Carl Jung and the Practice of Active Imagination

If you associate Carl Jung with staid, stodgy sessions in closed, quiet offices or with the institutional conformity endemic to academic white men, think again. All you need do is look at Jung’s art and read about his explorations into the swirling psychedelic spaces of liminal mind and you’ll soon see him as an inspired mystic who used creativity and explorations into some of the stranger parts of the psyche to find healing and mental balance.

In 1912, Carl Jung dramatically split from his mentor, Sigmund Freud, an acrimonious breakup that sent Jung into a psychological tailspin. Jung felt he had been, in his words, menaced by psychosis. The process of digging himself out of that hole produced what Jung considered the prima materia (an alchemical term that refers to the starting point of transformation) for his lifelong work. Jung felt his most important work was first conceived during this period.

Jung considered creativity and imagination necessary to achieve psychological balance, as well as to accomplish meaningful work. To embark on the path to healing, Jung taught himself to linger in the zone between consciousness and unconsciousness where he could let unconscious symbols and images arise while consciously monitoring the experience. Jung felt he could bridge the gap between his deeper intuitive psyche and his logical waking mind by using the creative process to actively engage what arose in his unconscious, then integrating it into his conscious life. He called this process active imagination.

Although Jung didn’t clarify how he began active imagination, some writers and historians think he accessed the realm between consciousness and the unconscious by entering hypnagogia, the dream space between waking and sleep. We know from Jung’s autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, that he did experiment with this extraordinary mind state.

We all naturally experience hypnagogia. As you fall asleep at night or into a daytime nap, or struggle to stay awake when you’re exhausted, you pass through a swirling hallucinogenic, psychedelic realm that feels partly like a dream and partly like awareness. That’s hypnagogia, the kaleidoscopic, free-associative dream state that artists, scientists, and thinkers of all sorts harness for various purposes, including creativity. In the morning, you surface from sleep through the swimmy realm of hypnopompia, the twin of hypnagogia that emerges on the other end of sleep. Together, these two states are called liminal dreams.

The word “liminal” comes from the Latin word limen, which means threshold or doorway. Liminal dream states lie between waking and sleep. In hypnagogia and hypnopompia, you straddle conscious and unconscious zones, experiencing both at the same time. This allows you to simultaneously access your logical, observational mind and your intuitive, dreaming mind, so you can drop into your unconscious but retain enough conscious awareness to bring the experience back into waking life.

It’s easier to get into hypnagogia, since you can access it any time using naps. Just settle into a relaxed position when your energy naturally dips, perhaps late afternoon or in the evening. You can also do it in bed at night, but then you fall asleep so it’s hard to remember what happened. Once you’re comfortable, breathe slowly and deeply, allowing your body to relax into slumber while giving your mind enough mental juice to stay awake. The trick is to sink into the hypnagogic dream while retaining enough awareness to not fall asleep. For more detailed exercises to help you find hypnagogia and hypnopompia, visit www.liminaldreaming.com.

Over the years, analysts and other practitioners in Jungian traditions have used hypnagogia (or hypnopompia) as the starting point for active imagination. In liminal dream states, the mind drifts with a minimum of direction from the conscious mind. We’re unconscious enough that our reasoning, controlling ego lets go of its grip and we encounter deep elements of the mind, yet we remain awake enough to perceive and remember what arises. This allows symbols, images, ideas, and other elements of the language of the unconscious to surface into conscious understanding.

In the process developed by Jung then fine-tuned over decades, active imagination practitioners begin by drifting into liminal zones and immersing themselves in a swirling stream of images, memories, story fragments, or symbols from the unconscious. They then allow whatever arises to manifest via creativity. This creates a dialogue with the unconscious, allowing practitioners to develop a relationship with what lies in the deeper parts of their psyches. Jung believed that learning to understand and communicate with the unconscious naturally resolves many psychological issues.

This Active Imagination exercise is based on a version developed by Robert A. Johnson. A Jungian analyst and prolific author, Johnson wrote several 1970s best sellers about psychology. In the 1940s he studied with Krishnamurti in Ojai, California, and in the 1950s he established a Jungian analytical practice, which he closed in the early 1960s to join a Benedictine monastery. He resumed his practice later in the 1960s and lived for decades as an analyst, author, and priest.

Active Imagination Exercise

- Set the stage for a creative process. Keep something handy nearby: paper for drawing, a pad to jot down ideas, clay for sculpting, paints, collage materials, a video camera to capture movement, etc. Keep in mind that the creative process is the point of this exercise, not the end product.

- Get yourself into a hypnagogic state. You can also do this with hypnopompia, but hypnagogia is an easier starting point.

- Sink into the flow of the liminal dream state with the intention of encountering meaningful symbols, images, ideas, or impulses. Do not attempt to control or manipulate the experience, but don’t allow yourself to simply drift into fantasizing. Watch what arises with the idea that your unconscious can communicate with you, and can teach you about the contents of your own mind.

- Once something intriguing appears, or as soon as you begin to transition out of your liminal dream state to waking or sleep, begin the process of giving form or expression to whatever stood out for you. Start a drawing, mold clay, record yourself singing or dancing—whatever helps concretize the gifts of the unconscious into waking life.

- Allow the creative process to become a meditation. As you write or paint or dance, think about what you perceived and why it felt important to you. Ask yourself what message your unconscious had for you. Let it become part of your waking consciousness.

- As you continue to engage with your creative process, you may want to reenter the liminal dream state to refresh the symbols, images, characters, or whatever it was that caught your attention. Do not hurry. Allow the process to take however long it takes, whether that’s hours, days, or months.

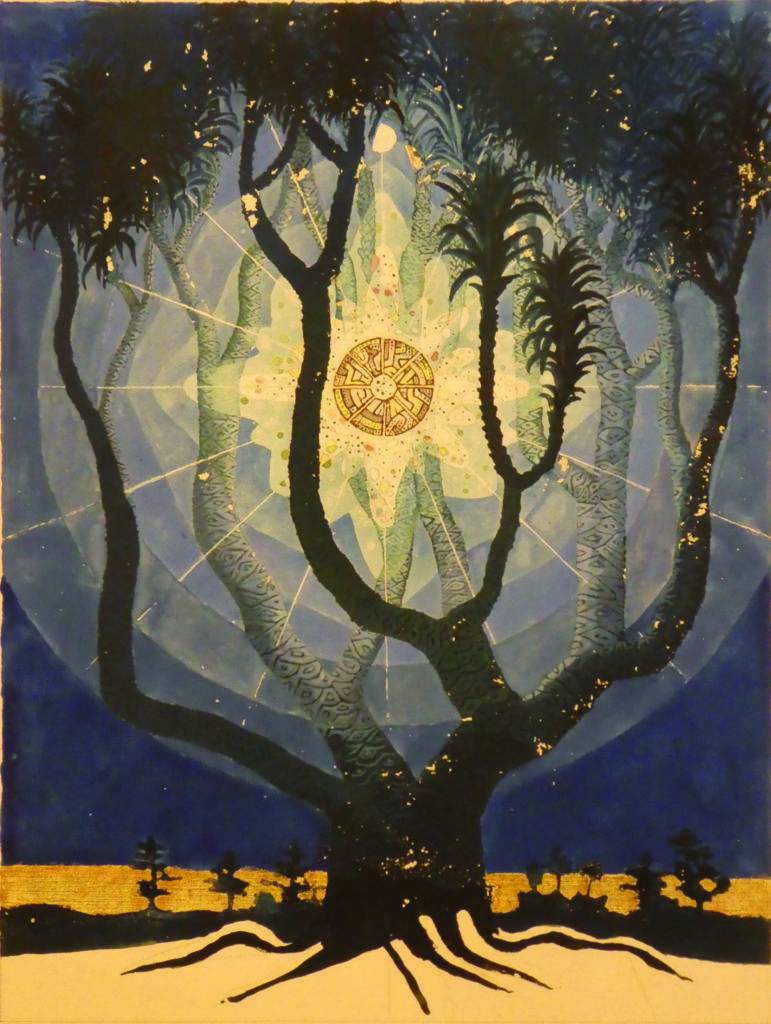

During the emotionally chaotic time in his life when he developed active imagination, Jung began recording his experiences in a series of journals that he called his “black books.” At the outbreak of the first world war, Jung came to see his visionary journeys as culturally relevant, not just personally important. He began transcribing his visions, along with commentary, onto parchment. He then commissioned the creation of a red leather book into which he interleaved the parchment pages. He continued to fill the book with his astounding visionary art and graceful calligraphy. This illustration of Jung’s adventures in active imagination came to be known as The Red Book. In 2009, a facsimile of the volume was released by Jung’s estate.

Last month, I had the opportunity to see a show called “The Illuminated Imagination: The Art of C.G. Jung” at the Art, Design, and Architecture Museum at UCSB. The exhibition included the original Red Book, one of the black books, and a series of Jung’s other art, some of the most remarkable, and most psychedelic, pieces I’ve ever seen.

For some audiences, I write or teach about hypnagogic or hypnopompic “dream tripping”—using dreams to achieve the kinds of states that people seek with psychoactive substances. Hypnagogia can feel like a psychedelic experience. Some highs are endogenous—naturally occurring within the body. Over the last year or two, popular culture has increasingly embraced the concept that psychedelics can be useful for healing and also to access the visionary, a state that finds expression in creativity, a perspective shift that owes much to Michael Pollan’s work. Yet many people hesitate to engage in the powerful, and also illegal, experience offered by psychedelics. But you can achieve these states using hypnagogia. As I walked through the exhibit, I thought, “Wow, Jung was clearly a hypnagogia tripper!”

We can all have wild, astounding, visionary experiences using solely the natural powers of the mind. When you look at Jung’s art, I think you’ll clearly see that he has visited such realms. Jung believed that tuning into frequencies of the unconscious then approaching them with creativity naturally balanced the psyche. He also felt that anyone could undertake this process. It is an adventure in self that’s waiting for you to embark on it.

Jennifer Dumpert is an SF-based writer, lecturer, and founder of the worldwide dream exploration group the Oneironauticum. She is the author of Liminal Dreaming: Exploring Consciousness at the Edges of Sleep. She posts a daily dream to Twitter as @oneirofer. UrbanLandscape.com