THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JOHN PERRY BARLOW

By ROB SIDON

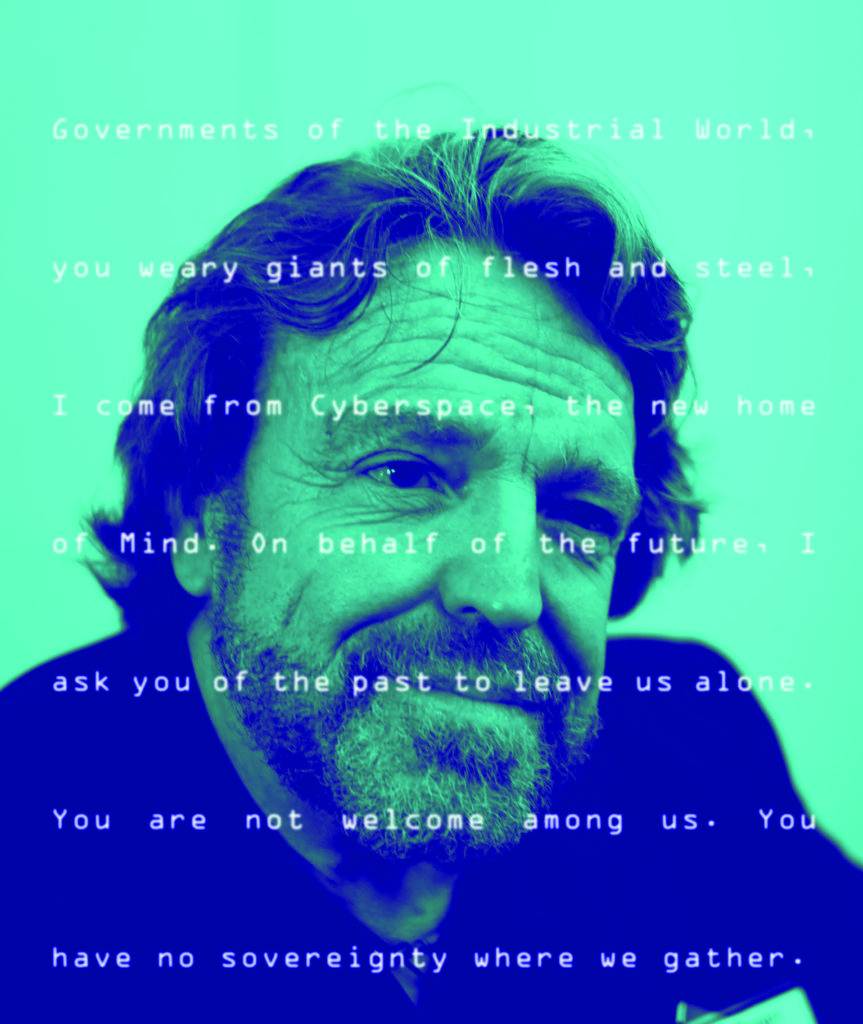

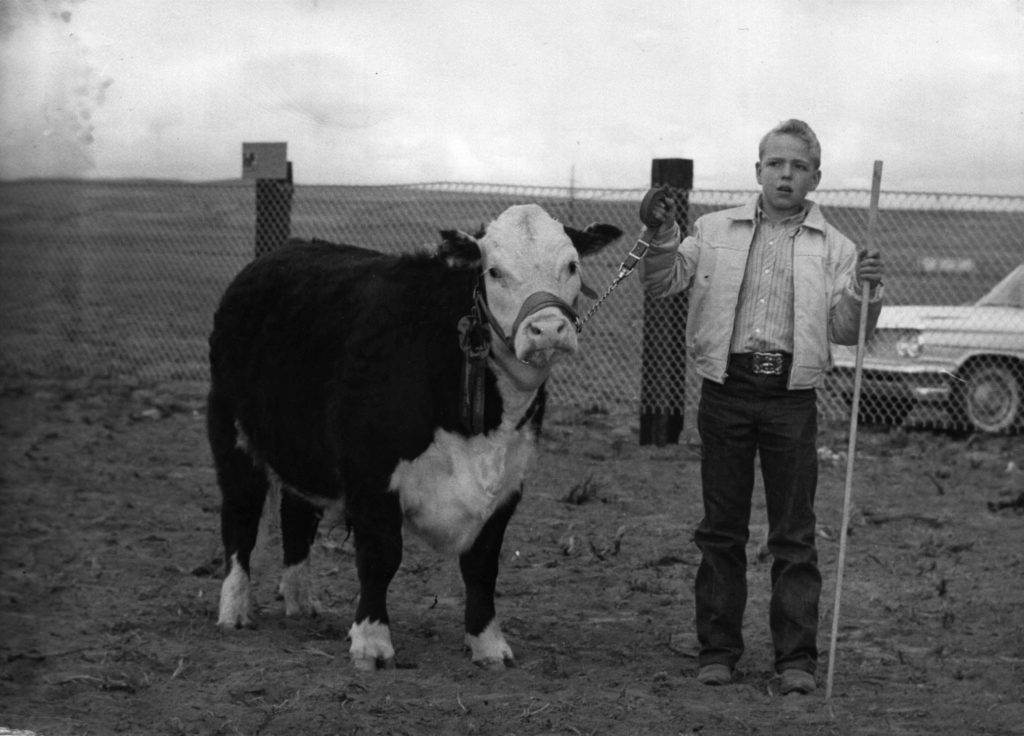

John Perry Barlow is an American poet, essayist, and former lyricist for the Grateful Dead who helped shape the Internet in its earliest days. As a cofounder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Freedom of the Press Foundation, he famously helped coin the term cyberspace and is regarded as the world’s most outspoken cyberlibertarian. As a political activist and consultant, he has been associated with Democratic, Republican, and Libertarian ideologies. A fifth-generation cattle rancher, he was born in Wyoming in 1947 and ran a 22,000-acre property until 1988.

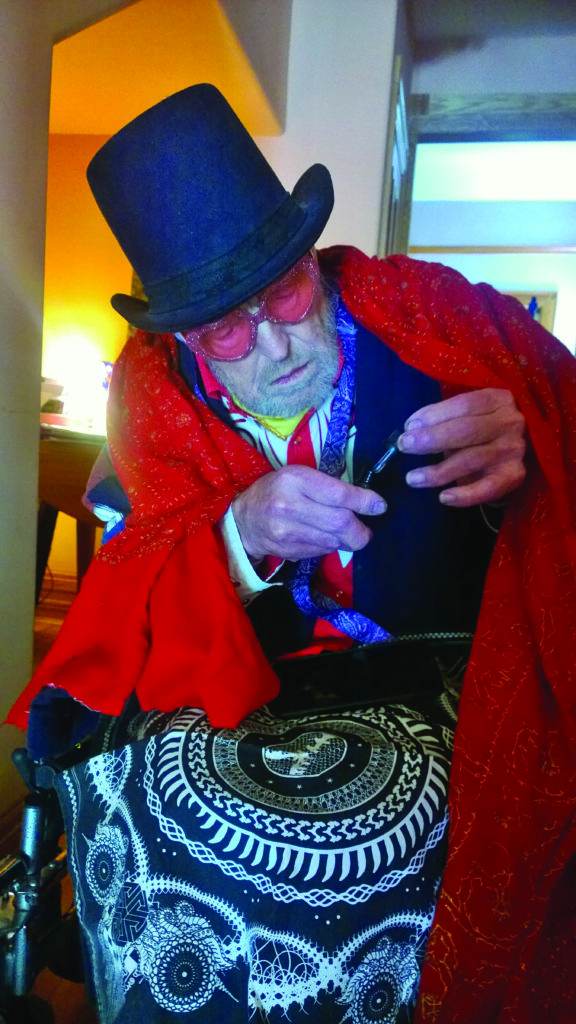

As a result of some painful medical complications, Barlow has been crippled to the point that he was deemed dead for eight minutes before being miraculously revived. We caught up with Barlow in a San Francisco hospital two days after doctors determined his health was too precarious for him to attend the star-studded benefit concert that had been organized for him. Though he was in pain, our conversation covered broad ground including near-death, gratitude, lost love, religion, karma, spiritual philosophy, Mormonism, political ideology, the 2016 election, the Church of LSD, the Internet, and his lifelong friendship with Bob Weir, among other topics.

Our conversation was happily interrupted by many doctors and nurses and orderlies, friends and ex-girlfriends, visitors, well wishers, business partners and attendants, including several of his three daughters—not to mention telephone calls. Suffice it to say, John Perry Barlow is a very loved man whose health status is a concern to many.

Two days ago I attended a fundraiser for you that included an amazing slew of musicians, including Bob Weir, Michael Kang of String Cheese Incident, Sean Lennon, Jerry Harrison of the Talking Heads, and Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, just to name a few. But you were too ill to attend . . . what’s going on, my friend?

Dreadful, I confess. I had a rough go over the last several days. I felt rotten because I couldn’t see this wonderful assembly. This [pointing to his hospital room] is part of something that’s been going on for over a year and a half. I got a staph infection in my blood and went to Stanford Medical after the infection had moved to one of my shoulder joints. Stanford sent me home, but then I woke up with four joints on fire, which began a long saga of horror beginning with immediate emergency surgery. By the time they were done, there wasn’t much cartilage left—which left me pretty much crippled. There’s been an element of the allopathic medicine feedback loop where you have problems stemming from solutions on an increasingly magnified scale. This all didn’t need to happen. If they’d gotten to it while it was only one shoulder I’d be pretty close to fine.

This is our 42nd Anniversary issue. Since you’ve been knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door, I presume you have something to say about gratitude.

As in every other case of the world I am not grateful enough but am working on it. I believe that the secret of life is learning how to accept love. My spine being in essentially two quite distinct pieces and being helplessly unable to walk, I started into a course of study of learning how to accept love—out of sheer necessity.

What’s that been like?

Incredible. Unbelievable people, like Alden [Bevington] have appeared—magical beings as far as I’m concerned. I don’t know how to describe how grateful I am.

Weren’t you declared dead for a full eight minutes?

They’d been mucking around inside my arteries and fixing the infected hardware when they found a gigantic hematoma next to my spinal cord about the size of two golf balls that left serious damage. In the process of stabilizing that and to prevent pulmonary embolisms a clot was sent upstream. That hit me hard. I was wedged and dead as a hammer for eight minutes.

Did you hear Jehovah’s favorite choir [a reference to the Grateful Dead song “The Music Never Stopped”]?

No. Talk about disappointment. It was stone, black, zero, nothing. I was expecting descending rivers of light and mysterious, luminous angels.

All your ex-girlfriends waving at you.

Exactly. My best friend and songwriting collaborator Bobby Weir said, “It may be that you weren’t dead enough.” [Chuckles] That’s a very economical way of putting it, but there’s a lot of positive truth to that. Or—there’s nothing that happens after death. This goes against everything I feel, so I’m not suddenly going to start viewing things that way. The miracle is that I was really dead. They put the paddles on me and gave me a big whack—and nothing. They gave me another big whack—nothing. Finally, this intern on his own initiative hauled me off onto the floor and jumped on my chest with both knees, which cracked all the ribs going into my sternum. And I came back.

That’s a person you’re grateful to.

Ow, indeed. An angel who disappeared back into the crowd. Afterward, I asked, “Who was that masked man?” They wouldn’t let me know, which was odd. It’s been a series of one miracle after another, but the huge irony is that all these miracles have been necessitated because of an error.

What was your religious upbringing?

My father came from a group of Mormons who had been with the early tribes. His ancestor numerous times removed had been one of the people that signed the affidavit attesting the golden plates. They had been burned out of Kirkland, Ohio, and burned out of Malibu, Illinois, and finally settled into what became Salt Lake City in about 1848. So my father, who was an amiable alcoholic, was in the thick of Mormonia. He ran for governor and was gallivanting around the state, drinking and womanizing and having an incredibly good time—not very Mormon like. So I was raised kind of Mormon.

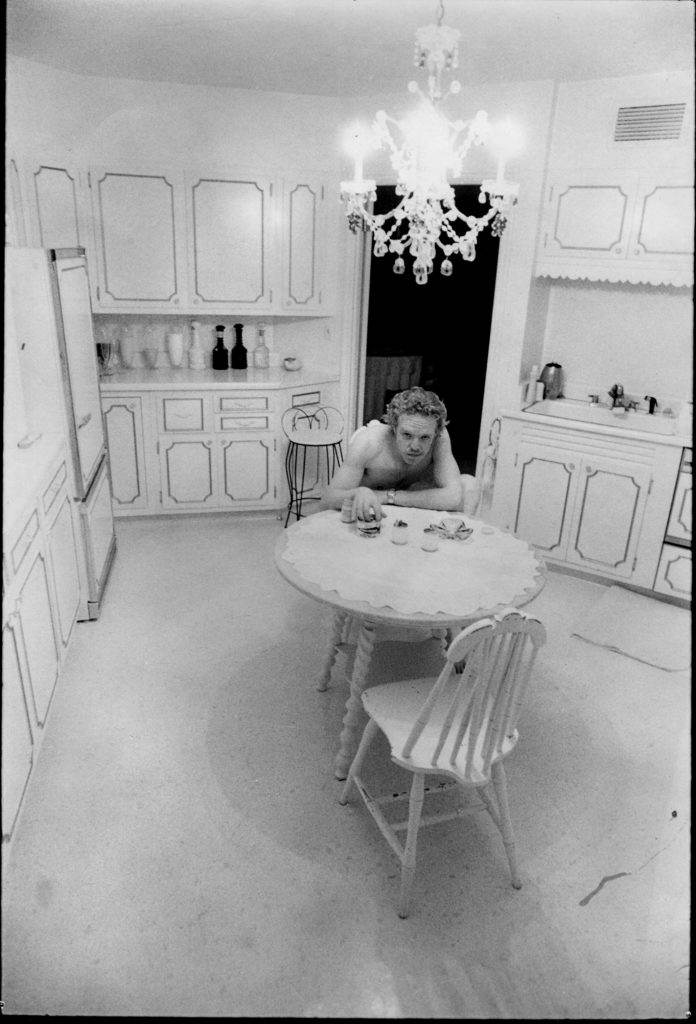

What else about your upbringing in Wyoming informs your life?

Complicated question. I am a fifth-generation cattle rancher with a drinking politician father. My mother was a completely mad narcissist. They were 42 years old before I was born, and I am the only child. The very last thing they were expecting was me! Essentially, I was raised by a bunch of farm animals. When I was about 9 my nuclear family went fishing, and my mother had a fantastic nervous breakdown and checked herself into a mental hospital in Denver. They were giving her electric shock therapy, and when I’d come to see her I could’ve been anyone—which is a little disconcerting to a 9-year-old. I think about some of the things I’ve been through. I’m not complaining. I guess it’s part of my curriculum.

Do you ever feel gypped, karmically—that you’ve been robbed of your Golden Years?

Well, this is not how I thought things would wind up, no. But I don’t think of there being such a thing as a gyp. Consider the alternatives [chuckles]. Years ago, maybe in 1988, when I was in transition, I picked up a hitchhiker in the Nevada desert that I never forgot. He had a sign that said, “Anywhere but here.” He was basically a mess and smelled obviously worse—but he had gravitas. His luck had been different than mine. He was born in the Bronx and been fucked up and shot in Vietnam. He’d told me how he’d recently lost everything because of a dispute with his landlord his apartment, his cab license, his saxophone, his identification papers, his girlfriend, everything.

At one point we stopped into one of those Bagdad Café gas stations with a telephone booth— remember those?—at the corner of the property. I glimpsed him write something on a piece of paper and stuff it in the coin return. So I took a sweep to see what he’d done and found his note that said, “Love forgives everything.” I asked him later, “Why did you write ‘love forgives everything’ on that note at the gas station?” He said “Well, it does. I thought somebody would be looking for money and get my note instead.”

I said, “Now wait a second. The fact that you did that indicates to me that you believe there’s some kind of higher being that you’re working on being one with, right? And he said, “Well yes, I believe that.” I said, “That’s kind of ironic because I don’t believe any of that, yet my life is really pretty good and easier in most ways whereas if there is a God, he’s messing with you very harshly.” He said, “That would appear to be the case, but I think part of why we’re here is so that we can take courses and some of us are taking Astrophysics 406 as I am, and some of us are taking basket weaving as you’ve been.”

So I slowed down to about 25 miles an hour because there was a lot to absorb. He turned the whole notion of karma completely upside down. It created a vision of karma that is much more aligned with how I think it is today—that karma is not punishment. His misfortune had nothing to do with God punishing him but was more likely rewarding him as an advanced soul who was advancing. That made a lot of sense to me and especially subsequently when I lost the great love of my life, my girlfriend. [Weepy] God, I loved this woman so much.

This is the story of Doctor Cynthia Horner, your fiancée.

[Visibly distraught] Completely unexpected. No warning whatsoever. We were going to meet in New York the next day to celebrate her 30th birthday. I put her on a plane at LAX where she stretched out, but by the time the plane landed she had just dropped dead. It was a heart arrhythmia, the result of undetected viral cardiomyopathy.

Wow!

That was in 1994. The story of the hitchhiker had been a big part of my way of looking at things, and when Cynthia died I suddenly realized I had just taken a significant upgrade in the registrar’s office—in the great university of life. Both of us had said we could not imagine living without one another—and we meant it. It turned out we could. But I confronted a new set of challenges that were more difficult than what I’d been previously dealt.

What’s your spiritual path now?

We were just talking about that and this will sound trivializing, but I’m still a full-fledged member of the Church of LSD whose doorway through which I recede in order to experience the holy “who knows?” That’s my term for that thing that I don’t think should be named. Since “It” said it didn’t want to be named, I’m happy to oblige. Anyway, acid seems to be the easiest way for me to get there, though I’m presently working on trying to find other ways since this [points around his hospital room] is no place to be dropping it.

Don’t you have a cautionary message to younger people about psychedelic explorations?

Just do it. That’s facile and I don’t mean to trivialize it, but I don’t believe I know anybody who ever took LSD, or genuine psilocybin, or a couple of other drugs like that—and took them seriously—in some quantity and in the right setting—who would not say that their lives were improved. Even if it was a horrendous trip, they came out of it a different and better person. My generation’s problem with acid was that we got overexcited about it. We thought we were going to get God to jump through the transom in the summer of ’67, and the Age of Aquarius would commence, and peace and virtue would descend upon the planet. That expectation didn’t take into account quite a number of things but it [acid] nevertheless points a way. Once you feel strongly in your being that it’s all connected, that everything is actually one thing—and that what one does to any of it, one does to all of it. That makes it . . .

A good religion?

Yeah. The extent of my doctrine is that sin is that which separates.

You studied comparative religions as an undergrad at Wesleyan University.

At first I started studying physics, since that struck me as a good place to look at the complex relationship with the Holy but immediately ran aground on arithmetic. They had a calculator at Wesleyan that was the size of a bread box, and there was always a line for it. You could do the science on your slide rule, but I didn’t have the patience for that and decided I wasn’t cut out for physics. I took up the study of comparative religion, which was a polygon of courses that I put together myself. They included the study of Islam, Zen Buddhism, and Christian mysticism, which is what I was mostly focused on. And Gothic architecture.

And then you visited India as young man. What was the effect?

Holy shit. India is like the ultimate Rorschach test because it will show you yourself in so many different ways. I was about 20 when I went on a whim, without an agenda or any expectations and stayed for close to 11 months. At one point I did find myself completely by accident on top of a mountain with a holy man who spoke not-very-good English. He was fascinated with automobile mechanics, which I happen to know something about. I spent a hell of a lot more time telling him about car mechanics than he did about Buddhism. It turned out that in retrospect, after I processed it, that we were not far off one another’s mark. I felt this great spiritual longing. I wanted desperately to have that sense of order on a divine scale.

Let’s change the subject. I definitely want to talk to you about politics and all your Internet involvement, but in the meantime is there another question I should be asking?

Did you know Jerry [Garcia]? [Chuckles] That’s the question everybody asks.

[Laughs] I was holding that one till the end. But let’s talk about your involvement with the Grateful Dead.

Well, I’m much more inclined to identify myself as a cattle rancher, or a cyber libertarian, or somebody who spent six years trying to curb a negative fuel. In terms of the amount of natural time that I’ve put into those songs, that aspect of my life—Bobby [Weir] or the Dead is practically irrelevant. For every hour I tried working on a Grateful Dead song—and there was a huge amount of overlap—there was a lot of time where I was out there pushing cattle, or driving a tractor, or any one of a number of things—when I was thinking about Grateful Dead songs in the back of my head. In fact I found that one of the things that was actually most valuable in terms of writing that stuff was having something else that would occupy the majority of my consciousness.

You’re known for a lot of things, as a lyricist, a poet—

I don’t know that I’d call myself a poet. Poets have a special place in life. Robert Hunter is a poet. T. S. Elliot is a poet. I’m a songwriter and not a hugely good one, but I get by. And it’s a good thing I’m there from the standpoint of the Grateful Dead and its decedents, who would have otherwise lacked a hybrid quality that just wouldn’t have been there if it had just been [Robert] Hunter and Garcia—whether my songs were as good as Hunter’s or not. Many of the things that I’m proudest of are things that practically no one will ever know. I mean, I’m the guy who got China online. Stuff like that.

Have you heard Bobby’s new album Blue Mountain? It seems a tribute to the ranching Barlow-Wyoming years.

I don’t even want to talk about it.

Why don’t you want to talk about it?

The reason I don’t want to talk about it is that to the best of my knowledge, I am the first and only honest-to-God cowboy Weir has ever met. And I’m his collaborator, with whom he spent many years on my ranch. So he suddenly decides to make a record of cowboy songs and doesn’t let me know until he’s got it just about done. Which I just think sucks.

You guys are best friends to have a story like that.

It’s exactly what friends do, but it really pisses me off. It strikes me as being very specifically unkind. Not only that, but he does it with some kid whom I like a lot. And I like the record—don’t get me wrong— but he does it with some kid that is completely non-rural. And the other people in his band are suburban. And they all just love the shit out of me, and they can’t figure out why it is that I’m not participating. Bobby Weir has been my best friend since we were 14 years old, but sometimes friends just have to stick it to each other.

Weir describes himself as pathologically antiauthoritarian. It seems you share that trait.

I’d have to say that’s true. I don’t know if it’s pathological. Frankly, I would say normal.

The first time I ever met Weir I gushed how much I loved “Weather Report Suite,” which was on the Wake of the Flood album I bought as young boy in 1974. The lyric “sit inside the rain and listen to the thunder shout: I am, I am, I am.” So beautiful—that’s how I was introduced to the writing of John Perry Barlow.

The whole download. Not a bad way to come in. At least you got the reference.

Can you talk about the earliest days of the Internet? You were right there in Palo Alto, right?

I feel like I was there in retrospect, but there was always somebody that was there before. All those guys—Vint Cerf, Leonard Kleinrock, David Reed—I was right in there with them. It’s a long list, the various uncles of the Internet, which was one of its superb strengths—that it doesn’t have a father. People are constantly showing up at Vint Cerf’s office and want to know where the head of the Internet is. [Chuckles] And finding it difficult to believe that there doesn’t seem to be one. I was one of the first people to notice that this was a space. That it wasn’t just tubes. It wasn’t just like a phone number, but it was a big room. That made a big difference, I think. Also, I think it was important that somebody name it so that it could have a political identity. That would completely change the dynamic in terms of how the rest of the world dealt with it. It would no longer be nameless and placeless. Ironically, the name I gave was even more nameless and placeless.

What was that?

Cyberspace.

You coined that term, right?

Bill Gibson [the cyberpunk science fiction writer] coined the expression [in his 1984 novel Neromancer], but he was talking about something different from what you encountered in real life in 1985. I think the first time somebody used that word in reference to the thing that already existed was in a speech I gave in Dallas in 1988. And it caught on. Bill never felt like I ripped him off; he felt it was advancing the cause.

Who named it the Internet?

The Internet, as a name, just simply grew. First there was ARPANET, which was the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network. Then my friend Dave Farber, who is an exceptionally adroit political character, declared his desire to attach all the computer science networks in the United States into the ARPANET, so he got it changed from ARPANET to combine it with CS-Net. And then it became the Internet.

One of your great achievements is the cofounding [with John Gilmore and Mitch Kapor] of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the digital rights group. What’s the story?

We were trying to keep [the Internet] free, everywhere in the world. We wanted to make sure that if you have something to say, or something you want to hear, or something you want to read, that you can—from the wretched to the sublime. That if you are curious about something, you will be able to slake that curiosity. So that some kid in Mali could learn all he wants about proteomics.

The EFF also brings an alternative attitude about the Internet and about the rights of its users. We help bring the users’ point of view to situations where maybe users are not so organized to represent against some government positions or corporate positions. When Facebook changes their privacy policy, users might not like it but are not very organized to oppose it. So we go talk to Facebook’s lawyers and figure it out. EFF helps act as the users’ voice and for teaching about online responsibilities.

The EFF has clout?

For most of the time that we’ve been involved, it was a small organization with 10 people on the staff at most. But at this point it’s an institution with almost 30,000 members and a budget of $10 million dollars a year and 70 people on staff. It has succeeded beyond my wildest expectations. We worked on search and seizure law and wiretapping. We worked on freeing up encryptions, so people are free to encrypt their messages so that other people and governments can’t read them. We worked on overbroad copyright laws. We worked on privacy issues, freedom of speech. We proposed the Communications Decency Act in court. What we noticed long ago was that every time we turn over a wet rock, there’s another issue wriggling underneath showing how society and the Internet have caused changes. That laws and social mores had not caught up with the changes.

It’s impossible to avoid talking about politics now with the election coming up. Some say your song “Throwing Stones” embodies your opinions.

God, I wish there were a way to escape this tedious election. I think my views come out more vividly in [essays] “The Economy of Ideas” or “The Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace.”

Interestingly, you’re a famous cyberlibertarian, but you’ve also been an outspoken Democrat and a Republican and a Libertarian. Where do you land, politically, today?

I don’t like to think of leftwing and rightwing but of something more spherical because beliefs are scattered—with concentrations of opinion. I’m not comfortable with the leftwing because it’s incredibly authoritarian. I mean, they do it because they love you, or they claim to. They do it because they love control, and one of the best ways to assert control is to pass all kinds of regulations with the belief being that without their gentle, kindergarten-style handling, people could not be trusted with their own freedom. I worked closely with the Democratic establishment, and it’s been really manic. The Republicans at this stage are completely beneath contempt. Do you remember the Know-Nothing Party from the 1800s?

Oh, yeah, from history class.

It’s unbelievably stupefying. How could they do it? I’m stunned. The Know-Nothing Party is reborn! I don’t think there’s much going on except “let’s just get rid of the nigger.” It doesn’t make any difference how good he did, how beautifully he performed, how elegant he was, or how articulate and graceful. The man’s the wrong color to be President of the United States.

You think it’s just a racial thing?

It’s more complicated than that, but I think a lot of what America is about is making sure that there’s always somebody lower on the totem pole—no matter what kind of trailer trash you are. They’re not planning on getting rich; they just don’t want to get any poorer than the next guy. On my father’s side they came over in the 1620s. On my mother’s side they came over in the 1670s, but I don’t feel I’ve got some special right adherent in the fact that my Europeans arrived before their Europeans. So what? The fact is there were actually a lot of people here already. But we just raised hell with those people, partly by just outright killing them. Passing out small pox–infected blankets—you know—a little ethnic cleansing. Yet we’re worried about their terrorism. Jesus, you want to look for terrorists? I know where to find them.

Besides cyber-libertarianism, what should people know about political libertarianism?

I’ve had to redefine my own libertarianism because it’s a great point of view for the world when living on the ranch with the Code of the West. When I moved to New York I started taking a look at things through a different set of eyes and realized during the second Bush administration that it really did matter who was president. I saw that unfortunately the president could make a difference—and a bad one. That kicked the shit out of my libertarianism because it meant I had to be more proactive coming up with stuff that would stop these guys. They were deregulating everything, and the consequence was appalling.

I am sorry you have to go through all this suffering in the hospital. You look tired, but you still got a fighting spirit. Am curious, if with all the pain do you ever think, “Oh fuck it. Let’s just leave this party”?

[Solemnly] Yes, I do. And more lately than usual.

You have a stubborn streak.

I tend not to quit. I mean, I wouldn’t say I don’t quit, but you better beat me up pretty good before I will.

A parting message to readers?

Be kind. Ask yourself if you’re kind. I used to have this roll of little round blue stickers that I would peel off and put on men’s bathroom mirrors that just said Are You Kind? I need to get more of those made. Also, it would be good if people could recognize that things are extremely rarely black or white. They’re almost always some form of gray.

How do you want to be remembered?

I want to be remembered as a brave man who was brave in the service of goodness. And as somebody who was kind, almost thoughtlessly. If it didn’t say anything on my gravestone but “He was a good man,” I would be happy. I’d be dead but I’d be happy.

For what it’s worth, there was a beautiful tribute concert a couple days ago with a lot of delighted Barlow lovers who were happy to be there.

Aw.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.