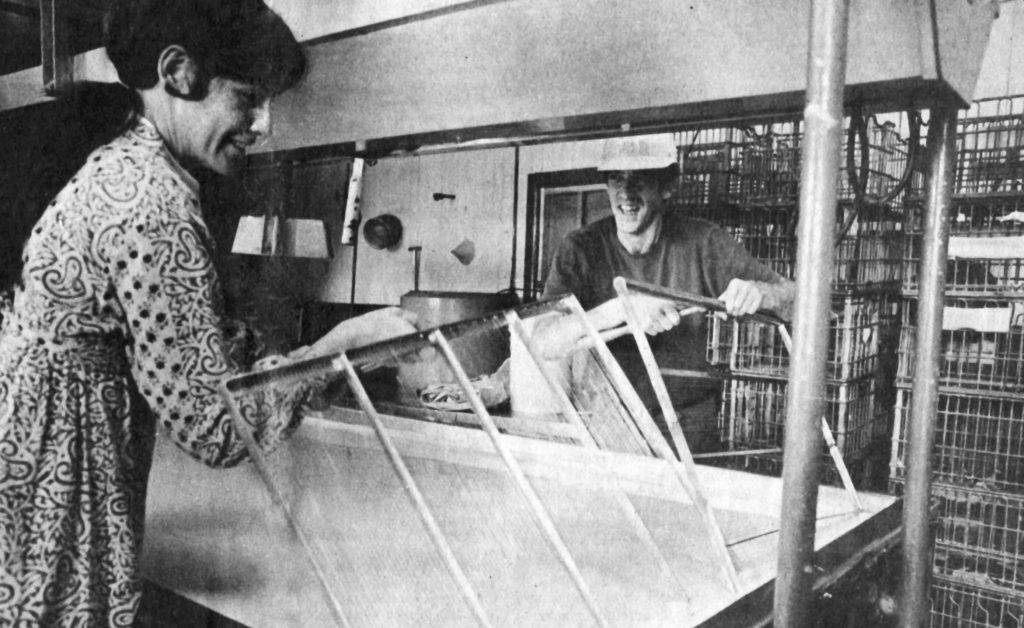

Clockwise from top: Springfield Creamery circa

1977; Jerry Garcia, Veneta, OR, 1972 benefit

concert ; the ticket and poster for the event

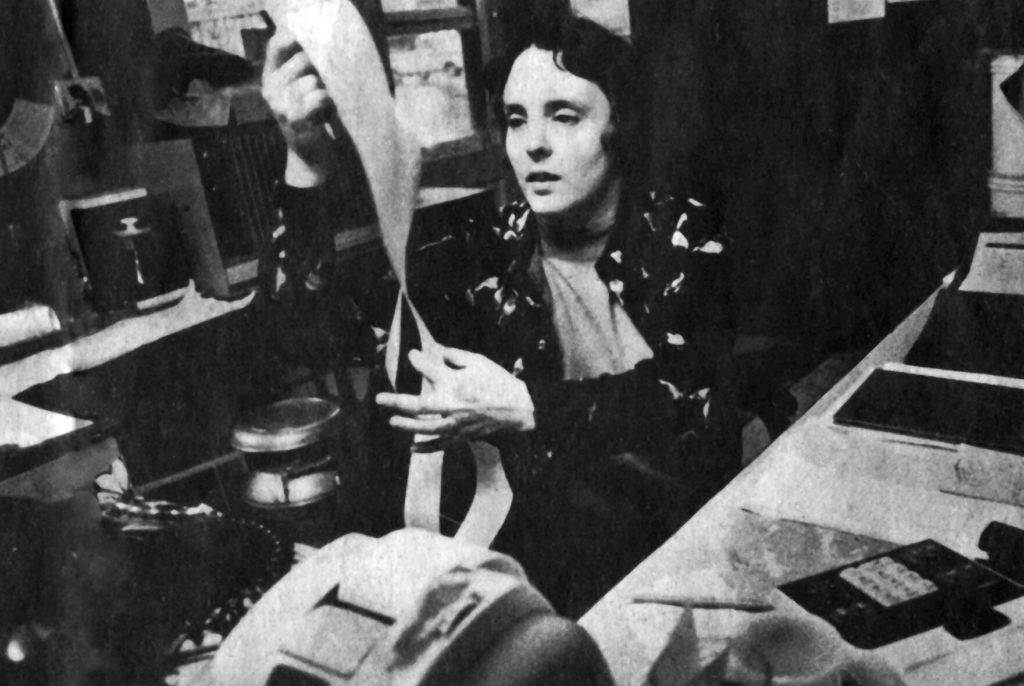

Can you tell the story of how Nancy came to be the namesake?

SK: Nancy Hamren came from San Francisco and had come to work as our wonderful bookkeeper. She and her grandmother had made yogurt for a long time. She even had a yogurt formula. It was originally a terrible formula but she and Chuck worked together and it went from there. Nancy was answering the phone in the office and taking orders from these new little fledgling coop stores and natural food stores that were popping up all over. Nancy was selling the yogurt over the phone and Springfield Creamery yogurt didn’t sound good. Chuck didn’t want his name on the product so it just became Nancy’s Yogurt.

Before yogurt we had a nine-year run doing just milk and glass bottling. We did hundreds and hundreds of bottles and gallon jugs be cause we had the only creamery that could do glass. We had a bottle washer and did milk for schools and milk for co-pack.

Nancy worked for us full time for 44 years and still comes in for an afternoon a week or two to help out in the office. It’s been a great run as healthy yogurt was exactly the right thing we needed to hang our hat on to stay independent. Nancy is still active on the International Probiotics Association board of directors. She is knowledgeable and always hungry to learn new things and is still part of our group.

In 1972 the Creamery nearly went belly up. Can you tell the story about the day a rock band saved a yogurt company?

SK: We had just converted in 1970 from doing milk to making yogurt and didn’t have much money to do it with. There was no big influx of investors or anything financing this. It was pretty tight and we needed money so the only people we knew who could generate money were the Grateful Dead. Chuck asked if maybe they’d do a benefit concert.

So you drove down to Marin County and just pleaded your case, and how did that go? I’m just curious. Do you remember that day?

CK: I drove down to Marin County and well, that was just normal business, but we knew Ramrod [Lawrence Shurtliff] pretty well. He was the head roadie and he later become the president of the Grateful Dead. And we knew Jerry Garcia so we had a lot of avenues to get a yes. Then we had to rent a field and build a stage. This was before concerts. There wasn’t much to copy. It was the biggest concert ever at that time in Oregon and it was outdoors in a field. And we had 15,000 – 20,000 people.

SK: It was challenging but it all came off and became ultimately the classic concert that the film Sunshine Daydream came from. We faced the stage west for an afternoon concert, which meant we just about baked the band because the sun was in their eyes and putting their guitars out of tune and so forth. Because it was a really hot day, over a hundred degrees.

CK: Hundred and seven. We thought we’d make money but after all the trouble we didn’t make any money. The Grateful Dead are really good guys. I think they gave us 10,000 dollars at the end of it and that got us through the financial hump. The tickets were only three dollars. That was a mistake but that was Ken’s number.

For Deadheads this is considered a monumental show. What are some of your other recollections?

CK: It was hot and everybody but the Grateful Dead said this was the nekkidest concert they’d ever been to. Nobody knew how much water it would take to put on a concert. No body had a clue. We had a water truck to squirt the crowd and fortunately I went to jump on the truck just before because someone hadn’t moved the water truck. I realized it wasn’t a water truck—it was a sewage truck. That was nuts! They’d grabbed the wrong truck. They were one minute away from squirting the crowd with the sewage. That woudda done it!

This is underground stuff but supposedly the 31-minute “Dark Star” recording from that show was so inspired that it was petitioned and accepted to be included into a NASA space capsule. Did you know that?

CK: [laughing] I didn’t know it.

SK: I didn’t know that but that’s great!

You didn’t realize that your visit to Marin County to petition the Dead not only saved the company but may still be having extraterrestrial intergalactic ramifications.

SK: That’s funny.

The Oregon Country Fair is the granddaddy of summer festivals, now celebrating 50 years. I went only once but loved it. You’ve been at the root of this tradition. Can you explain the connection and what makes the magic there?

SK: It is a fun interesting gathering, an escape from reality that started small. It’s hard to believe it’s been 50 years but when I look at how old our kids are—yep—it’s been 50 years! You used to know everybody. We’ve been a food booth for all these years so it’s kind of a working weekend. For sure it’s simpler to just come and attend and wander around than it is to operate a food booth but everybody comes by to say hello. There’s great people, great music, great art, great crafts.

What I appreciate about the Fair is its vigilant steering committee and artisanal ethos. It’s not like you’ll find Coca Cola and Pepsi products sold there, or any packaged goods. It’s unique and very strict and everything is handmade. This creates a unique high vibration in the woods.

SK: That’s true. I was on the food committee for 25 years and that’s what we did. We followed that criteria on the food side. On the craft side it’s the same thing. You have to be the one making your stuff. You can’t bring in pre-made stuff. There’s been some great food that started at the Fair, people making their little dream thing that evolved into products that are part of the natural food movement. It’s been an incubator.

Coconut Bliss is another home-grown artisanal brand.

SK: Yep. I remember when Luna and Larry came for the first time to the food committee with their application. They were selling some Coconut Bliss product in a few stores here in town but and we accepted them first as a food cart. Then people found them and it went from there. Rising Moon Ravioli is another one that started with a booth. I’ve enjoyed having my hand in knowing these food people and seeing them come along.

The Grateful Dead again played a hand in cementing the tradition of the Fair ten years later in 1982.

SK: The 1972 concert became such a marker that there was a push to do it again in ’82, which we did. The Fair had been renting the land and this concert, which was another great concert, gave the Fair the rest of the money needed to finalize the land purchase.

CK: We probably did the first frozen yogurt ever made then but we didn’t call it frozen yogurt. We had not a clue of what to call it. Eventually we made ice cream bars and Ken Babbs didn’t know what to call them so he eventually called them Yogi Bars.

Your family maintains close ties in the music business.

SK: Our son Kit went on to produce several other Grateful Dead shows. Along with being the operations director at the Creamery he runs the McDonald Theater and Cuthbert Amphitheatre in Eugene and keeps the family with our fingers in the music industry and the concert business.

And then there’s the Huey Lewis Bay Area connection. Can you tell the story?

In the early mid ’70s one of our first yogurt distributors in San Francisco was a gentleman named Gilbert Rosborne. Gilbert was a magazine distributor and was originally from Eugene. He was going to all these stores in the Bay Area and he says, “I could distribute yogurt. Let’s figure that one out.” So he put together this little company and got himself a cold storage place down in San Francisco. He would come pick up yogurt and take it down there and distribute to the stores. His partner was a kid named Huey Lewis who was a musician playing clubs at night and delivering yogurt in the day.

Eventually Huey became quite a star. He always says that he wrote “Working for a Living” while he was driving yogurt down to stores in Santa Cruz. He’s a neat guy and we’ve been privileged to know him all this time. Finally his music started paying off to where he didn’t have to be a yogurt distributor anymore.

He’s older than I but we went to the same high school.

SK: Is that right? Kit had him at the Cuthbert Amphitheater a few summers ago. It was fun. So it continues on. Keep those connections.

In 1994 didn’t you experience a fire that just about wiped you out?

CK: It started upstairs in the storage area, probably a fan short that ignited the wood or something. But it pretty well flattened the Creamery, which is a complicated monster full of many moving parts. I had counted that we had 350 motors, and now we’ve got double that again. But once the Creamery burned down—whoops—you’ve lost your market. And whoops—you’re out of business. But we put it all back together and were producing yogurt within 28 days.

SK: Just in time for the June 1994 Grateful Dead concerts at Autzen [University of Oregon]. We were rebuilding around ourselves as we were manufacturing. It was a colossal effort working around the clock. Actually about ten days after the fire this thing happened when we were like empty shells. George Siemon, who was starting Organic Valley, was making a visit to Oregon to talk to farmers who were transitioning to organic. I don’t believe I’d met him before and I said, “I’d love to meet you. Our creamery’s not quite in a production state right now but come on by, we’ll talk.”

So he got here on a Saturday afternoon and looked at the building. I was kind of, “Oh yeah, we’re building this, we’re gonna do this. We’ll be back up running in a couple weeks.” I think he thought I was completely mad because the whole thing looked like it would never run again. Anyway, he came over to our house and we had dinner and this wonderful conversation. He actually ended up staying all night at the house because we talked so long. He was operating a cooperative, and this is what Chuck’s dad operated, a dairy cooperative. We were going to be part of this organic milk pool that was being created. George was proposing knitting these amazing networks together. We have been working partners with Organic Valley ever since and they are great friends. It’s been a good ride.

CK: He’s pushed Organic Valley into a very successful business.

You’re old-time survivors in the natural products industry. Are you surprised at the growth that occurred?

CK: I’m only surprised at how slow it is occurring. I think it takes really a long time for something to happen. Take probiotics. As I sit here I know that I may live longer if I eat probiotic yogurt—but not many other people know that.

I remember these funny old [Dannon] TV commercials that showed old Russians who lived to be over 100 and what they had in common was that they all ate lots of yogurt. Do you know what I’m talking about?

CK: I do. But the thing you’re talking about is facts that are 80 years old. These are not new facts. Yet it’s taken 80 years for human beings to attempt to come around. They’ve done the same study in Korea where the people that eat fermented food live longer. And it’s not the cowbell, it’s the bacteria. This world of probiotics is way bigger than you can imagine and can influence your everyday health unbelievably.

What is your sentiment about this new era of synthetically engineered foods, gene splicing, and new genetic modifications that technologically can generate cell-based foods—meats—non-organically in fermentation labs and not on farms?

CK: It’s hard to even step into there. SK: It’s not that we don’t believe in it, it’s just that it’s not what we’re doing so I don’t really have an opinion.

What trends in the natural products industry do you find positive, and which not so much?

SK: The natural products industry is like anything else that starts grassroots. At the first Natural Products Expos there were maybe 50 or 60 manufacturers with booths and everybody was in one room. That was all the new natural products that were available. Now it fills the entire Anaheim Convention Center plus the hotels. A tremendous amount of the products shown are owned by large corporations, so the natural-organic movement has obviously caught the attention of large food companies because it was a positive thing. And they wanted it in their world too.

CK: That’s true of the yogurt world. We have a hard time competing with gigantic companies that are so big that they own the store. For us to exist in that world is really difficult.

SK: It’s challenging for a small family-owned company to continue to thrive. But when you make good products and you have a niche that people respect hat’s where it all is. The merging of so many brands under larger corporate shields helps get good food out to more people, which was always our goal. Generally there are more and more people eating better and better food in spite of it all. Even if they’re owned by big companies it doesn’t necessarily mean that’s a negative. That is just the change in the industry.

Surely you’ve been approached many times but you put an emphasis on running an independent family business.

SK: We haven’t exactly been approached. We just get a lot of feelers, a lot of letters, you know, saying there are people interested. That is not something we’re pursuing at this time at all.

CK: Too busy to think about it. We have a hard time seeing the forest for the trees—the classic small business problems. When the Creamery was young it was run almost all with cousins. The effect was we put ‘em all through college.

Don’t you have the longest track record of employee longevity, with folks sticking around for decades?

SK: That’s true. The folks that started with us at the beginning have all now retired. I mean we have I think fifteen plus people who have actually retired and who had been with us anywhere from 30 to 45 years when they retired. It speaks well of the kind of family company that we attempt to operate. Now the challenge is finding really good employees to join. People are searching for good people. Replacing long-term employees is a challenge because you’re losing that intellectual historical depth. The people that started with you when you were struggling at the beginning and stayed with you through when things were successful, they have a different feel and respect for their job that a lot of times the newer folks don’t have. They don’t know what it was like. They’re doing a wonderful job but they are reaping the rewards of the folks who struggled from the beginning.

There’s this funny saying, “Hippie marriages don’t last,” but you’ve been together more than 60 years. Your brother Ken was married from 1956 until his death in 2001. Hippies I know like Wavy Gravy and Larry Brilliant too have been married for more than 50 years.

SK: We enjoy each other. We have these wonderful children. We are running this business. It just seemed like the right thing to do all this time. I don’t really question it very much. I can’t imagine it being any other way.

Like any family you’ve had your tragedies. I hate to bring it up but Ken died too soon and so did his son, your nephew, Jed…can you tell the story?

CK: Ken died too soon, but it wasn’t as big a shock as Jed dying. Jed was a wrestler and he was tough. He wrestled for the University of Oregon and [in 1984] they took a van to Pendleton and were going across the top of the mountain when it slid off the road, turned over, and fell down a 300-foot mountain. That was pretty sad. Ken never got over it. It’s the kind of thing you don’t get over.

SK: Thankfully we were honored to have Chuck’s mother, Geneva, with us up until a year ago when she passed away at age 101. She was a great lady with a delightful wit and wisdom. She was really the connection, the family matriarch.

CK: We fed her a lot of yogurt and a lot of kefir. And the other side of it is we’re full of babies right now. We now have a great-grandson who was born four weeks ago. So another generation is coming.

Are you optimistic about the world your great-grandchildren are inheriting?

SK: Well, some days I think about that and I’m not too optimistic. I think, “My goodness.”

What advice might you have for young people reading this who might be inspired by the kind of career you found in the natural products industry?

SK: If you can work for yourself and be creative, creating something that you are in charge of, whether it’s in natural products or whatever… Chuck and I always said after a number of years of running our own business that we would be terrible employees. We were so used to being so independent and running things the way we saw fit. So my advice is try to be independent and work for yourself or with a group of friends to do something that’s viable and important and earns you a living that allows you to enjoy life and family.

CK: I recommend independence. Take a chance on something you believe in.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor-in-chief of Common Ground.