Portrait of the Activist

as a Young Man

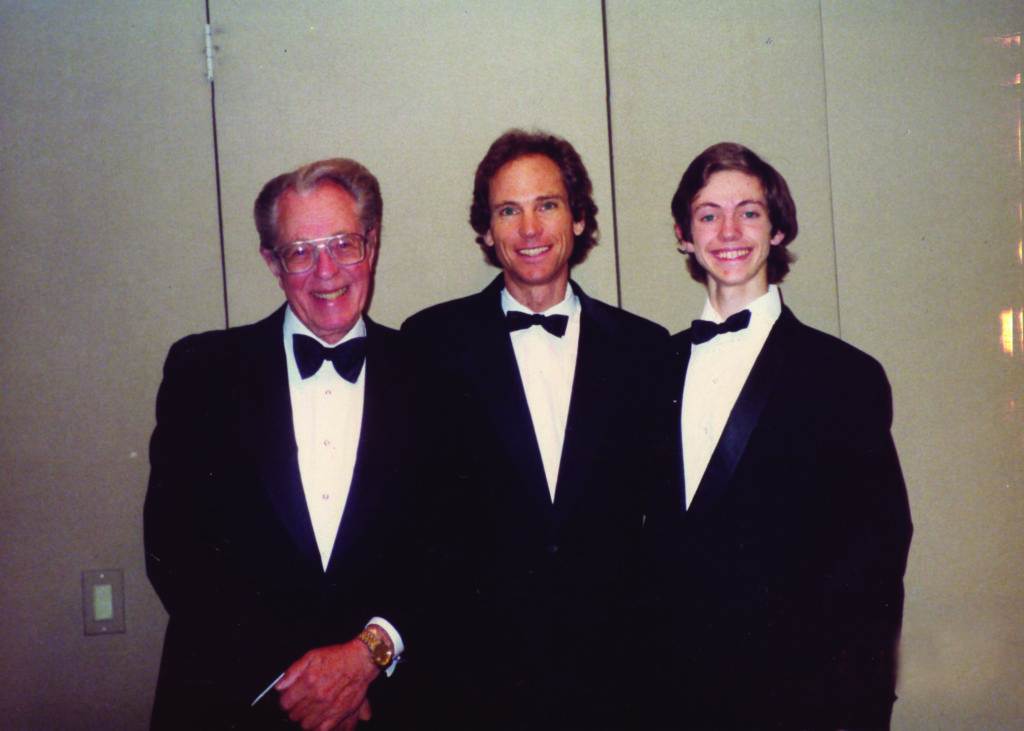

Ocean Robbins is the son of food health pioneer John Robbins (Diet for a New America) and the grandson of Irving Robbins, the cofounder of Baskin-Robbins. Ocean was born in a remote log cabin in 1973 after his father walked away from his inheritance and the opportunity to run the ice cream empire. Living a back-to-earth lifestyle, Ocean became expert in food and environmental health and at 16 cofounded Youth for Environmental Sanity (YES!) and proceeded to tour the US and the world for 20 years fomenting youth activism. He is cofounder of the popular Food Revolution Network, a global community of over 350,000 members standing up for healthy, sustainable, humane, and delicious food. The network’s online summits are free, attracting over 400,000 participants and world-class speakers such as Paul McCartney.

Ocean is adjunct professor at Chapman University, the author of multiple books, and the recipient of the prestigious Jefferson Award for Outstanding Public Service. His tireless activis m is sweetly blended with spiritual insights—some of which were gleaned by raising autistic twin sons. Our interview took place on the 19th anniversary of his wedding to his wife, Michele, whom he considers proof of God.

Common Ground: How would you describe yourself and summarize your work?

Ocean Robbins: My title is CEO and cofounder of the Food Revolution Network, which is an online-based education and advocacy community that is standing up for healthy, sustainable, humane, and delicious food for everyone. Taking a step back I am a concerned citizen of planet Earth who is outraged by the level of needless violence, suffering, misery, and death that is taking place and am committed to using my life to ease the suffering and to bring more joy, beauty, sustainability, and resiliency to humanity’s experience on this planet.

Your grandfather famously cofounded Baskin-Robbins. Can you tell the story of the company’s origins?

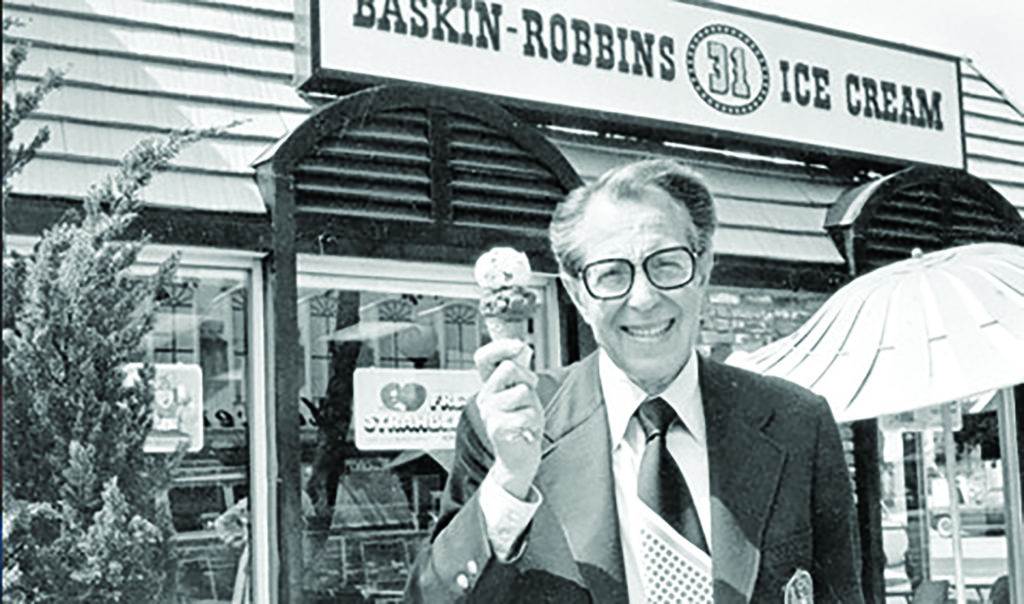

Back in the forties most people were content with three flavors of ice cream strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate. My grandpa Irv Robbins, a consummate entrepreneur, saw an opportunity to expand the palate and came up with the idea of a new flavor for every day of the month—hence the 31 flavors concept. With his brother-in-law Burt Baskin, they brought a lot of joy to a lot of people. People thought ice cream was a way to have fun, and it became a highlight or sacred ritual for many families. Nobody knew that ice cream was linked to heart disease and cancer and health ailments. To this day there are more than 7,000 Baskin-Robbins stores in 50 countries.

Your father is a famous health crusader who famously turned his back on his potential dynasty.

He grew up with an ice cream cone–shaped swimming pool in the backyard and 31 flavors of ice cream in the freezer. As a youngster he was inventing flavors such as Jamoca Almond Fudge. He was groomed to run the family company, but when he was 19 years old he said no. He refused a path that was practically paved with gold to follow his own “rocky road,” as we joke in the family. At that time his uncle Burt was dying of heart disease and ended up passing away at the age of 54. Burt was a very big man who had enjoyed abundantly of the family product. He had tremendous wealth and a family he loved, but not his health and ended up leaving a widow and fatherless kids. My dad simply didn’t want to spend my life selling a product that might contribute to more broken families, so he walked away from all that and all access to the family’s wealth. He and my mom built a one-room log cabin on a little island off the coast of British Columbia and grew most of their own food and lived on less than $500 a year. I was born in that cabin. My parents practiced yoga and meditation for several hours a day and named their kid Ocean.

Unlike me, it sounds like you didn’t eat much Baskin-Robbins.

[Laughs] No I didn’t, nor much sugar of any kind. Blackstrap molasses was the only sweetener in our house, and we went through only a bottle a year. It was a treat to be allowed to have a teaspoon of it on my oatmeal. I grew up monetarily poor but feeling rich because I had time with my mom and dad and beautiful nature. Some would say I was deprived for not having ice cream and Twinkies and Kentucky Fried Chicken, but I had something more valuable than any of those things, which was the foundation that set me on the right foot toward a healthy life. You know the saying: “One who has health has many dreams, but the one without health has but one dream.

Without health nothing else seems to matter. Ask anyone who has ever been in intense pain—when some part of their body isn’t working. They would do anything to make that part work again. I don’t care how hard you meditate—when any part of the body shuts down you’re probably cursing God. My parent’s choice to raise me eating healthy food is probably worth more than any hug or gift or material-financial support they ever gave because it helped me have the foundation for a thriving life.

How was religion or faith expressed in your family?

All of my grandparents on both sides were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who fled persecution in the early part of the 20th century. Both my parents grew up in Southern California in households that were Jewish but didn’t have a lot of joy or spark to their Judaism. My parents came of age and fell in love in the 1960s and were called to find their own path. They didn’t follow a specific religion but chanted and meditated and had a deep sense of faith and attunement to their consciousness, to wisdom, to a higher power—or to what they might’ve termed a universal intelligence. Some would call it the Holy Spirit, some would call it the forces of life, or the Creator, or God. I grew up in a theist context, which is to say loving God more than any specific religion, while at the same time knowing that I was ethnically Jewish.

With names like Baskin and Robbins one might assume a WASPy Episcopalian background.

If you go back one more generation, the names were actually Baskinovitch and Rabinowitz. I come from a family that gave up its very name in an effort to assimilate to a dominant American culture and then became a leader within that culture. Baskin-Robbins sold more ice cream than Boskinovitch and Rabinowitz would’ve sold, but I’m struck by the blessing and the curse of the status quo normalization. I think we all face choice points about whether we’re willing to be radically ourselves and at what point we want to assimilate to a status quo.

I’ve been blessed in my life to have traveled to see how different communities carry their own unique wisdom and genius and how that cultural diversity, rather like biodiversity, is critical to the function of a healthy socio-ecosystem. I’ve see a connection between the monocultures and monocrops—of both ecology and of the mind. A healthy biodiversity is being lost amid cultures and the names of peoples in the world. The number of spoken languages is going down drastically as indigenous cultures are being exterminated. We are living in a pandemic of the sixth extinction where Monsanto and a couple other companies now control half of the world’s seed supply. I think that biodiversity is part of our strength and part our resiliency.

So we’re just talking about names here—which on one level is a trivial kind of a thing, but I stand for a world in which more people feel respected and can have dignity in being who they are rather than feeling overwhelming pressure to conform to a status quo that may ultimately degrade their liberty and our survivability as a species.

And biodiversity of faith . . .

I’ve worked closely with people from different faith backgrounds and felt the common flame that burns at the center of many of the world’s major faith paths. There are common values too—like “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” There are morals and such a thing as right and wrong. There is such a thing as proper conduct and consequences for what we do. In all religious paths you find that people find strength in coming together. In the Jewish peoples’ history, looking out for each other was sometimes necessary for the survival of the people. I’ve been curious about Judaism throughout my life, and the time I spent in the Holy Lands played a profound part shaping my life.

Can you share about that?

Back when I was 16 I cofounded an organization called Youth for Environmental Sanity, or YES! We toured all around speaking at what we called YES! jams to youth about the environment and sustainable food choices. Our thought was that if we could reach high school students we could do the opposite of preaching to the choir. This Middle Eastern jam was in Jordan in 2008, and it gathered young leaders from 15 different countries who were working for peace, justice, sustainability, human rights. These included people from Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Palestine, Israel, Iran, and many other countries that were at war with each other. There were people at this jam who would be jailed back home for simply sitting with each other, so we had to keep it on the down low and couldn’t take pictures.

I was overwhelmed by the stories of people’s lives, and I felt the legacy of blood and sweat and tears and prayers that would saturate these ancient conflicted lands—the birthplaces where Islam and Christianity and Judaism share some of their most sacred places, all within a couple miles of each other. I witnessed the depths of culture and history and how deeply people long for freedom and how millions have struggled to survive in a hostile desert over centuries. I was overwhelmed by the enormity of the conflicts but also by the depth of love and courage of those who came to build bridges of connection and trust across these divides.

On the last day we went to a waterfall on the edge of the Dead Sea called Main Hot Springs, and it’s the lowest point on earth. The water is heated from deep in the earth and bubbles up and pours down at about 105 degrees. It was so intense tumbling on my head that I could barely stand up under it. And I found myself just weeping—sobbing actually. Then these words came out of my mouth that I kept repeating and never forgot. The words were “help me to release all ambition, all attachment, and all desire for all that is not so.” It’s become a mantra that I repeat every day. Under the waterfall I realized the extent that I was holding onto the myths of my own ambitions and ego desires and how all that was not real was creating suffering and misery. I let it go.

Powerful.

As humans we want to believe stories that make us feel good. If a lot of things don’t make us feel good, then we look away and hold a smaller field of vision. Like the politician who only looks at those polls that show he’s going to win.

I too don’t want to accept that child abuse and nuclear weapons are going on. Or that people are going hungry, that animals are being tortured in factory farms, that children are growing up with diabetes, and that many feel unsafe living in warzones. There are many things I find unacceptable, but they are so. When I actually embraced the reality, I become more powerful in my ability to respond. What I felt coming out of the hot springs was that when we are in opposition to what is so in the world, we lose our power and our truth. But I also learned that what is real is the capacity for change.

As an activist wanting to create a just and more spiritually fulfilling, beautiful, sustainable human presence on this planet, I could have the tendency to silo-ize my perceptions and demonize the other to look for facts that buttress my worldview. I prefer to have an open mind and a curiosity rather than a mind full of half-truths. When we are curious—when we know that we don’t know—we become present and available to learn and grow, and therein lies a great deal of power.

You are identified as a voice of a younger generation. Can you talk more about YES!, Youth for Environmental Sanity? I love the name.

Inspired in part by my dad’s leadership in working for healthy food choices, I cofounded YES! with my friend Ryan Elision. We were 16 years old and had this crazy idea to travel across the country in a beat-up VW Wagon to speak at school assemblies in a 45-minute presentation about the environment and about sustainable food choices. Staying in people’s homes from Hawaii to Harlem, we reached over 650,000 students, which is about 2% of the US high school population.

We spoke in rich schools, poor schools, suburbs, ghettos, rural America—we were a message of youth empowerment and youth leadership because we were teens sounding the alarm that our planet is in crisis and that our generation had the most to lose—and to gain—by saying “young people can change the world.”

We encouraged young people to eat lower on the food chain and write letters to representatives to advocate for recycling and for using recycled products, which was not widely done in the nineties. We were advocating for boycotting companies that were destructive in their environmental practices and for buycotting—supporting companies doing good things.

We learned that for some young people “the environment” meant saving green spaces or saving the rainforest but that for others “the environment” meant gangs and concrete and trying to get home from school without getting shot. We learned that three out of every five African Americans and Latinos lived in a community with a toxic waste site. We learned about inner city kids who’d never visited a park in their lives and were suffering from lead poisoning—who were bearing the brunt of environmental pollution. So as environmentalists we had to expand our definition of environmentalism to include people, and that’s when we expanded.

We realized that the struggle to end racism and social injustice and the struggle for environmental sustainability had to become one struggle. That’s how the YES! jams evolved from our speaking at schools about eco-sanity to larger weeklong gatherings aimed at bridging communities and ecosystems. We worked with leaders in over 65 countries and started organizing jams all over the planet like the one I described in Jordan. The impact was tremendous as we brought together leaders working for peace, human rights, social justice, sustainability and helped these leaders find common ground and sustained partnerships across power, race, class, religious, and national divides.

You traveled a lot?

I had the opportunity to travel all over the world in environments I never imagined. I saw that how people ate had a huge impact. For example, I worked in Senegal where there was a strong tradition of importing white rice from Vietnam as a remnant of French colonialism, since France had colonized both those countries. It’s insane, but white rice is a desired staple in Senegal; meanwhile, the traditional food is millet, which they could easily grow there. When the economic crisis hit in 2008 and fuel prices doubled and made imported rice unaffordable, the people were literally starving to death instead of growing millet. That would have been the time for the government to say, “No more rice, eat millet.” But instead the response was to take the limited tax revenue and fund subsidized imported rice while the local farmlands stayed fallow. White rice is associated with the good life, and millet is associated with peasants and poverty. The lunacy!

Working in India and China I saw the infiltration of McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken. As wealth arrived to these countries, I saw proud nations that historically had low rates of obesity shift to expanded waistlines as hospitals were filling with people getting diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and heart disease. The American way of growing and transporting and processing food has spread like a virus through the world’s food supply as companies like Monsanto, McDonald’s, and Baskin-Robbins dominate over local traditional cultures, and food systems are being wiped out.

Our big export—the American diet—is quite the culprit, huh?

Nearly 70% of our population is overweight or obese. The average American eats more than 66 pounds of added sugar per year, enough to overflow a dumpster over the course of a lifetime. We have the world’s highest rates of chronic illness in human history. In the largest study ever conducted on the causes of human mortality called the Global Burden of Disease, they concluded that in the United States alone, diet was causing 670,000 deaths annually. This is more than the number of Americans who died in World Wars I and II, the Korean War, Vietnam, and both the Iraq wars and the Afghanistan war combined. This is all in one year. This wasn’t from other countries’ bullets; this is from our own knives and forks.

Crazy.

It’s clear that our way of eating is killing us. By changing our diet, we could eliminate obesity by 100% and more than 90% of the cases of heart disease, 80% of the cases of diabetes, and the majority of cases of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Maybe 50% of the cases of cancer. The costs of these diseases on our wellbeing and on our economy are incalculable. We spend 19% of our gross domestic product on disease treatment. The fact that we can do something about it is a source of tremendous hope.

Are you proposing a vegetarian diet?

The data is clear that we need to eat less animal products and more whole plant foods. Personally I identify as plant-powered or plant-strong. I eat some wild fish and some pastured eggs, but I base my diet around whole natural plant foods. That’s consistent with my take on medical literature and my own ethical sensibilities at this stage in my life. I have profound respect for people who for ethical or ecological reasons choose to be 100% vegan. I also respect those who don’t. There’s no perfect one-size-fits-all diet. We need to listen to our own bodies, but the medical literature is consistent and clear that eating whole foods with lots of fruits and vegetables—and for most people legumes and whole grains—is optimal for human health.

Can you explain how a meat-based diet impacts climate change so tremendously?

While the effects of a meat diet are arguable regarding health, what’s not arguable is that animal products have a high environmental impact. There are two main ways that cattle gain weight. One is by grazing and eating grass, which in theory could be sustainable if it was sustainably managed, but in practice it rarely is. For example, rainforest beef, which is technically pasture-raised, creates widespread desertification and is a central driving cause behind the destruction of the tropical rainforest. In the US basically half our land is being used for livestock and in many cases is degrading the ecosystem and its biodiversity. It’s never a good thing for our planet when forests are cut down to create grazing land.

The second way cattle are raised is by what some call factory farming, where livestock are eating grain and soy in concentrated feedlots. In many cases cattle start on the pasture and then gain more than half their weight in these feedlots, where they are placed in very close quarters and pumped full of antibiotics and hormones. They are fed a totally unnatural diet (that may even include making them into carnivores), consuming large amounts of grain and soybeans. In this environment the feed-conversion ratio is such hat it takes about seven to nine pounds of grain and/or soybeans to make one pound of feedlot beef. The inefficiency is so profound that if in the United States, we were to reduce our beef consumption by 20% we’d free up enough grain and soy to feed all the people who are dying of hunger on the planet this year.

The reality of eating up the food chain is that it takes a lot of biomass to create one pound of flesh because all that grain and soy and grass needs to be grown, right? If we’re converting forests into grasslands, there’s a devastating carbon impact. When we take large amounts of agricultural land to grow GMO corn and GMO soy—since most of our GMO crops are being fed to livestock and not to people—we’re pouring chemical fertilizers from fossil fuel–based sources with huge environmental impacts.

It’s hard to wrap my head around the fact that cow farts are more damaging than exhaust pipes when it comes to climate change.

Yes. [Laughs] Cows have four stomachs and produce a lot of flatulence, or methane excretions or [laughs] we can say cow farts. This is actually a major driver of climate change. To be clear, we’re not talking about air pollution. The pollutants coming out of the tailpipes are vastly more impactful on asthma rates than cattle farts, but when we’re talking about the greenhouse effect, methane is 20 times more potent a greenhouse gas than CO2. When CO2 is combined with methane, they surround our planet like a blanket, causing it to get too hot. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization did a study of the causes of climate change and concluded that meat—most specifically, beef—is responsible for more climate change than all transportation factors combined. That’s more than all the cars, trucks, airplanes, ships in the world put together. This in turn has led to statements such as “You’re better off—from a climate impact perspective—being a vegan and driving a Hummer than being a meat eater and driving a Prius.”

Personally, I don’t think it’s all or nothing, but if you take in these facts and care about a sustainable climate then we clearly need to eat less meat. If you want to walk lightly on the earth the best way to do that is to eat a plant-strong diet, and it so happens that choice will also contribute to your chances of a having a long and healthy life. It’s a wonderful choice personally and collectively.

Let’s talk about water in this equation.

We’ve been talking about the environment and beef production, but we should also add pork and chickens and talk about the profound impact this is all having on our water supplies. The grain-to-meat conversion for beef is the most inefficient at between seven to nine pounds, while it’s about four or five for pigs. For chickens it takes about three or four pounds of grain to raise one pound. The point is that all this grain and soy need to be watered, right? To give a number, it takes more than 2.5 thousand gallons of water to produce one pound of feedlot beef in California. That’s enough to stack gallon water jugs a mile high. It means that you could save more water by not eating one pound of meat in California than you could by not showering or six months.

We’re in a longstanding drought where we talk about taking shorter showers and “If it’s yellow let it mellow” and turning off the water when we brush our teeth and selling low-flow toilets, and these are all wonderful steps—and we need to take all of them. But in California, with all our golf courses and all our swimming pools and all our showers, we still use more water for livestock production than for all civilian, municipal, and business uses combined. If we’re going to have pasture-raised meat, it’ going to come from animals that grazed on irrigated pastures because we don’t have green grass in the summer. It turns brown, especially in a drought—and cows don’t eat brown grass. That irrigation requires an immense amount of water. Here’s a reality: in California we are exporting 100 million gallons of water a year to China in the form of alfalfa. Even in a drought we are subsidizing Chinese factory farms by sending our precious water.

Wow

California’s got a water crisis, but it’s not just here. Humanity is in water consumption overshoot. We are drawing down our aquifers all over the planet. If our aquifers and our wells run dry, we’re going to lose the ability to feed our populations, and we’re going to lose the ability to have drinking water from the tap. Probably within the next generation, especially as climate change unfolds and certain areas become desertified, we may see billions of environmental refugees who can no longer live in whole nations. By some estimates half the water in the United States goes toward livestock production, but this is perhaps a luxury that future generations will suffer.

What feedback do you get from young people about the whole Trump phenomenon of climate denial?

The Republican Party is the only major political party on the planet that denies climate change as something that is real and is being caused by humans. An overwhelming body, 98% of scientists, agree about climate change, but only one political party remains an outlier. For a lot of young people there is a growing dissatisfaction with the status quo, and people wonder why a 72-year-old Bernie Sanders became so popular with young people. Whether rightly or wrongly he—and Donald Trump—were perceived as being willing to say “FU” to the status quo establishment and make radical systems change to a system that is perceived as corrupt to the core. For example, in the world of food policy alone, it is Monsanto and the biotechnology industry and McDonald’s and Coca-Cola and the junk food industry that have masses of lobbyists—so guess where the government subsidies go? No wonder it costs so much to eat healthy organic food. Because upwards of 98% of our subsidies go to commodity crops and less than 2% go to fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds. We’re subsidizing high-fructose corn syrup and factory farmed animal products and processed junk.

I believe that left and right politics have values that are profound and beautiful in human life, and I deeply respect political discourse. At the end of the day Hillary became associated with the status quo and didn’t light it up for people, while Trump promised to drain the swamp. A lot of people said, “That sounds beautiful. We want to drain the swamp,” but ironically and tragically he’s filling the swamp—with swamp creatures. He puts polluters in charge of the EPA and chemical companies and factory farm owners in charge of our agricultural policy and fast food heads in charge of labor. He puts Goldman Sachs in charge of our economy. The so-called champion of the people is not.

Speaking of young people, you have a couple of your own—special needs kids if I’m not mistaken. What has parenthood taught you?

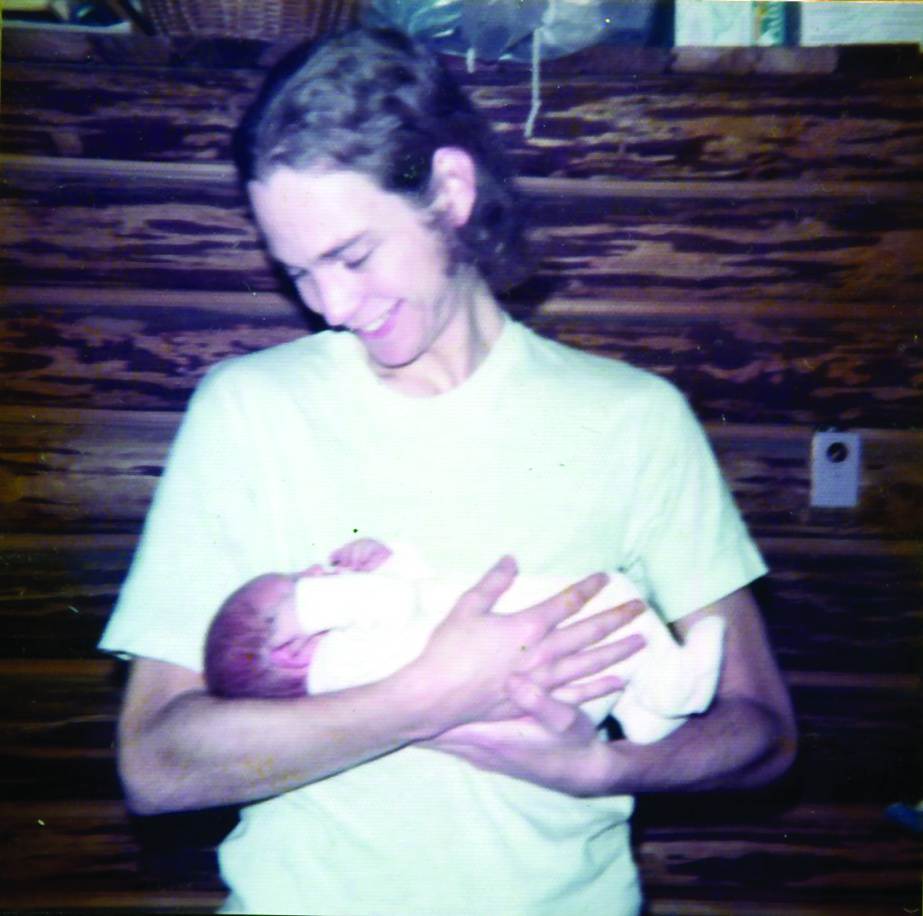

I’m a father of identical twins boys, River and Bodhi, who were born nine weeks prematurely, are awesomely autistic and are now 16 years old. They are unique, special, brilliant, creative guys who struggled with special needs and didn’t walk until they were two and didn’t talk until they were five and are now going through their unique teenage-hood. They have to work twice as hard as many people for results.

Being their father has made me a deeper, more loving human being. Because growing up as an only child I felt loved and special, and I was bright and gifted, and academics came easily to me, and I had something of a superiority complex. But my kids don’t have as much confidence sometimes because they are aware that some things are hard for them socially and academically. Yet I love them so much just as they are. Growing up, my dad said to me many times that he was proud of my accomplishments but that he’d love me just as much if I were autistic.

Interesting. Kind of prescient, wouldn’t you say?

I know, right? And here I am and I get to find out. Is my love for them conditional on performance or behavior? Or is it truly just because? I’m finding that I love them with all my heart and not because they’re on the fast track to Harvard but because they are precious, beautiful beings who bring all the love in their hearts to the world. And they deserve total love like everyone.

This prompts me to look at my own self-love and self-respect based on conditions of “Am I worthy? What about my performance?” Can I love myself just because? It goes back to the waterfall experience in Jordan. “Can I love the world and humanity with all its flaws—just because?” This whole planet deserves love. When we come to that foundation, we get off the high horse of self-righteousness and stand in a truer, more humble place—toward a deepened sense of collective humanity.

Do you ever put God in that equation?

I do privately. I think of God as a miraculous wisdom or great spirit force that guides my life. It’s far too wondrous to be collective chance. As we’re conducting this interview it was 19 years ago today that my wife and I celebrated our marriage—the woman of my dreams. It felt like God had stepped in. How else could somebody so perfect have emerged?

Aw-w-w. Fantastic. But when your twins were born with challenges, did you wave your fist at God?

Of feeling like why me? Sure. When my kids were born I was just furious. “What did they ever do to have to be hanging on for survival at birth?” They couldn’t breathe, they couldn’t swallow on their own. They had to have tubes forced down their throats every three hours to feed. They were surrounded by beeping machines and bright lights and invasive tests when they weren’t even ready to open their eyes. That was when my perspective on God shifted because I felt that if God is a force that let this happen then maybe this serves a greater purpose. Maybe this is to become more wise and loving—on behalf of this planet.

There’s no way you could look at every child born to a starving mother and say, “This is karma. This is fair.” It’s not. It’s deeply unfair. It’s brutal. A part of me says it’s wrong. Yet it’s so. Mortality and suffering is part of the human condition. That is where my spiritual faith kicks in when we ask, “What then?” Do we stop fighting and try to pretend it isn’t so? Is that any reason not to love? Is that any reason not to create as much health and vitality as possible?

When my kids were born and struggling, I was struck that we had a medical system that was protecting them and making their lives possible. Had they been born in certain places in Africa, they would not have lived. Ironically, I felt grateful. There’s a responsibility that comes for me with my kids being alive—which is that I want to help more kids make it. With all the healthy eating in the world, we couldn’t prevent the fact that our kids were born prematurely. There’s still going to be suffering and death. But it could be less—maybe be a lot less. In my work and my life, I want to keep standing for less pain and more joy.

by an Individual 35 or Younger

Do you ever lament that you or your father didn’t choose a more comfortable lifestyle?

When I was 12, having grown up in this little cabin in the woods without money and my mom making her own clothes, I remember the culture shock of visiting my grandparents in Rancho Mirage and seeing their Rolls Royces and conspicuous consumption with fancy country clubs and a staff of a dozen servants and groundskeepers. They were very loving toward me, but I felt a loneliness in their hearts. They seemed afraid everyone was after their money and only hung out with wealthy people and hired help.

One day they took me out for a big shopping spree and bought me a huge amount of clothes and books and toys and school supplies. Then my grandfather sat me down to say, “We’ve been thinking that not all children go in the same road as their parents. Your father certainly didn’t. But you might decide that you want to take a different path. We want you to know that if ever you decide you’d like a different kind of life—you’re always welcome with us.” I know he came from a place of love, but it sounded just like Darth Vader saying to Luke Skywalker, “Come to the dark side.” I was a big Star Wars fan. So I was very polite and thanked them for caring, but that ended the conversation. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

Did your father and grandfather ever reconcile?

My grandpa was a stubborn cookie who was invested in the status quo and was pretty mad at my dad for walking away from his life’s work, but later he changed, proving anyone can change, and he took advice from Diet for a New America and started eating a lot more vegetables and improved his own health. He said to my father, “Johnny, when you left Baskin-Robbins I thought you were crazy, but you followed your own star, and I’m so glad you did and I’m proud of you.”

My grandpa was a stubborn cookie who was invested in the status quo and was pretty mad at my dad for walking away from his life’s work, but later he changed, proving anyone can change, and he took advice from Diet for a New America and started eating a lot more vegetables and improved his own health. He said to my father, “Johnny, when you left Baskin-Robbins I thought you were crazy, but you followed your own star, and I’m so glad you did and I’m proud of you.”

I feel that he blesses and supports what we’re doing and really loves it. In some interesting way I learned from him to think big—that you can scale up good idea and take it really far. He was a delightful manager—his employees loved him. Now that I’m directing the Food Revolution Network and working with a team and being a manager, I like to think I inherited a bit of his skill in helping a team to excel toward a shared mission.

You’re an interesting dude who has taught me a lot in this conversation. Thank you. And for all you do. Any final message to our readers?

Things become real and meaningful when they’re put into action. My hope is that if this interview has stimulated anything for readers I’d say, “Apply that in some way that makes sense in your life.” It might be to eat more organic, or local, or plant-strong, or sustainable, or fair trade. Maybe it’s telling someone you love them. My hope is that readers can take this opportunity to create more congruence between what they want and what they do.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.