The Practical Wisdom of the Silent Monk

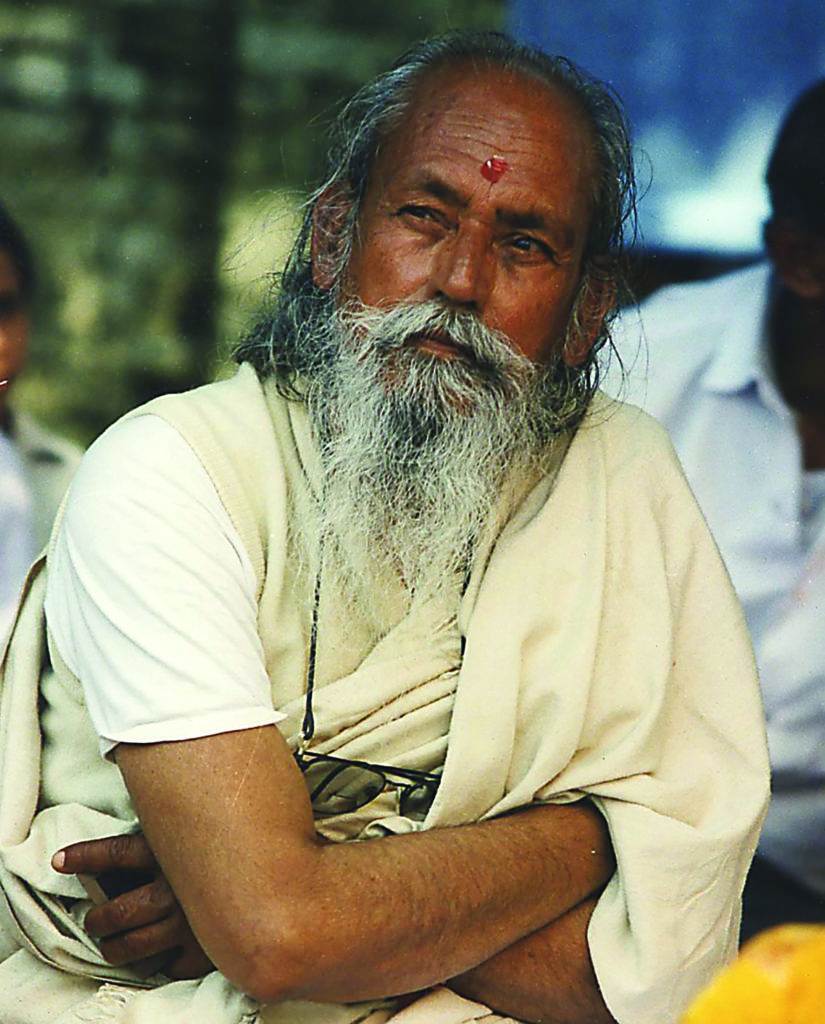

Baba Hari Dass, the silent monk from the foothills of the Himalayas, passed away on September 25th at the age of 95. Babaji, as he was affectionately known, began practicing silence at age eight and took a final vow of silence in 1952 at age 29. Often asked why he was silent, he would jokingly write on his small chalkboard, “To avoid fights.” The longer explanation was that not speaking conserved energy for spiritual practice. Silence helps quiet the mind and brings peace.

I met Babaji in 1974, and while I never heard him speak, his words on the small chalkboard have had a lasting impact on me. He was able to answer complex questions with a few concise words.

Babaji began his life as a monk as an eightyear-old after leaving home to join a gurukul, a residential school where he was steeped in the yoga traditions. He continued to practice in different isolated places and eventually built several ashrams and temples in northern India. Approaching 50, he left those behind and soon thereafter two American students invited him to California. In 1971 he arrived unheralded and silent at San Francisco airport where he was greeted by the same two students and Ruth Horsting, a soon to be retired art professor from U.C. Davis who had just tragically lost her son. Ruth, who became known as Ma Renu, became his sponsor.

After living for several years in virtual seclusion at Ma Renu’s retirement home in Sea Ranch, Baba Hari Dass became known to a number of interested young yoga students. Eventually the group grew to the point where it hosted yoga retreats and eventually formed the Hanuman Fellowship, a non-profit organization which to this day holds all that was created by Babaji’s inspiration. This includes the California-based Mount Madonna Center, Mount Madonna School, Mount Madonna Institute, and Pacific Cultural Center, as well as the Sri Ram Orphanage in India and the Salt Spring Center near Vancouver.

Babaji was deeply knowledgeable about the philosophy and practice of yoga, which was gaining popularity in the West in the ‘70s. He was also one of the earliest proponents of Ayurveda, and is known for initiating some of the first workshops in America at Mount Madonna Center.

Being silent, Babaji taught by his daily example. One day when walking alone with him at Mount Madonna I thought of a question—“How do you do all that you do?” He stopped, took out his chalkboard, and wrote, “I have my discipline and I stick to it as close as I can.” Then he walked away. At first I thought, “How simple.” Then I thought, “How difficult!” This also left a lasting impression.

Babaji’s discipline included teaching yoga practice and philosophy, as well as writing commentaries on the Yoga Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita. He also wrote children’s stories, as well as comedic teaching dramas about the search for liberation in a world full of illusions and scoundrels. Another remarkable part of his weekly discipline was building rock walls at Mount Madonna. Thursday and Saturday, rain or shine, he led the “rock crew” in building Himalayan-style rock walls. Anyone was accepted on the crew. Some learned how to place the stones while others gathered small rocks for backfill. Some shoveled dirt. This exemplified a core teaching of his about communal life: “It takes big rocks, small rocks, and dirt to make a wall”—a reminder to see the value in everyone.

Babaji’s work ethic was legendary. I remember when we were renovating the town center in Santa Cruz, standing with him and a co-worker at the end of a long day. I noticed through a small crawl hole under the aging house that overgrown vines had completely filled the space. I turned to my co-worker and said resignedly, “I guess we’ll have to deal with this at some point.” When I turned around, only Babaji’s feet were sticking out from the crawl hole. He had gotten on his stomach and wriggled in and begun pulling vines. At some point translated to right now—another hallmark of his exemplary style.

Babaji’s discipline also involved playfulness with the children of the community. He played volleyball after workdays and made himself available to consult and provide advice and support. His aphorism, “Work honestly, meditate every day, meet people without fear, and play,” remains emblematic of his core philosophy.

Babaji accepted whoever came and did not demand adherence to any particular belief system or practice. He often described yoga simply as the “development of positive qualities.” While assiduously self-disciplined and hardworking, he never imposed his teachings or beliefs on others. If people were curious and asked questions he would respond. He would conduct classes but never required attendance. When it came to work he wrote, “Karma yoga (selfless service) is a self-chosen thing.”

I believe that between his silence and the insightful words on his chalkboard he effectively conveyed substantive wisdom. His uniquely quiet mind understood what transpired around him and saw what was needed. In this fashion, he inspired generations of students.

When once asked about his intentions he replied, “To make a few good people.” He also reminded us that the teacher could only point the way. On his board he wrote, “I can cook for you but I can’t eat for you.” The gift he brought to those who knew him was his vast knowledge, experience, and self-discipline, but it was by his example that the miracle of his inspiration flourished.

Sadanand Ward Mailliard met Baba Hari Dass in 1974 and became a student who helped found and build Mount Madonna Center in Watsonville, CA. MountMadonna.org