Meet the Man Behind the

Mainstreamization of

Psychedelic Sciences

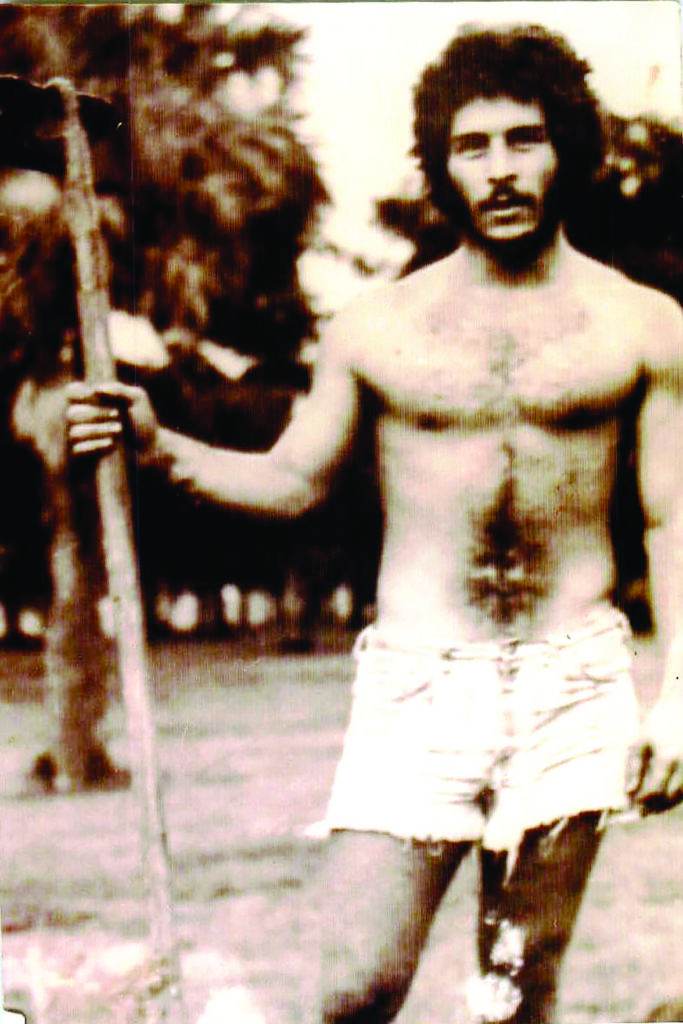

Rick Doblin was born in the Chicago suburbs in 1953 and has remained loyal to his Jewish heritage. His first interest in psychedelics was prompted in high school upon reading Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. When he found out that part of that beautifully written book had been achieved under the influence of LSD, he came to question the anti-LSD propaganda. As a freshman at the New School in Florida, he experimented extensively with LSD and mescaline with mixed results. The influence of Dr. Stanislav Grof proved to be a key turning point in 1972, whereupon Rick decided his calling was to become a psychedelic psychotherapist—something he’s yet to achieve. The reason why is part of an interesting story—the quick answer being that the politics got in the way, so he had to get into the politics.

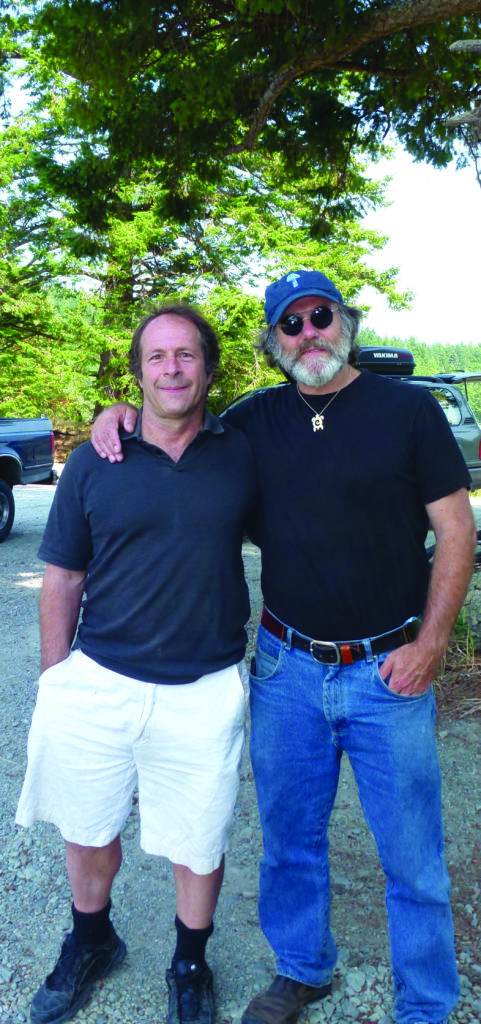

If you’ve ever wondered who is behind the surge of mainstream positive news stories about the acceptance of psychedelics, you can look to Rick Doblin, who in 1986 founded the Multidisciplinary Association for the Psychedelic Sciences (MAPS), now headquartered in Santa Cruz. Our interview was captured in San Francisco following the Psychedelic Sciences Conference and focuses on Rick’s life work—an uphill battle to convince Pentagon leaders that MDMA is perhaps the most effective drug for curing PTSD. MDMA cleared a major hurdle recently, having been approved for Phase III trials. Ironically, over the last 50 years since the Summer of Love, psychedelics have been symbolic of the anti-war movement.

You’ve become an overnight sensation—but only 30 years in the making! I say that because recently, there has been a slew of mainstream coverage about the newfound acceptance of psychedelics. The un-closeting of this taboo is the culmination of your life’s work to date. What’s going on?

[Laughs] Yes, a wide array of media outlets besides the New York Times and Rolling Stone have been covering this, including Stars and Stripes, Military, Reason magazine, RedState.com, the Navy Seals website. Fox News did a six-minute story. It’s not just in our bubble. We’re trying to build broad-based bipartisan support for MDMA research. Some groups are focused on veterans, while others are focused on childhood sexual abuse, adult rape, and assault—PTSD from its many causes. What’s making these articles so powerful in the last six months is that we’ve reached a critical threshold with scientific credibility.

What a long, strange trip it’s been! Fifty years ago during the Summer of Love, psychedelics were seen as synonymous with the anti-war movement.

It’s not like us hippies from the sixties and crazy nonprofits are developing this; it’s fundamentally transformative science developing into Phase III studies with mainstream credible figures and institutions saying this should be done. Rob Malenka, one of the top neuroscientists at Stanford, put out a call to arms saying all the tools of neuroscience should be focused on MDMA. Last summer he and his coauthor, Boris Heifets, published in Cell, which is one of the top-ranked medical journals in the world, arguing for the importance of this research because the world is in dire need of understanding more about empathy and compassion.

How did you get into the Pentagon?

We started by trying to work with the chief of psychiatry at the San Diego Naval Medical Center, as they had a 10-week inpatient treatment program for Navy Seals and Marines with PTSD. He wanted to do a study evaluating MDMA in that context but said he wasn’t high enough in the hierarchy. He said we had to get the admiral in charge of the facility to support it. The admiral said yes but that he wasn’t high enough in the hierarchy and said we needed to get approval from the secretary of the navy. All this just to do the small MDMA study!

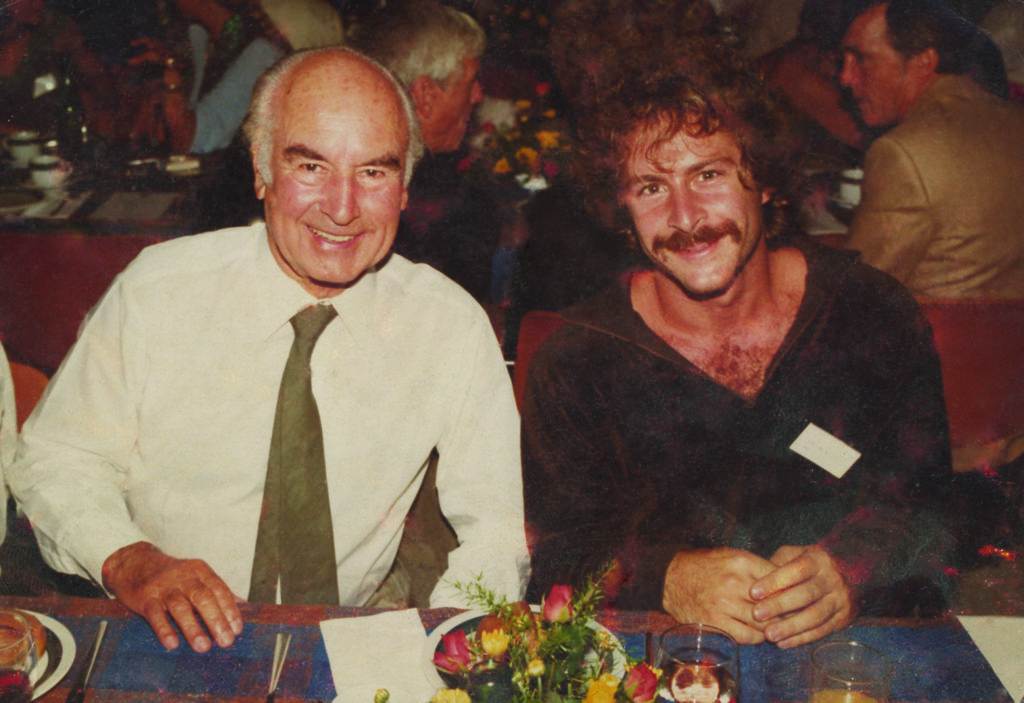

By this time I was collaborating with Dr. Richard Rockefeller, who was working with Doctors Without Borders as chair of their board of advisors and had taken an interest in MDMA for PTSD. He asked me, “What’s your hardest challenge?” I said, “It’s with the military.” It turns out Richard knew the secretary of the navy, and he spoke with him and the assistant secretary of the navy, who were sympathetic. Richard’s cousin was Senator Jay Rockefeller on the senate’s Veteran Affairs Committee, so we got a meeting in the Pentagon.

At the meeting there was another coincidence, which was that the assistant secretary of the navy had been a friend and classmate from the time I was doing my master’s at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard back in 1988–90. We had chosen different career paths, but he remembered me talking about MDMA back then. The navy surgeon general was also at that meeting.

Are you saying it helps to have Harvard credentials and friends in high places with names like Rockefeller? [Laughs]

[Laughs] It totally helped. In fact, it was essential. But that’s exactly why I went to the Kennedy School—to get the credibility I needed to work within the system. The first time I was at the Pentagon, I couldn’t help thinking about how yippies in the 1960s held an anti-Vietnam War protest by ringing themselves around the Pentagon—they were going to try to levitate the Pentagon. That strategy didn’t work, but all these years later here we were inside the Pentagon trying to talk to them about psychedelics, and it was working—sort of.

They too said they weren’t high enough in the hierarchy to move ahead. We had to go to the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, who had a $50 billion budget and a team of advisors to provide healthcare to all the military. At the same time, Sen. Rockefeller met the then head of the VA, Eric Shinseki, and later Robert McDonald, to encourage them to give the go-ahead to move forward with this research.

However, we had to fund the research ourselves. MDMA being a Schedule I drug was too politically hot. Also, our subjects couldn’t be active duty soldiers but veterans. As it turned out, the people we were to work with who had joint appointments at the VA and academic affiliations used their academic affiliations, not their VA affiliations. And the veterans in our studies were self-referred from outside the VA system. We could be in dialog with the VA’s National Center for PTSD, and they would be the one to suggest the researchers we worked with. We had to jump all these hoops, but this was how we finally got our toehold.

Reminds me of the quote “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Those Stanford Cell conclusions—I could’ve written those 30 years ago when I was first thinking about the need to integrate psychedelics into our culture. To have it now coming from mainstream voices is both incredibly shocking and satisfying. The DEA tried to criminalize MDMA in 1984, and we blocked them with a lawsuit that we won. Then they did an emergency scheduling in 1985, so we started MAPS in 1986.

You’ve been in the trenches observing PTSD victims. Can you describe what you’ve seen?

There’s this illustration I have—I can share it with you—of a soldier wading, holding a gun over his head. But instead of wading through water he’s wading through a river of pills. It’s a striking image. We’ve seen an enormous variety of everything thrown against the problem of PTSD—antipsychotics, antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs—and virtually nothing working. The only two FDA-approved drugs are SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) Zoloft and Paxil, and they don’t work well. They can control symptoms in some people, but they don’t address core issues.

In our very first study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, we examined people who had experienced long-term PTSD, with the average being over 17 years. In our study 83% of the people recovered after a few experiences with MDMA and could no longer be diagnosed with PTSD even though they’d had the same patterns for many decades. Some Vietnam vets outside our study were able to work through traumas they had been holding on to for 40–50 years within a relatively short period of time.

How does it work? What’s the miracle about it?

The lives of PTSD sufferers are dominated by the constant reminder that an old trauma is either happening or about to happen. They’re constantly jumpy and hypervigilant. Something about the MDMA reduces activity in the left amygdala where fear is processed, and there is enhanced activity in some of the frontal cortex where things are put in association. With an enhanced sense of presence and the suppressed fear of difficult emotions, a PTSD sufferer can have a sense of safety and a sense of belonging and connection while thinking about the most traumatic things that have happened. There’s something about this peaceful state that enables people to look at this trauma from the past without so much fear. Here’s the important part—they can safely place it in the past. They come to recognize that it’s not happening right now.

From fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) studies on patients before and after treatment, we can see that new neural pathways get created, and certain reactive, fear-based brain centers don’t light up as much. Some might call it miraculous, but when combined in this therapeutic approach it can quickly alter decades-old patterns.

You could say MDMA is the least psychedelic of the psychedelics in that it doesn’t interfere with your perceptions in the same ways that others do. MDMA doesn’t block a logical train of thought and is not ego dissolving. In a way it’s ego strengthening and strengthens self-love and self-acceptance. Given these properties, we can deliver it to people in a therapeutically comprehensive way that focuses on preparation and support during the experience and follow-up integration so that PTSD sufferers are able to achieve remarkable benefits.

What are some of the statistics of the Phase II studies?

Of the 107 people that were in our Phase II studies in Switzerland, Israel, Canada, and the US, 23% of our placebo group no longer had PTSD at the end of two therapy sessions and nine non-drug psychotherapy sessions. This is our placebo group! Which indicates that our therapy by itself is fairly—23%—effective.

When you add MDMA to that it’s over twice as good—over 55% no longer had PTSD after just two sessions. For some people the trauma is so great that they’ve become highly disassociated and need a third session. The success rate goes to 61% after three sessions. This is measured two months after the third session. When we look at the one-year follow-up after the third session, then the recovery rate jumps to two-thirds.

Two-thirds of long-term PTSD sufferers cured after three sessions is a staggering statistic.

People talk about DMT or 5 methoxy-DMT and other drugs that take apart your sense of self and have these profound spiritual aspects. Or even LSD or psilocybin, where most of the processing is done as a different form of consciousness. With MDMA you can be engaging in a highly verbal exchange (usually with two attending therapists—one male and one female) and keep this logical train of thought where there’s this deepening of the emotions and a sense that all of it is occurring in the present. This brings an emotional courage to look at difficult things that happened in the past—creating a mechanism called fear extinction and memory reconsolidation.

The basic idea is if you’ve got PTSD and you remember a trauma associated with fear and anxiety, every time you remember this trauma your brain is patterned to reconsolidate and re-create that painful memory. But when you break that pattern by recalling the memory when not feeling fearful, it is played back in a safe tone. It’s repeated as “not happening now” and “not traumatic now.” That seems to be the key to healing.

What’s shown is that there’s something durable about these changes. In our study with veterans, firefighters, and police officers we tested 30 milligram doses, 75 milligram doses, and 125 milligram doses. We were surprised to see the 75 milligram group did best. Yes, we’ve demonstrated that there’s something therapeutic going on with MDMA, which is now a hot and popular tool that neuroscientists are legitimately trying to figure out.

There’s the whole serotonin factor and the serotonin dump thereafter. This isn’t a free ride.

Everything is cost and benefits, and everything carries risks. It’s not just serotonin, but it’s dopamine and norepinephrine as well as oxytocin and prolactin, the hormones of nurturing and bonding. In our method we organize patients so they do the treatment during the day and then sleep overnight and have an enforced rest day where they meet the therapist for more integration work. Then somebody comes and drives them home; they can’t drive themselves. This reduces the feelings of exhaustion and burnout.

Often people who use MDMA recreationally do it at night and don’t sleep and then have to do something the next day without rest or integration, and that’s when they start feeling worse. Whereas in the therapeutic approach, the user is looking for any experience that the psyche brings forward without expectation, the party user is looking for a positive experience. And this positive experience will wear off. In the therapeutic approach the experience that comes into focus may be traumatic and horrific, but it’s being processed rather than resisted.

We emphasize that it’s not about the experience itself but more about the whole package of preparation and then integration. It’s the integration that ultimately changes the baseline state. That’s why people make incredible changes in just one session. For example one of the vets in our study was still suffering from PTSD in a major way years and years after his tour in Iraq. He had also been hurt and was taking opiates for pain. Under the influence of MDMA he realized that there was something positive inside the negative. Specifically, his PTSD manifested as a sign of loyalty to his friends that had been killed or wounded. In a way, his suffering was on their behalf and was his way of staying connected—that he wasn’t ignoring his brothers and sisters who had been destroyed or hurt in the war. The connection and allegiance he felt was the good part, but then he realized that they were all either dead or wounded and that they wouldn’t want him to throw away his life for them. They would want him to live, and the proper way to honor them would be to live as fully as he could and not stay debilitated by PTSD.

Then he recognized that the opiates he was taking were more for escape than for pain and that he didn’t need them anymore. Then he said, “I don’t need MDMA anymore either I’m done. I’m withdrawing from the study. I’m cured.” He figured it out by himself—not by the guidance of the therapists. This gives an insight into the power of MDMA and how things get frozen. Sometimes we need some perturbation of the system to see in a different way.

Am loving the irony that you’re this ex-hippie draft dodger now working closely with the military.

[Laughs] I know. One thing is to be a conscientious objector—to get that status you have to be against all wars. That’s the way it was written—you can’t just pick and choose. I’m not against all wars, I was just against that [Vietnam] war and was willing to go to jail in protest. What’s funny is that back then, marijuana was associated with anti-war protesters while beer was the drug of choice for the pro-Vietnam crowd. I am not a drinker, and at my core I identified early on as a counterculture drug-using criminal. My whole life has been trying to get over that, to be mainstream rather than counterculture, to be accepted and legitimized. So my alliance with the military feels like it’s healing a split. Also, what’s always been clear to me is that we do need a military. We just don’t need an aggressive military that’s doing things that don’t make sense.

Where did you grow up? What was it like?

I was born in the Chicago suburbs—Oak Park and raised in Skokie until I was 12. My parents were traditional left-wing Jewish liberals. We lived in such a Jewish enclave that when I was 6, I literally thought the whole world was Jewish. [Laughs] My parents still tell the story about when they tried to break the news that not only was the whole world not Jewish, but Jewish people were very much a minority. I remember thinking “What if they’re right? What if Jesus is the only way? Then I’m screwed.” But I was raised in a very loving and supportive family and came to understand I was the product of several generations of refugees that escaped to America to avoid prejudice and pogroms. On my mother’s side in 1880 and on my father’s side since 1920.

On my mother’s side it was the classic rags to riches story in that my great-grandfather had a rags business and turned it into a successful paper business. In the 1920s he moved his whole family to Israel and started building orange groves. They were very Zionist, and I had this whole connection to Israel. On my father’s side they barely had enough to survive but managed to raise a doctor. As the only male child, my father knew from the age of 3 or 4 that he had to be a doctor.

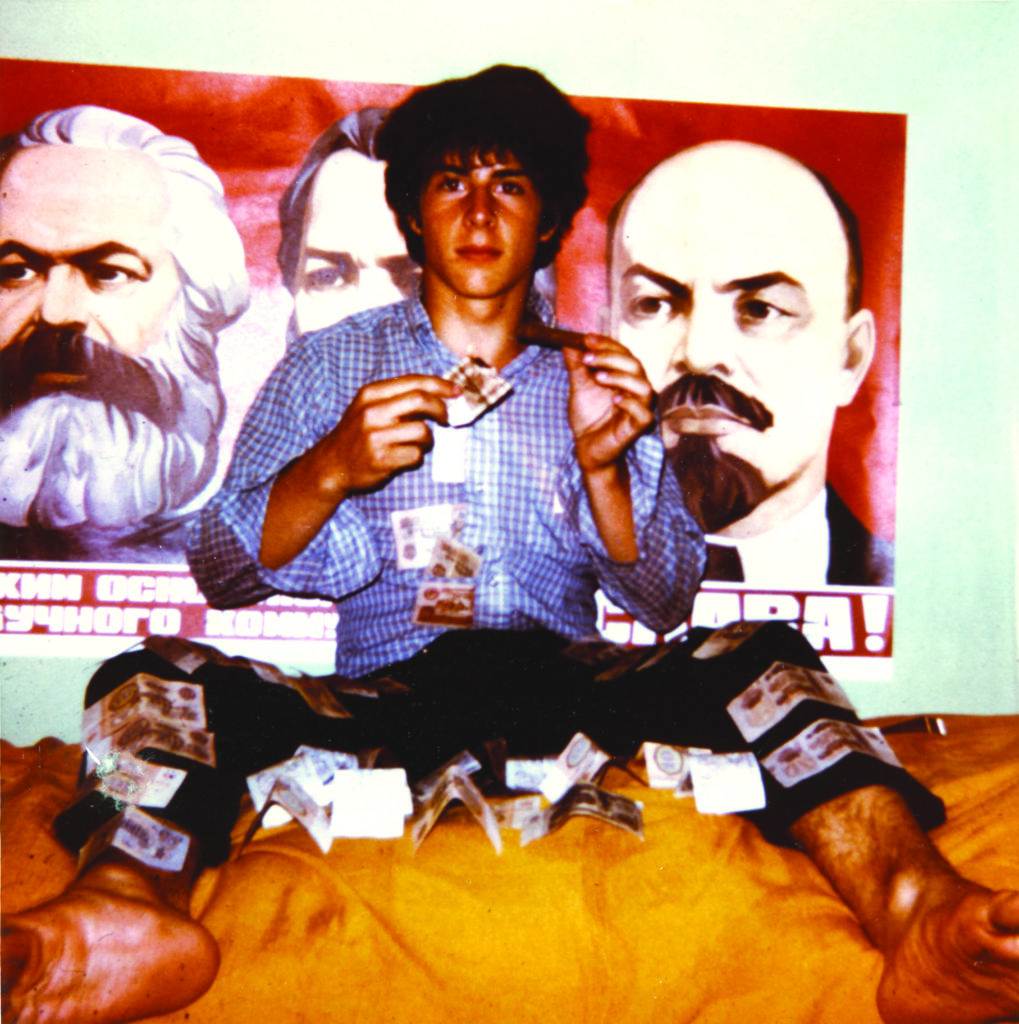

On my mother’s side I had relatives that were in the Irgun, the underground terrorist gang that fought against the British occupation. They buried guns in the family’s orange grove. I was educated from a very young age about the founding of the state of Israel and the Hitler Holocaust. At the same time, my family’s financial success gave me the privilege of knowing that my survival was intact and I didn’t have to compromise to pursue a normal job. I was freed to look at deeper survival—survival from prejudice. I grew up with that relative ease but also within a disturbing, psychologically tumultuous era. Not only was I rooted into the aftermath of the Nazi Holocaust and the creation of the Israeli state, but I grew up during the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Soviet arms race—and Vietnam.

How did that inform you?

I came to see that it was not just external enemies, whether the Nazis or the Soviets, but human psychology that threatens the earth. I learned that our psychological problems are key. I observed the psychology of our own government and its projections—about conflict, killing, war—and saw that it’s nuts. It led me to think strategically, “What would be the most important thing I could do?”

I was impressed by Ken Kesey’s book One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, especially when I found out that part of it was written on LSD. That beautifully written book started me to question all the anti-LSD propaganda. If that magnificent work was produced under LSD, then maybe LSD wasn’t so bad. I had previously believed the propaganda that a few doses made you crazy and caused chromosome damage. Kesey’s book prompted me to try LSD in my first year of college, which helped me feel things—sometimes very scary experiences that I didn’t have the ability to process or let go.

Another book that influenced me was John Lilly’s Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer. Lilly invented the flotation tank. His book is based on the LSD research he did in the fifties and early sixties funded by the navy. He would take LSD inside the floatation tank and start thinking about his mind as if it were a computer and how information and feelings are processed. I too was intrigued by these tools to get into the psyche. My friends and I created these sensory-deprived environments and started doing LSD in them.

Ah . . . like that movie Altered States with William Hurt. I loved that one.

That was it. I ended up thinking, “I need to purify myself.” I need to become a more effective agent. At the same time I saw the backlash of Nixon in 1971–72 and his crushing the counterculture and the continuation of the Vietnam War, and the failure of the peace movement to end it. Timothy Leary went to jail, and I too was also anticipating going to jail because I was sure they’d catch me for not registering for the draft. So I ended up having all these difficult LSD experiences and went asking for help to the guidance counselor at college. He pulls out a copy of Realms of the Human Unconscious by Stan Grof, in manuscript form, before it was even published, and recommends I read it.

Wow!

Yes, wow! I didn’t realize the extent of LSD research that had gone on before but now had been shut down. Science had been looking at mysticism and spirituality and about the ways in which you could have the spiritually unitive experience, the common ground—that we’re all common—that we’re all children of the earth, sharing as humans with more in common than we have different. I thought these spiritual, mystical experiences that reveal the breakdown of the us-them dichotomies are a massive mechanism for social change. The oneness of it all contradicts notions that the Jews over there are the problem, or those Gypsies, or those gays but that we have to be more open with other people, not kill them. That we have to be more careful with the environment.

Stan’s book wasn’t just all these abstract spiritual ideas. He had put this into a therapeutic process that had grounding. It asked, “Are these people getting better? Are they getting over their fear of death? Getting over their addictions?” And I thought, “This is it! This puts it all together for me. This is my direction!” I wanted to become a psychedelic therapist.

Is this your long way of telling me what you want to do when you grow up?

[Laughs] Yes. What a long, strange trip it’s been. After meeting Stan Grof in 1972 I set out to be a psychedelic therapist, and I hope to be one 5 years from now—50 years later. I do sit with people every now and then, but I don’t have a license. Along the way I saw that the path was always blocked by politics, so I got into politics. This is why I went to the Harvard Kennedy School. It’s amazing that I even got into that school. I was the token left-wing hippie they let in that year. When I got there I started thinking about things in the big psychological picture, like social psychology. I saw that public policies were sick and needed a form of psychotherapy. How do you change the mindset of large social groups about certain things? You approach it in similar ways as a therapist.

Unlike many of your psychonaut predecessors, your spiritual path didn’t gravitate to Eastern philosophy as it did most famously for Ram Dass, for example.

No. Ram Dass and Leary focused on the Tibetan Book of the Dead and psychedelic prayers. Ken Kesey and the Grateful Dead and the Merry Pranksters founded their own psychedelic culture using their own elements. The Beatles got involved with the Maharishi and Transcendental Meditation.

I was so awkward and shy around girls at that time, but there was this gorgeous girl in college who taught TM, so I thought, “Okay, maybe I’ll get to know her by studying this.” When she decided not to sleep with me, I thought, “I don’t really like this meditation.” [Chuckles]

[Laughs] The meditation didn’t pay off.

No it didn’t [chuckles] and I still don’t meditate. I always felt there was a selfishness in the urge for transcendence and individual salvation. There was something I didn’t like about the idea of getting off the wheel of life while the rest of the world suffered. What about everyone else?

I was the oldest of four siblings, and the key moment for me growing up was going to be my bar mitzvah. I just really believed it was going to be my spiritual transformation. I had no older siblings to break the news to me that it wasn’t. After my bar mitzvah I remember lying in bed thinking, “I’m not any different. This didn’t do it.” Then I thought, “Wait, this must’ve been a busy Saturday, with a lot of people getting bar mitzvahed.” I figured God was very busy but that he’d get around to me. I kept waiting and waiting, and then after a week I’m like, “It’s just not going to happen. Now there’s another Saturday, and holy crap it’s just not going to happen.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] Still waiting. So you’re not enlightened, and you’ve yet to become a therapist, but you started MAPS in 1986. Can you briefly describe it?

It’s a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Santa Cruz with about 25 full-time employees, of which many are refugees from the pharmaceutical industry. Our donating membership of about 2,500 contribute toward our research and education. We’ve raised $40 million since 1986. We just trained 84 therapists to work on Phase III in 14 locations—42 male/female co-therapist teams.

We’ve a vision that involves actually selling MDMA by prescription someday if it’s legalized as a medicine. We just had a very successful and large sold-out conference at the Oakland Marriott and Convention Center. People came from all over the world. I am really jazzed about the conference.

It was great. You’ve become a skilled fundraiser. I saw that David Bronner just contributed $5 million.

One million dollars a year for five years is a gorgeous expression of the values of David’s grandfather, the founder, Dr. Bronner, who developed a mystical philosophy of “All One” in response to the horrors of the Holocaust. David’s leadership on the board of directors and his donations are transformative.

I love that psychedelics and cannabis are available for medicinal purposes, and I am okay they’re on a path to being decriminalized, but as a parent of a teenager I am also very frightened by their easy availability. Aren’t we opening Pandora’s box too far?

From my perspective it’s less about age limits than it is context. The problem is, you get teens doing drugs without talking to parents or elders but having it with their peers, who get impure drugs and don’t know what’s going on. In our family we have three kids, and because of my work my kids were exposed from an early age. When our kids were bar and bat mitzvahed, my wife and I said to them, “If you want to try marijuana or MDMA come to us, and we’ll do it with you.” All three said, “We’re not ready.” So that was an effective antidrug strategy.

When my daughter turned 16 she came to us and said, “I want to try marijuana and I want to try it with you guys first.” My wife said okay, but she wanted me to do it. She didn’t want to be there because she thought that would condone it even more. So my daughter, whose name is Lilah, and I and her older brother Eden, who had already tried marijuana, went upstairs and had the most delightful four hours where I gently introduced her with the vaporizer, listening to music and getting high gradually. Subsequently, she’s also tripped, but she’s also a great student and has a really healthy relationship with drugs and seems to now prefer alcohol to marijuana. So I think it’s all unique to the family dynamic as to what feels appropriate.

In Amsterdam where you have these coffeehouses, the percentage of young people using marijuana is lower than in America. From a public policy perspective, my view is that these drugs should be legal for adults and illegal for minors, with the exception that parents can decide if they want to give it to their own kids. Already 23 states have laws that parents can introduce alcohol to their minors to educate their kids how they want.

That youth’s brains haven’t fully formed until around 25 seems a mitigating factor.

Interestingly, the FDA is requiring us to conduct MDMA studies with traumatized kids in pediatric populations as part of the approval process. Yes, their brains haven’t formed, but you could look at that in different ways. Let’s say you can open up this “empathy track” with MDMA, this self-acceptance—better they get that earlier than later. Look at all these kids that have social anxiety or are traumatized. Look at all the kids who are prescribed methamphetamines for ADHD. It’s a political argument, but we’re stuffing them with knowledge and information and experiences, and we give them medicines all the time. If we can layer a spiritual experience or an experience of love and connection, that seems more healthy rather than unhealthy.

The fact that their brains aren’t fully formed until 25 is the last argument of the drug warriors who say we should block everybody from having these drug experiences. We don’t block them from computers or from horror movies. If you look at cultures that have successfully integrated drugs, such as the Huichol Indians with peyote and the various churches that use ayahuasca, they don’t have age limits and often include 9- and 10-year-olds with the elders, with the young people generally using lower doses.

What do you say to people who read this and think, “But isn’t the point of life to find contentment in a drug-free state?” Why so much emphasis on mind alteration?

For many people one of the most efficient approaches to enhancing a baseline state of contentment is through the use of psychedelics. When used therapeutically and/or spiritually, the process involves conscious preparation, the experience itself, and integration. When used in this way, psychedelics can be a great tool to enhance the nondrug state, in my opinion.

The unbridled use of psychedelics gets a bad rap, as people go off the rails at raves and festivals. MAPS successfully created the Zendo Project as a kind of on-site psychedelic first aid. Can you describe it more?

This is where the backlash comes as we expand psychedelic research. The last holdout is worried parents protecting their kids. The Zendo Project provides harm reduction and support services at festivals and events. It started in 2002 when we went to the Boom Festival in Portugal and in 2003 when we went to Burning Man for the first time. It is a way to train therapists to make these environments safer and help people who get in over their heads tripping and combining different drugs.

It was important to me that we create a model for a post-prohibition world where therapists help process with people who get deep into their emotional problems in these contexts and reduce tragedies, hospitalizations, and arrests that then become evidence for why the drugs should stay illegal. The Zendo Project is present at Burning Man. We’ve done it at raves in Israel, in Costa Rica, at Africa Burn, at a bunch of Lightning in a Bottle gatherings. I think it’s one of the most important things we’re doing.

Not to be cynical, but from my vantage point publishing Common Ground, I hear about a lot of different panaceas. Yours is psychedelics, but if I talk to someone else they might advocate for superfoods or Tantra or meditation or something else. If more people attended yoga classes, there’d be world peace. What do you say to critics who think Rick Doblin is myopic?

I’d say, “I agree.” The TM people said that if only 1% of 1% of people meditated at the same time, that would trigger a tipping point. Artists say, “If I can just create this beautiful piece of art, that will help people feel.” I’m saying, “Yeah, if you’re an artist and that’s your greatest passion, you shouldn’t drop it all to become a psychedelic therapist.” There are so many different areas of focus, and everybody has to determine “Where is my point of leverage? Where can I be most effective?” I think the psychedelic community can help make a crucial change in consciousness—which is at the core of everything. I’ve been laser focused on this despite having confronted massive opposition.

A great sage once advised me that if you’re doing missionary work—which we all are doing in a sense—don’t hold your breath. Don’t expect quick results. Any final messages to Common Ground readers here by the bay?

That it’s taken 50 years to integrate what happened in the sixties. Now, if we’re careful and tune into the fears and the anxieties of the bigger culture like for the safety of our kids—we can collectively find a soft landing for psychedelics in our culture. We’ve come a long way with similar endeavors, whether it’s alternative health modalities such as birthing centers and hospice centers and yoga and meditation and mindfulness—or visionary art. These have integrated into the mainstream, but we haven’t yet integrated psychedelics themselves. We’re getting close.

I think readers should watch for pockets of fears and anxieties and discern what’s legitimate and help us collectively address these. If you’re a psychedelic user, be responsible. It’s not the panacea, but it can solve a lot of problems. Fifty years is a blink of an eye. Don’t be scared to have long-term strategies and long-term plans. It’s a human right to explore your consciousness.

Rob Sidon is editor in chief and publisher of Common Ground.