The Fall and Rise of a Dharma Punk

By

ROB SIDON

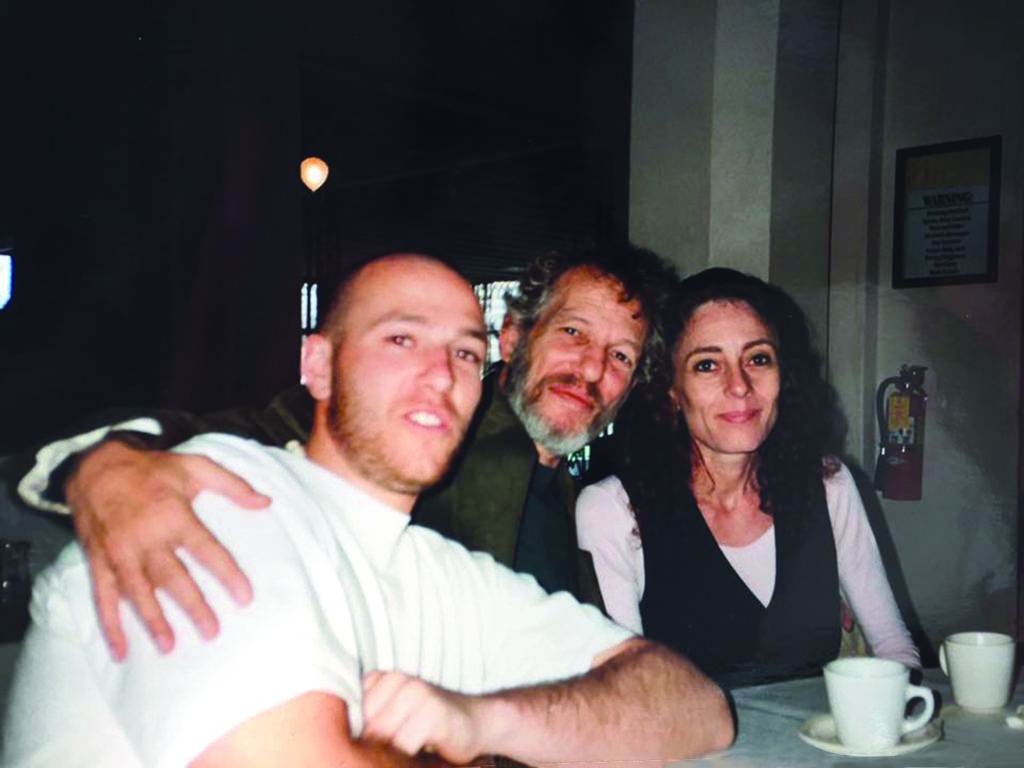

Noah Levine, born in 1971, is the son of the famous author Stephen Levine. Noah discovered marijuana at 6 and LSD at 10. His early experiences led to alcohol, heroin, crack cocaine, and suicidality. His trajectory also led him to multiple incarcerations and eventually a padded detox cell where for the first time his father’s Buddhist practice, which he had previous dismissed as “hippie meditation bullshit,” took hold. He has been sober since 17. His path is chronicled in his classic first book, Dharma Punx.

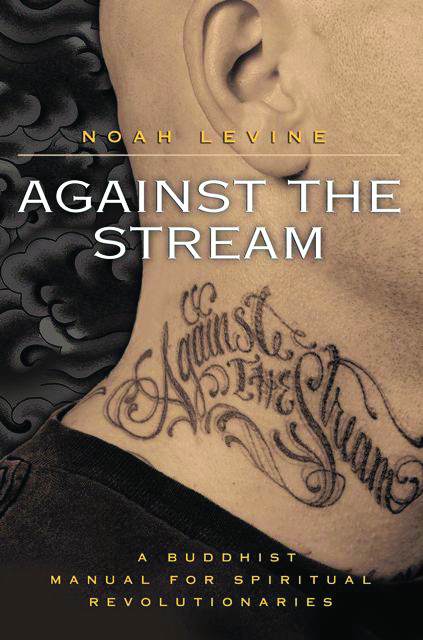

Levine has gone on to become a spiritual revolutionary who effectively blends Buddhism with psychotherapy and the punk philosophy of his own street experience. He is founder of a vast network of outreach programs including The Mind Body Awareness Program, Against The Stream, and Refuge Recovery, whose fundamental missions are to help all people—including at-risk youth and prison inmates—recover from addiction and help find freedom through the Buddhist-inspired path of awareness, forgiveness, and compassion.

Noah, who is the father of two, lost both his own father and his own marriage recently. We spoke on the day of the presidential inauguration on a vast number of topics pivoting on his experience of love.

Common Ground: Let’s start from the beginning. Where were you born? Who were your parents? What is your first memory?

Noah Levine: My parents met in Haight Ashbury in the sixties, and then they escaped to Garberville in Humboldt, where I was born. When I was one, my parents moved to Santa Cruz and divorced when I was about two. I have some vague memories of my parents together. My earliest memories are of feeling lonely and isolated and despondent. I’ve clear memories of a feeling of suicidality at about five years old and of wanting to escape from the suffering that I was already experiencing at a young age.

Why such thoughts so young?

The suicidality on some level was influenced by my father’s work with death and dying. The openness around death being a natural transition and an escape from a painful body that included a continued rebirth process. In my child mind I internalized, “Oh, death is a desirable escape when you’re in pain.”

Ouch. So was childhood just unhappy or mixed?

Mixed, but I would lean toward difficult and unhappy. By the time I was 6 years old, I was smoking cigarettes and pot. By the time I was 9 or 10, I was drinking alcohol and seeking escape. So I recall very pleasant experiences in my childhood, but my behavior points toward somebody who was really trying to get away from himself.

Can you talk about your intense trajectory with drugs?

When I was about 10, I started taking hallucinogens—mushrooms and LSD. I was smoking pot and drinking alcohol—regularly—by the time I was 11 or 12. I had that early suicidal feeling that lasted throughout my adolescence, and drugs and alcohol took the edge off. It was quite fun getting high and running around the beach in Santa Cruz and in the redwoods. By the time I was 12 or 13, I discovered punk rock shows. I heard the Sex Pistols and the Clash and Black Flag and those early punk bands. Punk rock’s aggressive critique of society and its pointing out the same suffering and oppression that I was clearly feeling—in combination with the drugs and alcohol—was a lot of fun in the early 1980s. I found an inclusive community in punk rock and drugs.

You see Buddhism and punk rock as both being founded on the noble truth of dissatisfaction, no?

Yeah. There’s a big common ground there. The Buddha started his teaching by acknowledging the unsatisfactory, the difficult, the painful, the tendency toward greed and hatred and delusion as being the powerful driving forces in this world. And that’s what punk rock is pointing to and expressing.

I don’t routinely associate psychedelics with the punk scene.

There was quite a bit of psychedelics in the punk scene. It was long-lasting and very cheap. You could take a $3 hit of acid in the eighties and be high for the whole day. Part of it was the economy of intoxication.

I’ve learned to think about drugs and any addiction along a spectrum where at the beginning, there’s fun. Fun is the original draw and why people are attracted, but as one moves toward the middle of the spectrum, the fun becomes equally mixed with problems. At the other end of the spectrum, the fun is gone, and it’s just a problem. Does that make sense? If so, when did it stop being fun?

That mostly makes sense, but to me even at the end, when there are so many problems and addiction is creating more suffering than it’s alleviating, there’s still the fleeting experiences of relief from the pain. That’s the repetitive cycle of addiction. For me it was pretty fun until somewhere in my mid-teens, when I was strung out on crack and shooting heroin and drinking alone, and it wasn’t a party. It was full-time addiction.

A path that landed you in jail. Can you describe what that was like? Didn’t you try hard to commit suicide in your cell?

I think [that at the time of] my first arrest, I was about 11 years old. Then in junior high school at 13, I was arrested several times. I ended up in juvenile hall over and over at 15, 16, 17. Each time, they started keeping me longer in juvenile hall until I was first incarcerated. I did have a suicide attempt, although I wouldn’t classify it as having tried very hard. Looking back, it was more of a pseudo suicide attempt or maybe a cry for help, although if I had the means to kill myself, I may have done it. I was incarcerated and started slamming my head against the cinderblock wall trying to crack my head open. I did end up on suicide watch in a padded room.

Wasn’t that about the time you went from repudiating your father’s meditation path to embracing it?

It was spring of 1988, at the end of my drug and alcohol years, and that suicide attempt where I essentially found myself in a place in my own mind—of desperation and hopelessness. Up till that point I had always blamed society and the system and the police and my parents and never taken any responsibility. When I woke up in that padded cell I realized, “Oh, I’m here because of my actions.” It was the first time I took some responsibility. I can be an anarchist and critique society and have some discerning wisdom about what’s wrong with our world, but that doesn’t excuse my actions and all of the hatred and craving that I’d let fuel my life. Nobody was forcing me. It was the turning point—recognizing that I landed myself there. It opened me to the possibility that I’m not a victim, and that I have agency in this, and that maybe there’s something I can do to change.

The shift from complete hopelessness to taking some responsibility gave me hope. I think my father sensed a shift was taking place and took the opportunity to offer me some simple instructions. I took his telephone call in prison, where he introduced me to Buddhist meditation. So I went back to my cell and started practicing mindfulness and breath. That was a real turning point.

Hadn’t you been exposed to those techniques all your life?

I witnessed it knowing that hippie spirituality was what my father and his friends were into, but I had completely rejected it as a waste of time. I had turned my life toward a violent resolution, not a meditative self-help path. So I was aware of spirituality but never had any interest to investigate until that desperation came.

For your father’s generation, psychedelics famously served as an inroad for people to open to spiritual insight, yet your early exposure to psychedelics was more nihilistic.

I was probably too young to assign spiritual insight to the hallucinations like older people who were having unordinary states of consciousness. I was too young to have any other context for it other than it being a pleasant escape. Even though what I was doing was quite scary, I was like, “This is cool, different, and fun, and this will get you fucked up all day for three bucks.”

You’ve been very critical of your father, and I wonder why. What was it like to be Stephen Levine’s son?

I’m surprised you say that I’ve been very critical because I don’t tend to be supercritical of him. I have a very mixed feeling toward my father, where I have a ton of gratitude and feel like he was a really important teacher for spirituality and death and dying and was actually one of my core teachers who saved my life by giving me those instructions at the right time. So while I have reverence for my father as a dharma teacher, I look at my life and think, “Why was I taking all those drugs and behaving in all those ways?” And I can see, “Oh, my parents weren’t so present, weren’t so attentive, and weren’t so tuned into what was actually going on with their children.” I feel so much love and appreciation of the teacher, and I land in a place of “his parenting style didn’t quite cut it.”

Wasn’t it “T Bone” Burnett who said something like “90% of all rock and roll songs are about musicians’ daddy issues—variations of “Wa-a-ah! Daddy, pay attention to me”?

[Chuckles] Right. Makes sense.

Your father passed away recently. How did that affect you?

Deep sadness, but it was a gradual process since he’d been sick for years. His life’s work was turning toward death and dying—and normalizing it. He prepared me for his turn and for everyone’s death with an attitude of acceptance of the natural process. And the natural grief of loss.

This being our Love issue, I want to get some of your reflections—specifically about parental love now that you have two children of your own.

[Chuckles] People say, “Oh, when you have children it changes everything and you experience love on a whole new level.“ Well, I have to admit I was a bit cocky when I was going to be a father, thinking, “I’ve been doing lovingkindness meditation and compassion and forgiveness, and learning to love myself and dedicating my life to love and service already for 20 years.” My attitude was, “Oh, that’s for people who have never really opened their heart before,” but having children definitely humbled me and my arrogance around it. There is another cellular, primal level of connection that I have with my children that no other relational love has ever touched. [Chuckles] It’s true. What they say is true.

Ah, yes—like the difference between reading a book about parenting or about love versus having direct experience.

It changed my relationship to my own parents, where I see that this really is difficult at times. I have more empathy. Then the reverse is, “Oh wait, this is so important. How could my parents have not been more present?”

I find myself channeling my own parents. Kinda scary, huh? [Chuckles] Have you ever felt that?

For sure. I see some of that looking at those inherited habits and parenting styles.

Can you describe the concept of metta in the Buddhist tradition?

Metta is the experience of unconditional kindness and love and friendliness toward all living beings and toward oneself. That experience came to the Buddha through practicing mindfulness and then became a teaching. The Buddha taught that the core causes of suffering for us human beings are clinging and craving, aversion and resentment, greed and self-centeredness, and delusion. Through his own present-time awareness practice and his effort to investigate his own mind, emotions, and temptations, he was able to free himself from the causes of suffering. He radically changed his relationship to both pleasure and pain by understanding their impermanence. He no longer attached to greed and pleasure and no longer met pain with aversion, fear, or hatred. After that liberation and awakening, what remained as his primary outlook was the experience of metta—unconditional kindness, love, and compassion.

Now, at some point the Buddha realized that mindfulness wasn’t working so quickly for some of his students, so he actually began to teach metta as a meditation practice. That is, you incline your heart and mind and direct them toward loving and kindness through a simple phrase: “May all beings be at ease.” This is a generous wish for the ease of all living beings and the core practice of metta.

Sometimes mindfulness gets a bad rap for being emotion-blunting in the way it emphasizes dispassion and equanimity. Any response to that?

Human beings can misuse anything [chuckles] and yes, meditative techniques could be used as avoidance techniques—or for blunting. But I believe the Buddha’s core instruction is that mindfulness is nonjudgmental awareness of what is, and that includes all of our emotions—inflictive emotions as well as joyous emotions. Equanimity is not an experience of being free from strong emotions but of not taking them so personal. The teaching is to respond skillfully to being in the experience of ease in the midst of whatever emotions are arising.

Metta compassion has become your fulltime job. Can you describe what you do to help at-risk youth?

A lot of my early practice was going into the different juvenile halls through a nonprofit organization we created called Mind And Body Awareness. At one point we had classes in almost all the juvie halls in the Bay Area (from Marin to Santa Cruz), teaching mindfulness and compassion to incarcerated youth. Of course, that came out of my experience, as that’s where I learned to meditate, so I wanted to bring meditative teachings back into those populations. After some years the organization was thriving, and I realized I can’t be as accountable to the incarcerated youth as I needed to be. It was time to turn it over to people who actually could show up every week.

I started traveling and teaching, and started an organization that was originally referred to as Dharma Punx but became Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society. For the last 15 years, my life shifted from juvenile halls and prisons toward being a dharma teacher for all who were interested. Jack Kornfield of the Spirit Rock Meditation Center trained me and empowered me in the lineage to become a Buddhist meditation teacher and move into teaching for the general public. A lot of that work started in San Francisco with my groups at the California Institute of Integral Studies and the Cultural Integral Fellowship on Fulton Street. Then we opened Against The Stream meditation centers in both SF and Los Angeles. It’s now an international Buddhist community with groups all around North America, Europe, and all around the world.

You started so many projects. Can you talk about Refuge Recovery? That is specifically around addiction, right?

Five years ago I realized that so many in my community were addicts in recovery and were using our Buddhist community (Against The Stream) as support for their addiction recovery. And while I too had come through the 12-step process, I never really felt it was the right fit for me. Buddhism felt the right philosophical fit because it was nontheistic, non-higher-power based. It taught about karma and purifying your karma and the take-full-responsibility approach rather than a theistic “God’s will” model. This just made more sense to me, so I started a Buddhist recovery model that I call Refuge Recovery. We run a treatment center as well as detox and residential and outpatient centers. We have close to 300 Refuge Recovery meetings all over the world. So yes, I’m very engaged in teaching and supporting addicts using the Buddhist path to heal from addiction.

Would you elaborate on the distinction between the Buddhist Refuge Recovery and 12-step, which is Christian-based, right?

It is, but we could be more expansive than just Christian and say it’s theistic. Any philosophy saying there’s an external power that has influence over you and that can bestow great accomplishment would be considered theistic. That includes Judeo, Islamic, Abrahamic but also Hindu theism. The 12 steps are certainly that. Its founders were primarily influenced by Christianity, but they were very open-minded and created 12 steps as open-minded theism, where its external power didn’t have to be Jesus or God of the Bible, but it did need to be a theistic higher power. Buddhism takes a different view on spiritual awakening—that nothing outside of you is going to give you grace or alleviate the causes of suffering. It says human beings have the full ability and capacity to end the causes of suffering through their own efforts—in this lifetime. I experience Buddhism and the nontheistic spiritual approach as much more empowering for one’s recovery.

I’m no expert, but my rudimentary understanding of 12-step is that one needs to hit bottom and there needs to be some surrender and some reckoning that this is bigger than me before grace—and real change—can come. Do you agree that bottoming out is a requirement for recovery?

Hard for me to say because I have my subjective experience where I hit my own bottom, but I was also very young. I was only 17 when I got sober and started my recovery path. I suffered quite a bit to get to that willingness, but you definitely hear stories of people that hit much deeper bottoms than I did. People talk about raising the bottom—that you don’t have to be a chronic alcoholic for 40 years in order to get into recovery. In my Buddhist community, people come who aren’t chronic addicts; they’re just seeking something else, and they don’t need extreme suffering to motivate them to turn toward spiritual awakening. I don’t think people have to go to the very depths. My father used to say—and I like this—that in order to make any big change in your life, you have to want something else more. You have to be sufficiently dissatisfied with what you’re getting to stop doing it. If drug use is satisfactory, you’re not going to stop. If greed or hatred is satisfying, you’re not going to want to stop greed or hatred. Some people need a real bottoming out, but for others it’s just saying, “Hey, this is nowhere. I don’t want to smoke pot every day. I want to be mindful. I want to be present. I want to experience joy and not just numbness.

Can you identify a common denominator amid at-risk youth?

There are so many different levels. There’s systematic racism and classism—that is the substratum of our society. The majority of youth that are locked up are people of color, and that trauma gets handed down from generation to generation. Then you also see the middle-class or upper-middle-class and wealthy youth that are at-risk because of the lack of love and appropriate attention that is given in their families. Youth learn their behaviors from their environment, whether it’s racist or enabling or some dysfunction from the home. Every single youth is playing out some kind of learned behavior and often some sort of trauma.

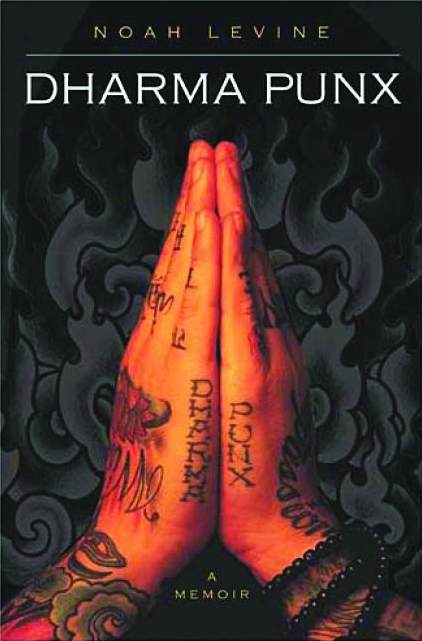

Your first book, Dharma Punx, made you famous. Can you summarize what it’s about and what effect fame has had on you?

It’s my memoir of spiritual adventure and a lot of what we’ve been talking about: my path of rebellion and addiction while growing up in the second wave of punk rock and my turn to recovery and the Buddhist practices. It’s about the common ground between why I loved punk rock so much and why Buddhism made sense to me and my becoming a teacher trying to help disaffected and dissatisfied subcultures of people who are looking for a spiritual awakening.

I want to congratulate you because I know people firsthand whose lives were improved by reading the book. My God, even if you can help one person, that’s a life’s work right there.

That’s the core intention—to help and give some hope and say, “Hey, if this fucked-up punk rock kid can do it, maybe I can too.” I was reminded just this week when somebody who works with street kids, mostly addicts, contacted me to say he started giving Dharma Punx to teenagers he was working with who were living on the streets. He said they were reading it, and although they weren’t necessarily stopping doing drugs—they were still “in the life”—a bunch of them started getting Dharma Punx tattoos. He asked the kids about the tattoos, and they admitted that they weren’t crime- and drug-free—yet—but they said, “It gives us something to work toward.” So that was beautiful to hear—that 15 years later the book is still making the rounds with kids in the situation I was in. The tattoos inspired them to become a community and recognize that their intentions were greater than staying stuck.

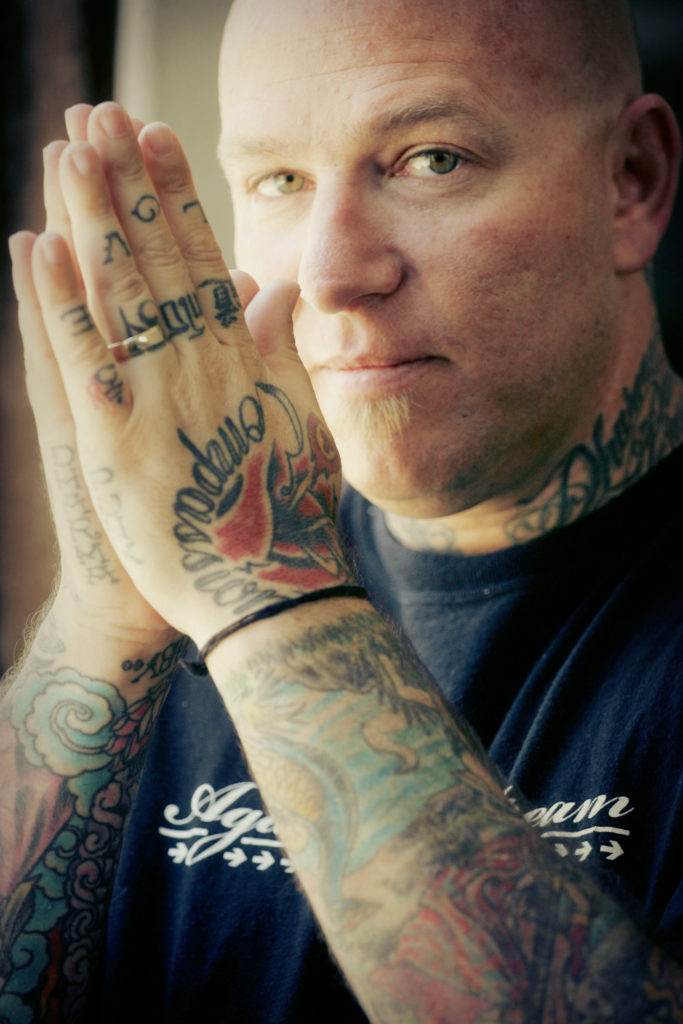

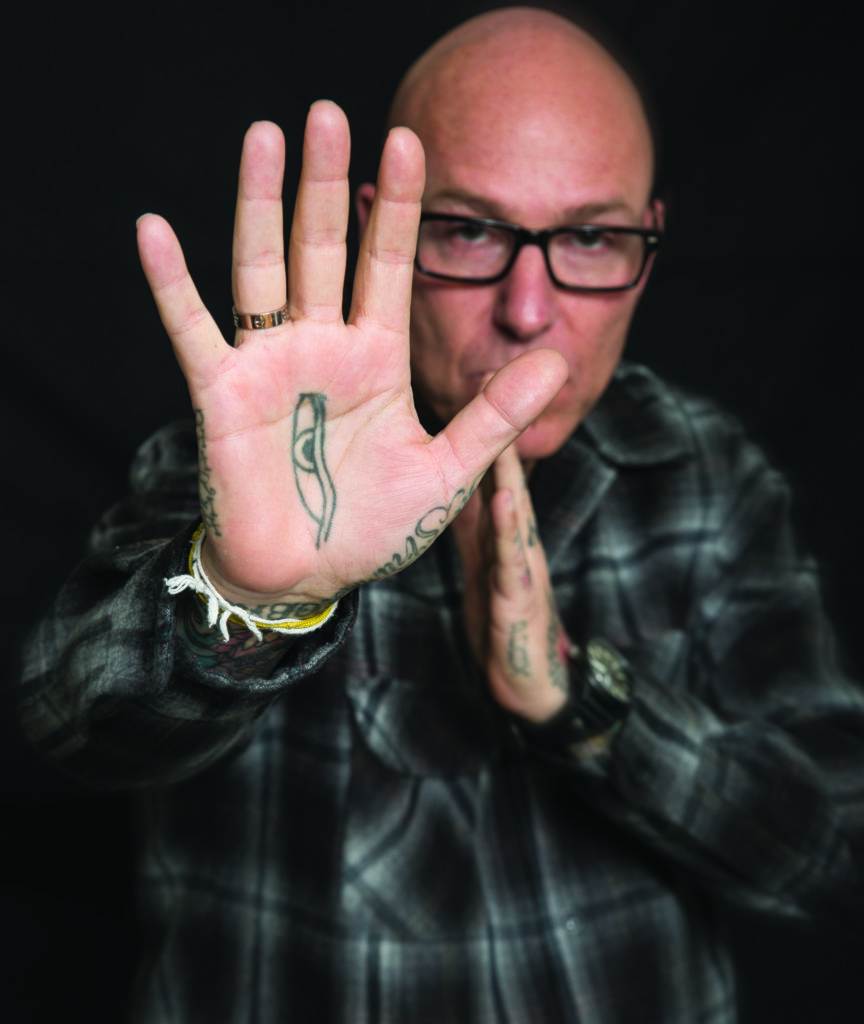

Let’s talk about tattoos. You’re covered.

[Chuckles] Okay, but you know I dodged the question about fame.

Oh yeah, fame. Then we’ll go back to tattoos.

Yes, I am glad and grateful for the success and attention I’ve gotten, but thankfully the meditation I am teaching is constantly reminding me to not take it too personal—to not cling to it and to not need it and to not be too identified with it. I’ve seen friends that have gotten famous from being artists or musicians in a more material way that’s compelling them to take it personal. Now, I certainly have an ego, and I wouldn’t say that my ego doesn’t have an inflation or a deflation, like when I get a bad book review or some criticism. But I also have a deep mindfulness practice that helps me not suffer so much around the praise and blame of being a public figure.

So what is the significance of your tattoos?

I started getting heavily tattooed to belong to a subculture of people who were setting themselves apart. It was a way to say “we have the freedom to decorate our bodies, and we’re not playing by the rules of the mainstream.” Being heavily tattooed meant “we’re not going to have this kind of job or that kind of job.” Now the whole tattooing world has changed, with reality television and professional sports. It isn’t as radical as it used to be. Most of my tattoos are of spiritual Buddhist images that remind me of my intentions and my ethics.

Are you still attracted to punk rock?

Yes, I still listen to punk rock on a daily basis. Not only is it the music of my youth and the voice of my generation, but especially with the current political situation, it’s a fierce, compassionate critique of this world. Punk rock is more relevant than ever.

I grew up listening to punk, but since we’re talking about the heart I gotta say that as I mature, I lean more into softer, heartfelt stuff [chuckles]—like Neil Young. Not you?

I don’t have the full answer to this, but what seems true for me is I don’t go to music for soothing or relaxing or the kind, loving vibes. Music holds a place in my life which is more celebratory or kind of fierce. That said, I primarily listen to three kinds of music: punk rock, rap, and Jamaican music—all the way from early Jamaican ska and northern soul to traditional roots reggae. So the reggae has a more chilled-out tone and maybe even some loving qualities, but I don’t tend to use music for that. I actually rest in that kind of loving vibration in my mediation or in my general attitude of kindness toward people.

What constitutes music to make love to?

I know that’s a popular thing to do, but I almost never listen to music for lovemaking. I wouldn’t want the distraction from the meditation practice that sex is.

Sounds like being a good meditator would make you an obvious Tantra man. Isn’t that the endgame of the Tantra premise—presence, mindfulness, not being distracted?

Yeah, I have some familiarity with the ancient Hindu roots of Tantra and some of the ways Tibetan Buddhist Tantra is taught, but I’m not so familiar with Tantra in the modern Western kind of workshop model and wouldn’t even use the term. I just call it mindfulness, or just being present with what you’re doing—whether you’re walking down the street or making love.

Who are your punk heroes?

For some reason my personality is such that I look back at the originators as my core heroes and influence. So I’m interested in the Buddha, who is the originator. There have been so many great punks who really created this thing: Joey Ramone [the Ramones], Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious [the Sex Pistols], Joe Strummer and Mick Jones [the Clash].

Who are other main influences?

[Chuckles] You mean other than Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious, Joe Strummer? Ah, you mean actual meditator guys like Jack Kornfield and Ajahn Amaro. Well, there’s also Jack Kornfield’s teacher, Ajahn Cha, of the Thai Forest tradition. These have been the biggest influences but also my father and Ram Dass. From the Hindu tradition there’s Ramana Maharshi and Nisargadatta Maharaj. The Dalai Lama is an influence, as is Suzuki Roshi from the San Francisco Zen Center. Thich Nhat Hahn. So I have a lot of different influences, though my core teacher has been Jack Kornfield of Spirit Rock and Ajahn Amaro, who used to be coabbot of the Abhayagiri Monastery in the Yukon but is now in England at the Amaravati Monastery.

What influences from the psychology field?

I do have a master’s in psychology from California Institute of Integral Studies, so the humanist psychologists are an influence. [Donald] Winnicott, [Carl] Rogers, the Gestalt of Fritz Perls. I’ve become interested in the attachment theories of John Bowlby. And even though I have some critical views of the 12 steps, I was very supported by that, so I count Bill Wilson and Bob Smith, the founders, as part of my influence and lineage.

What make you happy and, conversely, what pisses you off?

My greatest sources of joy come from quality connections with family and friends and being with my children. I love laughing, so I like to tease and joke. I get frustrated with the corruption, oppression, and ignorance that is pervasive in our racist, sexist, homophobic society, but it doesn’t piss me off. I rarely go to real anger anymore. Mostly I come back to feeling the pain and meeting it with compassion.

I feel that punk rock taps into anger and nihilism like nothing else.

For me punk rock isn’t so much about anger as much as it is an outlet and celebration of healthy aggressive tendencies. Like testosterone—what do we do with it? Okay, let’s scream about it without causing harm to anyone else. Some punk rock is nihilistic, but if you listen a lot you’ll find positive, engaged, political social messages about hope and solutions. Just like the Buddhist’s first noble truth of pointing out the suffering—it’s a critique that can end in nihilism, but quite a bit comes to talking about problems with “What are we doing about it?” It can be very engaged and even compassionate if you listen carefully.

What do you grapple with personally on your spiritual path?

Every New Year I do a period of reflection and setting intentions. This year, post-divorce, post my father’s death, and being a middle-aged man, I feel that the growing edge for me—and this is appropriate to your theme—is love and intimacy. Rather than always being the guy in the front of the room teaching about love and service, which I really enjoy, I feel that a long-term committed relationship on a deeper level, with accountability and intimacy, feels like the next growing edge for me.

Can you share how your divorce affected your heart?

My marriage ended about a year and a half ago, and there was sadness and grief and concern as to how the impermanence of our relationship would affect our children in the transition. The whole “I’m going to be with this person for the rest of my life” thing is such a beautiful intention but also a romantic and unrealistic delusion. Relationships don’t last forever, as we know from divorce rates. My ex-wife used to remind me that on our very first date, I said some things to her about the impermanent nature of the world and that we were signing up for some loss because even “happily ever after” still meant that one of us would die first.

Now, there were some difficult circumstances around the end of our marriage, with feelings of betrayal and dishonesty and things that went on, but I was able to turn love, compassion, and forgiveness toward the pain I and my ex-wife and our children were feeling. Ours had a natural ending with a commitment to being good co-parents. I am grateful to have a mature adult divorce with 25 years of meditation practice to draw on.

People double down to keep a marriage together for the sake of the kids.

Honestly, I probably stayed a couple of years longer than I would have if we didn’t have children.

Do you have any final reflections on love?

The one place our conversation hasn’t gone that has been important to reflect is that love is more of an experience of generosity. In true love there is no attachment, no clinging, no needing, but only a desire to give. The near enemy of true love is sentimentality, with attachment, clinging, and craving. As soon as we step into that attachment we’re no longer in love.

Okay, relationships cannot be unconditional. [Chuckles] Right? There are certain conditions that need to be met in relationships or they’re not healthy and viable. We’re not loving ourselves when we stay in unhealthy relationships. But love itself is an act of giving. The ideal of relational love has both giving and receiving, where love is neutral—neither demanded nor needed, but freely offered.

You’ve come so far from the kind of self-hatred that once led you to want to snuff it, but I don’t see shame or self-hatred in you. It seems you’ve got your shit together.

Very little shame or self-hatred, which I attribute to a kindness and compassionate meditative transformation that happened after the first decade of becoming sober at 17. My shadow is more on the side of arrogance or privileged entitlement rather than shame. One of my good friends, Vinny, who is the guiding teacher of the San Francisco Against The Stream Center on Folsom jokingly said to me, “Dude, you could use a bit of shame.” Some would say that shame is actually a healthy emotion at times. I could use a helping of humble pie without beating myself up too much, but yes, I do have a lot of confidence and hope and not a lot of fear. It wasn’t always this way, like when I was trying to kill myself 30 years ago.

Do you ever feel misunderstood?

Not much, but sometimes in the mainstream Buddhist world, I face challenges based on my appearance and my attitude or my language—the fact that I swear quite a bit while teaching gets me some pushback from some of the more conservative voices within our Buddhist communities.

Speaking of conservative, as we speak Donald Trump is being inaugurated. How do you feel about our new president?

There’s still a sense of surprise. You know, I thought it was a joke. The fact that it’s reality gives a sense of fear and concern. It’s sad and painful to see somebody who seems very confused about human beings and about equality and kindness and compassion. From the Buddhist punk rock perspective, it’s not big news—that ignorance wins again and that corrupt politicians run our countries. It’s the always-has-been-always-will-be thing, but after Obama I think people were lulled into thinking, “We’ve made progress.” The transition from Obama to Trump feels like one step forward and three steps backward, but let’s continue to work for positive change. It will come from love and compassion and forgiveness—not hatred.

It’s amazing how far the heart can expand, huh? You’ve come a million miles, but do you ever get a glimpse of how far love can go?

I definitely do. And I don’t feel like it’s personal to Noah Levine. I’m not special. Anybody can have this experience that does the work, right? This is what all human beings experience when they turn inward and learn to love and forgive themselves. When we turn our attention toward our own hearts, love and compassion are revealed. This is just human nature.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.